Richard III’s remains positively identified

“Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this son of York,” says the malevolent Richard III in Shakespeare’s eponymous play. Generations of Shakespearean actors have portrayed him is a sinister hunchback, greedily eying his brother’s throne and eventually murdering two young boys in order to obtain it. The play was a perfect example of the victor’s ability to write history.

For centuries, people accepted Shakespeare’s portrayal at face value. Starting in the late 19th century, though, contrarion historians started challenging this view. They claimed that Richard III was a reasonable, temperate monarch, and that Henry VII was an overreaching usurper who needed to blacken Richard’s name in order to hold onto the throne that he had won by war, not by right. The problem for these revisionists always remained those missing boys in the Tower of London. Did they die? Did Richard murder them? Did Henry VII murder them? Who knows.

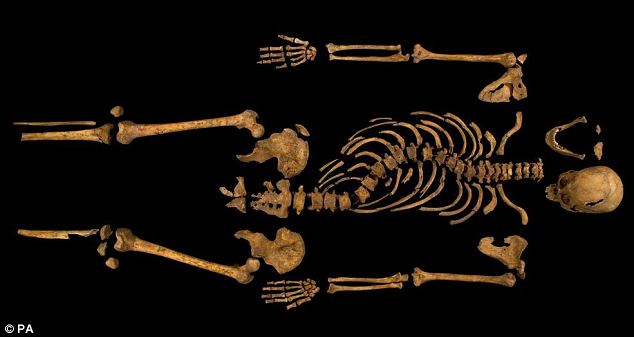

What we do know is that Shakespeare was right about one thing: Richard was indeed a hunchback. Thanks to a stunning example of historic investigation, coupled with modern forensic science, we can look at Richard’s skeleton — and he had significant scoliosis:

We also know now that he fought ferociously in the Battle of Bosworth, for his skeleton reveals ten significant cuts, three of which were on his skull, with each of those three having the right to be called a death blow. There are also indications that Henry’s soldiers engaged in a little body mutilation after he did. Richard did not go gently into the night.

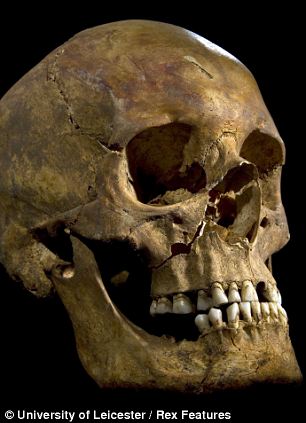

What struck me about the skeleton, in addition to the scoliosis and cuts, was Richard’s teeth. They’re beautiful. I didn’t expect the late-medieval corpse of a 32-year-old man to have such straight, white teeth:

Whenever I think of medieval smiles, I think of a mouth opening to reveal gaping holes and blackened stubs. Richard’s smile, though, must have been lovely: big and white.

The media claims that this skeleton will allow a wholesale reevaluation of Richard’s reign. My imagination is failing me, though, because I don’t know how a skeleton can reveal whether he usurped the throne, whether he was a good administrator for the two years he held it, or whether he murdered his nephews. It can tell us about diet and health, certainly, but the only historic fact it seems to prove is that he was a hunchback. Whether he was a good or a bad hunchback is something to discern from the documentary record, not the bones.