Movie Review: Cinderella

A word of advice if you go to see Disney’s new, live-action Cinderella: Don’t take a cynic with you. Cynics will not appreciate this sugary, beautiful confection. To them, it’s an offense at every level.

A word of advice if you go to see Disney’s new, live-action Cinderella: Don’t take a cynic with you. Cynics will not appreciate this sugary, beautiful confection. To them, it’s an offense at every level.

You’ll note that I said “sugary,” rather than the more dismissive “saccharine.” Something that’s saccharine isn’t really sweet; it’s fake. Disney’s Cinderella is sweet through and through.

Kenneth Branagh directed the movie with a mid-19th century sincerity that is utterly alien to movies that are directed at today’s youth market. There was no snark, there was no sleaze, there was no vulgarity. It was innocent and sweet and flowery from top to bottom. The little girl in the row behind me, maybe ten years old, loved it. So did I. The teenaged cynic in the seat next to me sneered the whole way through.

Although live action, the movie is a very respectful homage to Disney’s original animated Cinderella, which was released back in 1950, during a time that was also a less cynical than today — especially when it came to teenagers. This means that, when it comes to movie plot, if you’ve seen the original Cinderella, you’ve seen the new one too, which is open about its inspiration from both the 1950 movie and Charles Perrault’s fairy tales.

The changes Branagh makes are subtle. He has Cinderella and the Prince meet in a forest before the ball, when she does the PC thing and protects a stag from the Prince’s hunting party. This meeting is obviously meant to address the age-old complaint that the whole “you will meet a stranger across a crowded room” meet-cute is bunk. These two first meet across a pretty forest, so they are primed for love by the time the ball hit.

Branagh also tries to explain away the inexplicable, which is why Cinderella allows herself to be turned into a family slave when her father dies. She’s obviously an accomplished young woman, so it makes no sense for her to suffer as she does. In Perrault’s late-17th century milieu, of course, penniless, orphaned young women in remote chateaus, unless they had family to look after them, had no options. Or more accurately, they had no options if they didn’t want to be prostitutes.

Gail Carson Levine, in her delightful Ella Enchanted circumvented the problem of Ella’s very un-modern passivity by having her be the victim of a spell that made her incapable of disobeying a direct order. The book therefore became a very nice meditation about the nature of free will.

Branagh, in thrall to both the original Disney movie and the Perrault tale, didn’t have the luxury of reinventing the plot, nor would it have been appropriate for him to throw in some language about “I’m a slave here because I don’t want to be a prostitute there.” Instead, he has Cinderella unconvincingly explain that because her parents loved the house, and she loved her parents, staying with the house is the only way she can honor them and remain close to them. That’s pretty thin gruel to explain a lifetime of domestic slavery.

The bottom line, of course, as I tried to explain to my cynic, is that there is simply no way you can make Cinderella a modern woman. To enjoy the movie, you must have a complete suspension of disbelief and accept that it’s reasonable for a lovely, intelligent, educated young woman meekly to accept the abuse heaped upon her.

In recognition of 21st century mores, Branagh also had a multiracial cast. The Prince’s Captain of the Guards, played by a very appealing Nonso Anozie, is a warm, kind, funny man who just happens to be a darker color than the prince. That is, Branagh focused closely on the personalities, not the colors, which is the way it should be.

There’s also some back plot Branagh adds regarding the stepmother, but I’m not going to give it away here. I’ll just say that it usefully fills out holes in the original plot.

The biggest change Branagh makes from the original movie is also his worst decision: He did away with the music. We first heard “A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes” and “Bibbity Bobbity Boo” only when the credits rolled. Otherwise, the score was just some sort of vague romantic pap that added nothing and actually disappointed because it had no charm.

Other than those changes, the movie is a visually exquisite rendering of a charming, innocent, animated classic. It starts, as the original did, with a much-loved little girl living in a beautiful château in a charming kingdom. Then, the fiercely elegant stepmother and her two nasty stepdaughters move in and, when the father dies, these cruel shrews relegate Cinderella to the attic, the kitchen, and the comfort of a few mice.

The Prince has a ball, the fairy godmother saves the day by getting Cinderella to the ball, she and the Prince fall in love, she runs away at midnight, he hunts her down, and they live happily ever after. Kind of boring when you think about it….

So, what makes the movie worth seeing? It’s primarily worth seeing because it’s eye-candy. It really is one of the prettiest movies I’ve ever seen. As I mentioned, Branagh has a mid-19th century sensibility and every scene has that Victorian sweet, flowery, wholesome, gilded-yet-innocent beauty. The Chateau is exquisite and filled with flowers. The forest where Cinderella and the Prince first meet is a verdant paradise. The palace is magnificent and the ball breathtaking.

And the costumes. Oh my lord! The costumes are incredible. Whoever designed Cinderella’s ball gown is a master of fabric engineering. It has a life of its own, moving around her like a soft, fluid, ever-changing bell. And at the end, her wedding gown? Well, I’d say “Yes” to that dress any time. It helps that, whether through CGI or good corseting, Cinderella has a Scarlet O’Hara waist. This may offend the feminists, but there’s definitely something attractive about that 19th century princess silhouette.

The stepmother and stepsisters also had ravishing costumes. The stepmother was frighteningly elegant, while the stepsisters were a delightful riot of tacky colors and shapes. Every costume change elicited a delighted “ah!” from the almost entirely female audience.

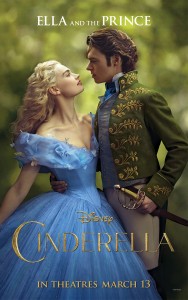

Not only did Branagh pay attention to the movie’s “look,” he did an excellent job casting the movie. Lily James, who plays Cinderella, is not classically beautiful, but she’s got this soft, warm look that makes her perfect for a young woman whose motto (given to her by her mother on the latter’s death-bed) is “Have courage and be kind.” As noted above, given that Cinderella opted to be a household slave, the courage part was a bit hard for modern audiences to grasp, but James really radiated wholesome, heartfelt kindness.

Cate Blanchett was wonderful as the wicked stepmother. She reminded me in looks and build of Katherine Hepburn, only she was Kate’s really mean and evil side. It helps that she has that beautiful, sinuous voice.

Richard Madden played the Prince and was adequate. It’s not a very nice role — he’s not much of a manly man in his silly court costumes — but Madden worked it hard, trying to be a cheerfully twinkling young heir to the throne, and a New Age sensitive prince to Cinderella. It helps that he has very pretty blue eyes.

The really pleasant surprise was Sophie McShera as Drisella. As is the case for Lily James, McShera is familiar to American audiences because of Downton Abbey, in which she plays Daisy, the invariably dour, whiny kitchen maid. I expected her to play a sullen stepsister. She didn’t. Instead, she played an over-the-top harridan with gusto and glee. McShera is a good enough actress that she never took it too far, either. She was funny, without being crude or vulgar. I was impressed.

As the fairy godmother, Helena Bonham Carter did her usual excellent job. I don’t know that she’s ever turned in a bad performance, and her slightly manic fairy godmother was no exception.

The last good word for the movie needs to go to the animators. While it’s not an animated movie per se, I’m pretty sure that 95% of the scenes involved some animation. Sometimes it was so subtle I only realized after the fact that animators had been at work augmenting a scene. At other times, as with Cinderella’s two transformations — one before and one after the ball — it was stunning. The animators kept the animation incredibly fluid, and often quite amusing, without ever sacrificing the visual beauty that underlies ever scene in the film.

If I had to give this movie a numerical ranking, I’d be at a loss. For the cynical, it’s a one. For those who enjoy eye-candy, it’s a definite five. Taking the whole package — the incredible beauty, the good casting, the very slow pace, the unbelievable-in-the-modern-era plot, the reverence, and the adulterated sweetness — well, I don’t know what I’d give it. This is a movie that is going to cater to a very specific audience. I’m that audience. And apparently 10-year-old girls are that audience.

One other thing: One of the ways Disney drew people to the film was to promise an original short based upon Disney’s Frozen. Disney has announced that it will be making a sequel that will presumably get Elsa hooked up with some nice young man. The short was gorgeous to look at (more eye candy), but the plot was almost unpleasantly surreal, and the song was just awful. It was no surprise at the end to learn that Joss Whedon and Christophe Beck, who wrote Frozen’s memorable score, had nothing to do with this short. If you’re going to watch the short, turn the sound off, and just have some nice music (maybe the score from a Tchaikovsky ballet) on in the background.