Thinking about the autism spectrum — and what you can do — might make you feel more hopeful

The news can easily make one feel terribly hopeless. The world is boiling, and we seem to lack direction.

The news can easily make one feel terribly hopeless. The world is boiling, and we seem to lack direction.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that America has been in the past a very resilient nation; that there’s sometimes a virtue to shaking things up simply because change is inevitable, so let’s get it all over with at once; that people at home and abroad are beginning to appreciate that America was never an Evil Empire, but was always a force for freedom and stability; and that ordinary Americans are seeing what socialist policy — economic, international, and societal — looks like, and they’re not pleased with what they see.

Here’s the other good news: There is always hope. Otherwise, why bother? Without hope, why bother reading the news? Why bother writing about the things we want to change? Why bother thinking, voting, talking, working, or even getting up in the morning? Things can and do change, and we who are hopeful have a responsibility to do whatever we can — to contribute whatever skill we have — to fulfill that hope by changing the political and social dynamic.

Since 2008, hope has been an overused and misused word. To begin with, it’s not a thing in and of itself. Only very shallow people believe that you can elect something called “hope.” Instead, “hope” is a very special human emotion that motivates us to leap over seemingly insurmountable barriers and face off against despair, all the while embracing behaviors that lead to increased individual and national freedom, self-reliance, and prosperity.

And while I’m on the subject of hope — real hope, not the politically-packaged pabulum — I’d like to take a moment to talk about families dealing with relatives who fall within the autism spectrum. Ido Kedar is one of those people. I’ve known Ido for a long time, although not as well as I could wish. Mother Nature gave Ido what appears to be a raw deal: His autism leaves his maturing brain in a body that responds to his wishes only with the greatest effort. He’s almost non-verbal, impulse control is an issue, his spatial awareness is limited, and coordination is a problem. On the plus side, though, he is endowed with a brilliant brain; a strong moral compass; hypersensitive senses, which means that, even though he can be easily overwhelmed, he sees, hears, tastes, smells, and touches a world of beauty denied to the rest of us; and a fierce drive to connect with the world which has enabled him overcome so many of his deficits.

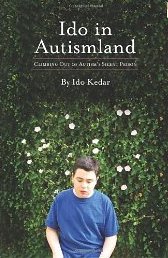

If you read Ido’s autobiography, Ido in Autismland: Climbing Out of Autism’s Silent Prison, you see that he isn’t just the physical embodiment of the abstract word “hope.” He doesn’t introduce himself to you by saying, “You can call me Hope.” Ido is, instead, a person whose parents never lost faith in him and a person who always had faith in his own abilities. That faith gave them the emotion that is hope, and that emotion in turn gave them the energy to search, research, act, practice, and excel.

Ido is not unique. There are many other young people (and their families) in the autism spectrum who never give up. They take their belief in future possibilities and turn that into present action. One of the institutions that actively helps them with this (instead of just mouthing “hope”) is the Friendship Circle . . . which is having a fundraiser Bike Raffle. If you know someone with autism, or someone who lives with or cares for an autistic person, and you feel like contributing to the cause, this is certainly a nice way to do it.

For more information, check out Raising Asperger’s Kids.