The Leftist delusion of a world without danger

Thomas Hobbs, who was born into the waning years of the 16th Century and lived three-quarters of the way through the 17th Century, in his great work, Leviathan, characterized man’s life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” He was not an optimist.

Hobbs may have been a pessimist, but he was also quite accurate. In a pre-industrial, pre-scientific era, half of the children lucky enough to survive childbirth would die before their fifth birthday, with death usually resulting either from disease or accident (falling into an open fireplace or drowning in a well or waterhole were accidents common to the pre-modern era).

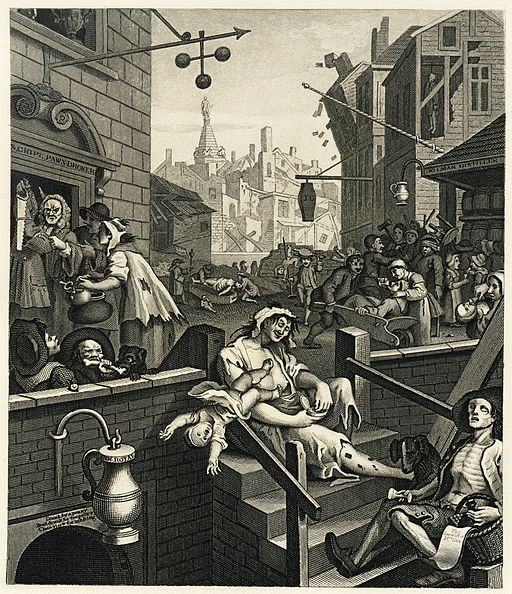

If one was lucky enough to survive early childhood, life still didn’t get much easier. Even in stable communities, food supplies were unreliable; crime was prevalent; war had a nasty habit of breaking out all over; disease stalked everyone; childbirth was the scourge of young women; lightning and cooking caused deadly fires that swept through wood-built communities; and weather forecasts were nonexistent and weather deaths (cold, heat, lightening, floods, winds, etc.) were commonplace. Old age was a rarity — or at the very least, was defined differently, with a toothless crone in her late 40s qualifying as “old.”

For those who managed to avoid premature death, life was dark indeed. I mean that literally. Except for the very rich, who could enj0y beeswax, the poor lit their homes (which usually had no windows) with smoky fires or tallow lights that left everything smelling like an old fryer at McDonalds.

Personal cleanliness was viewed with suspicion (as a sign of moral debauchery) so it wasn’t uncommon for people to go a lifetime without bathing. Nor was this filth limited to the lower classes who had no access to running water. James I of England was famous for his certainty that bathing would kill him. Even the marginally clean English found his personal habits distasteful. Streets and sewers were interchangeable, with people in buildings tossing the contents of their chamber pots into the streets, regardless of passing pedestrians.

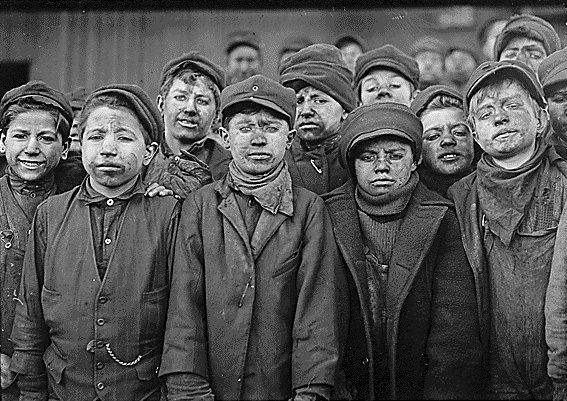

The Hobbesian world began to change with the industrial revolution. Wealth was no longer tied to the land and, therefore, finite. It was suddenly infinite. Although the initial transition from agricultural to industrial wrought appalling havoc for the poor, by chaining them to factory labor or coal mines in conditions that were little better than slavery, working their children to death, and herding them into filthy urban ghettos, overall the standard of living rose for everyone. The rich, of course, benefited first, but the poor did too, to the point at which (at least before the endless Obama recession) even the poorest in American (unless they were insane homeless people) were able to buy cool shoes and disposable cell phones at Walmart. Poverty became a matter of discomfort, not death.

Things became even better when the scientific revolution picked up steam. Suddenly, scientists and physicians had the comforting illusion that, when it come to the mysteries of disease, they could see all and know all. Bacteria were visible and, with Penicillin, vulnerable. Ailments originating within the body (a hot appendix, a bladder stone, even a damaged heart valve) could be fixed. Viruses bowed down before vaccinations. We were going to live forever. Indeed, even though we 21st century residents haven’t actually achieved immortality, our modern lifespans would have been unimaginable only a century ago.

One of the most stunning byproducts of the industrial and scientific ages was childhood, not just as a biological reality, but as an intellectual construct. Past times recognized infancy and early childhood (until about 7 years old) as times of necessary development and dependency. After that, though, right up until the Victorian age, children older than 7 or 10 years were regarded as mini-adults. They were put to work in field or factory, indentured to trade, married in their mid-teens, and generally given responsibilities that, nowadays, we still consider too extreme even for “children” in their mid-20s. Even twenty years ago, people would have laughed at the thought that “children” of 26 were dependents for insurance purposes. Go back a time a few more decades than that, and the rules were simple: if you survived childhood, you headed rapidly into adulthood.

These very positive historical trends have left us with one very wrongheaded delusion: the belief that we can insulate ourselves and, especially, our children from all danger.

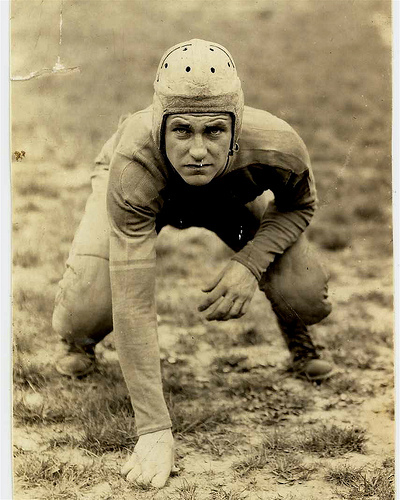

Sometimes, the very act of insulation creates greater, counter-intuitive risks. Those of us who don’t remember football being so dangerous in decades past are right. It’s not just that we were less aware of the risks, it’s that football players had less protective gear. It was a speed and passing game, one that favored smaller players and less aggressive contact. Leather helmets provided some protection, but did not encourage players to pretend that they were big horn sheep who could engage in serious headbutting. Once players became enswathed in protective gear — high-tech helmets and shoulder pads — they began to play a more aggressive game, one that favored big players and high impact tackles. In other words, the counter-intuitive result of more protective gear in football is a higher, rather than a lower injury rate.

The same is true in the boxing world. When boxers were bare handed, they couldn’t land a hit harder than their own knuckles would bear. As between a solid jaw bone and a knuckle bone, the jaw usually won. Even with the advent of gloves, the early gloves were thin enough that the striker still had a risk about equal to that of the person on the receiving end. It was only when the boxing world shifted to massively padded gloves, which successfully insulate the knuckles, that boxers were able to land such devastating strikes against their opponents’ jaws, eye sockets, and temples.

We’ve also over-protected ourselves is in the battle between antibiotics and bacteria. After a seventy year run in the antibiotics’ favor, the bacteria have regrouped and are coming back strong. One regularly reads upsetting stories about treatment-resistant bacteria. Tuberculosis has the potential to become a scourge again; MRSA haunts hospital hallways; and many of us our digging out our grandmothers’ household hint books to find out how people treated garden-variety infections (cuts and ear aches) in the era before antibiotics came along. In the same way, we’re facing the ugly truth that, due to a combination of parents resisting vaccination, and diseases resisting vaccination, old childhood scourges such as chicken pox, whooping cough, and measles are on the upswing.

We can’t win for losing. Or rather, we have become so confident of our victories that we forget that the enemy — even one that lacks cognitive abilities — is as intent upon its own survival and is as adaptable as we are.

The above are, in a way, mechanical protective reflexes, where industrialism and science enable us to place barriers between us and objects or pathogens that are dangerous. What is a peculiarly Leftist foible is believing that we can ignore entirely Nature writ large, human nature, or cultural pathology.

Going back to the topic of childhood mortality, the sad fact is that, while kids once fell prey to disease, they now fall prey to all sorts of other things, some new and some old. Here’s a 2007 snapshot of the things that killed American children who survived congenital diseases in infancy:

Car accidents: 6,683 deaths

Firearm homicide: 2,186 deaths

Suffocation/strangling: 1,263 deaths

Non-firearm homicides: 1,159

Drowning: 1,045 deaths

Poisoning: 927 deaths

Suffocation suicide: 739 deaths

Firearm suicide: 683 deaths

Fires/Burns: 544 deaths

Firearm accidents: 138 deaths

Poisoning suicide: 133 deaths

What may leap out at you is how many children died in 2007. What leaps out to me, since I’ve always bathed my brain in history, is how few children died in 2007. Although each of the above numbers represents indescribable grief, the percentage of child deaths is infinitesimal compared to the overall population of children in America. Moreover, by far the largest number of deaths occurred in a peculiarly utilitarian way: car accidents. These were unintentional deaths that resulted from an object that is integral to our society’s functioning.

The next highest number of deaths, as any Progressive would point out, is indeed from guns. But here’s what the white liberals ignore until there’s a Columbine or Sandy Hook that makes them feel vulnerable In that same year (2007) that 3,345 American children were murdered, here are the statistics for male youth deaths within the black community:

52.3% of black, male 15-19 year olds who died were murdered.

15.5% of black, male 10-14 year olds who died were murdered.

6.3% of black, male 5-9 year olds who died were murdered.

14.3% of black, male 1-4 year olds who died were murdered.

The situation is better, but not much, for black girls in 2007, as they are less likely to die as teens, but more likely to die as toddlers:

18.3% of black, female 15-19 year olds who died were murdered.

9.3% of black, female 10-14 year olds who died were murdered.

6.5% of black, female 5-9 year olds who died were murdered.

15.3% of black, female 1-4 year olds who died were murdered.

In other words, we don’t have a gun problem: we have a black-children-are-getting-murdered problem. Those liberals who pay any attention at all to deaths that don’t involve white suburban children, never bothered looking at human nature in order to determine how to deal with the problem.

They didn’t look at the way welfare renders stable, earning males obsolete, thereby breaking down the family unit and forcing young men to find other ways than family and maturity to prove their “manliness.” They didn’t consider that if you attack Judeo-Christian morality without providing an alternative morality, you end up with no morality. They didn’t consider that advancing abortion in all-black communities is a subliminal message that black lives are disposable. Instead, they ignored the human factor entirely and decided that, if they made weapons illegal, the communities would instantly become hippie-like communes of peace, with a little pot on the side.

Because Progressives thought they could bring a mechanical solution to a human problem, even more black children died. Think of it this way: Getting rid of bacteria doesn’t make them go away. They come back stronger in different ways. Likewise, getting rid of guns doesn’t make murder vanish. Humans get creative with other forms of murder, and guns go underground and, removed from law and morality, get applied in ever more violent ways.

We cannot protect ourselves into safety. The world is a dangerous place, albeit infinitely less dangerous than it has ever before been. We are deluding ourselves if we believe that, either through hyper-safety mechanisms or bans (bans on bacteria or bans on guns) we can instantly make things safer. In fact, it’s often the case that eradicating the danger entirely is either a delusion (bacteria are still out there) or creates worse dangers than that we originally sought to avoid.

What we can do is try to modify certain behaviors in order to decrease (although never eliminate) risk. If antibiotics are becoming less useful, let’s wash our hands more often. If violence is plaguing a community, let’s try to temper the community by giving people constructive purposes in life and by creating a sensibility that values life. Getting rid of guns will not get rid of violence. Valuing life might just diminish it somewhat, though.