Barack Obama’a America: Keynesian economics on steroids

When I was in junior high school, high school, and college, my American history classes always preached the same message: Franklin Roosevelt saved America by “priming the pump.” That is, he took money away from the rich, filtered it through the government, and then used the brain-power built into government to decide upon the infrastructure projects we know and love today, everything from Hoover Dam, to the Tennessee Valley Authority, to the cool art deco post offices dotted around the nation. It was only when I was in college that the teachers put a name to this wondrous system: Keynesian economics.

Keynes wasn’t a communist. He just wasn’t a believer in marketplace efficiency. He advocated a privately-owned economy, with the government making the important decisions. (The Nazis, incidentally, used this economic approach, which they called “National Socialism.”) More than that, Keynes and his acolytes believed that, when times were tough, the only entity that could respond rationally and effectively to market chaos was the government. Keynesians therefore believed that economic downturns should be met with higher taxes from the rich and more government spending directed at the poor. The theory was that the poor would take this money and pour it back into the economy, thereby priming the pump.

Apparently Keynes and his friends had never read Frédéric Bastiat’s “broken window parable” or, if they had, they dismissed it as a foolishly simplistic parable that wouldn’t meet the demands of the Ivory Tower and elite governance:

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James Goodfellow, when his careless son has happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation—”It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?”

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier’s trade—that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs—I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, “Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.”

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

But back to history as I learned it.

After their almost rote teaching about Roosevelt’s brilliant Keynesian save of the economy, my instructors would always add, sort of as an addendum that wasn’t really important, that WWII finally broke the Depression’s back.

War does represent the perfect Keynesian paradigm, with the government directing the whole private-sector economy towards a single martial goal. Putting aside the twenty million dead, war was good for the Soviets too. And right up until D-Day, the Germans weren’t doing so badly with a war economy either.

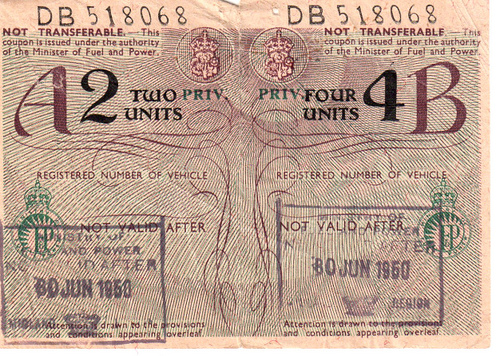

As the British discovered, though, once war is over, continuing a war-time economy (complete with government rationing) doesn’t work. The government may be good when everyone’s efforts are directed to national survival, but it’s a lousy wealth creator during peace time. Only when rationing ended in the 1960s did the British economy start to recover, and its real boom happened after Maggie Thatcher de-nationalized major industries.

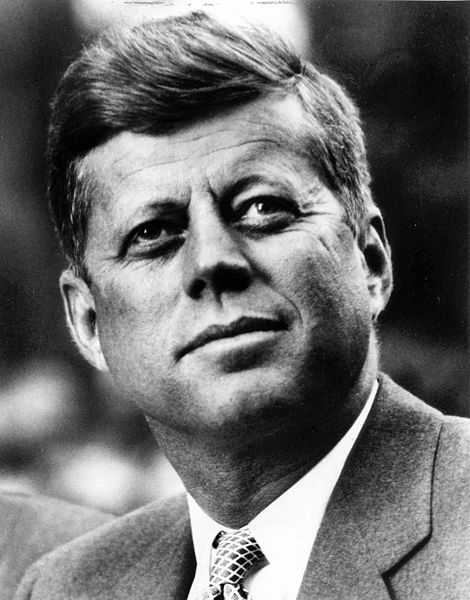

In America, the post-War period was the anti-Keynesian period, and that — not Roosevelt’s taxing and spending — is what really broke the Depression’s back. The late 40s and the 1950s celebrated American individualism, innovation, capitalism, and freedom. With Communism as a foil, America was almost aggressively free. And when it periodically tried to put the brakes on that freedom by raising taxes, the market foundered. John F. Kennedy got it:

“In today’s economy, fiscal prudence and responsibility call for tax reduction even if it temporarily enlarges the federal deficit – why reducing taxes is the best way open to us to increase revenues.” — John F. Kennedy, Jan. 21, 1963, annual message to the Congress: “The Economic Report Of The President”

Although Kennedy did get his lower taxes, pressure from the Left resulted in another Keynesian experiment in the 1970s. The economy cratered. Reagan released the economy from tax pressure and it was revitalized. Bush Sr. (“Read my lips: no new taxes”) raised taxes again, and down the economy went. Clinton, under pressure from Republicans, decreased spending, which helped the economy grow again. Bush Jr. went one step further and lowered taxes, and the economy roared again — and that was true despite 9/11 and a long war.

Meanwhile, though, the Democrat controlled Congress that Bush got in 2006, while it didn’t address taxes, starting putting the government thumb on the scale again. Rather than backing off of banks (as McCain and Bush suggested), it increasingly limited what they could and couldn’t do. This government pressure resulted in banks being forced to give loans to people with no equity. The banks got creative to avoid risk, packaged, and resold these loans. It looked good for a while, and then, in 2008, the bubble burst.

Enter Barack Obama. Obama spent the first half of his presidency doing classic Keynesian pump priming by pouring massive amounts of government money into his pal’s pet projects. Many of those projects went bankrupt, others ran over cost, others never got off the ground. Obama also laid the foundation for an ostensibly private, but still government-controlled medical sector (1/6 of the American economy). The economy alternately stagnated or sagged. Romney fully understood the problem, but was never able to articulate the solution. Since he couldn’t sell the public on the free market (not to mention that he was trying to push back against the appalling character attacks leveled against him), the public in 2012 chose the devil it knew: Obama.

Obama has now begun the second half of his presidency by doing Keynes on steroids: on New Year’s Day, he got significant tax increases on producers, without in any way stopping his spending. Obama, though, has done something Keynes never imagined. Obama has not used the pump priming money to put shovels (or even spoons) in the hands of those who are supposed to reinvigorate the economy. Doing that at least gives those receiving government money a job (which is good for the resume and a sense of self-worth) and it gives them an ownership interest by allowing them to create a lasting benefit to society. What Obama is doing is just handing out money in the form of pure welfare. He’s not creating a working class; he’s creating a parasite class.

Classic Keynesian economics has never worked. Obama is now trying the un-classic version. If I were a betting woman, I’d say that, not only will Obama’s experiment fail, it will fail on a much vaster level even than Roosevelt’s Keynesian debacle. (And if you want to know just how bad Roosevelt’s failure was — and how grossly misleading my public school history education was — you must read Amity Shlaes’ The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression. Roosevelt’s economic experiments were a disaster, and it was only through the aggressive propaganda flowing out of Hollywood, media, and educational institutions, propaganda that escalated after WWII, that we remember his presidency as an economic success.)