Feminist claims that bad consensual sex equals rape victimize women just as surely as the McMartin trials victimized children

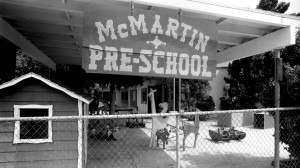

Do you remember the McMartin preschool case in the mid- to late-1980s, when the owners of a small, family-run preschool found themselves accused of satanic sexual debauchery with the children in their care? Although the McMartin case was the most widely publicized, and therefore the most memorable, case, there were similar cases popping up all over the United States.

Do you remember the McMartin preschool case in the mid- to late-1980s, when the owners of a small, family-run preschool found themselves accused of satanic sexual debauchery with the children in their care? Although the McMartin case was the most widely publicized, and therefore the most memorable, case, there were similar cases popping up all over the United States.

Each case would begin with a mother reporting that her child had said something that indicated he or she was the victim of sexual abuse at the preschool. Investigators and child therapists would move in and, next thing you knew, scores of employees and owners were suddenly being accused of the most heinous crimes.

Significantly, these accusations didn’t even stop with ordinary sexual molestation. Instead, they invariably included additional bizarre behaviors such bestiality, animal sacrifice, and even human sacrifice. Looked at objectively, without the accompanying media-fed hysteria, the charges sounded every bit as ridiculous as the claims made almost three hundred years before in Salem, Massachusetts. Needless to say, as in Salem, a lot of lives were irrevocably destroyed before the hysteria finally ended.

One of the things that finally brought the witch hunt to an end was the discovery that young children are simply dreadful witnesses. When the investigators and child therapists got hold of the children, they started off by asking the kids leading, or simply factually detailed, questions. The children would deny that any of the claimed practices occurred. By the next interview, the children had incorporated those questions into their memory banks and admitted that the practices had occurred. Even worse, as the interviews continued, the children began embroidering upon and making ever more lurid these implanted “memories.”

As a Wikipedia article on the Day-care sex-abuse hysteria accurately states:

Children are vulnerable to outside influences that lead to fabrication of testimony.[63] Their testimony can be influenced in a variety of ways. Maggie Bruck in her article published by the American Psychological Association wrote that children incorporate aspects of the interviewer’s questions into their answers in an attempt to tell the interviewer what the child believes is being sought.[64] Studies also show that when adults ask children questions that do not make sense (such as “is milk bigger than water?” or “is red heavier than yellow?”), most children will offer an answer, believing that there is an answer to be given, rather than understand the absurdity of the question.[65]Furthermore, repeated questioning of children causes them to change their answers. This is because the children perceive the repeated questioning as a sign that they did not give the “correct” answer previously.[66] Children are also especially susceptible to leading and suggestive questions.[67]

Some studies have shown that only a small percentage of children produce fictitious reports of sexual abuse on their own.[68][69][70][71] Some studies have shown that children understate occurrences of abuse.[72][73][74]

Interviewer bias also plays a role in shaping child testimony. When an interviewer has a preconceived notion as to the truth of the matter being investigated, the questioning is conducted in a manner to extract statements that support these beliefs.[66] As a result, evidence that could disprove the belief is never sought by the interviewer. Additionally, positive reinforcement by the interviewer can taint child testimony. Often such reinforcement is given to encourage a spirit of cooperation by the child, but the impartial tone can quickly disappear as the interviewer nods, smiles, or offers verbal encouragement to “helpful” statements.[66] Some studies show that when interviewers make reassuring statements to child witnesses, the children are more likely to fabricate stories of past events that never occurred.[64]

Peer pressure also influences children to fabricate stories. Studies show that when a child witness is told that his or her friends have already testified that certain events occurred, the child witness was more likely to create a matching story.[75] The status of the interviewer can also influence a child’s testimony — the more authority an interviewer has such as a police officer, the more likely a child is to comply with that person’s agenda.[76]

I was a young lawyer back in 1987, when the McMartin case was at its peak, and a lot of legal publications suddenly started running articles about the difficulties of getting honest, accurate testimony from very young children. I was very struck by studies showing that children’s memories are extremely malleable and that this malleability, when combined with children’s admirable imaginations, can create terrible, damaging lies.

Back in the day, when it became apparent that all these preschool cases were travesties, and that scores of decent adults had been falsely accused of horrific crimes, sympathy flowed to the adults as the real victims of the witch hunt. I, however, have often wondered about all those children. Instead of their innocent little minds being gardens of bright images, darkened only by the usual childhood fears of things that go bump in the night, these children’s minds had been polluted with horribly obscene images of perverse sex, bestiality, and human sacrifice. It was as if an endless loop of ISIS depredations had been planted in their brains.

Instead of having been “raped” by satanic teachers, these little children were just as surely “raped” by the therapists and investigators who created and encouraged those dreadful images in their heads. Although the children didn’t begin as victims, they ended up that way. Today, feminists are imposing the same type of rape on today’s young women, because the feminists have simultaneously encouraged young women to accept casual sex as the norm while defining rape down to include any sexual activity, including consensual sex, that leaves the woman feeling uncomfortable about the experience.

In a less hysterical (and more traditionally moral time), rape was understood to be a manifestly non-consensual sexual penetration or forced oral sex, one that was based in physical threats or extreme coercion. That standard was pretty damn clear.

The problem for women back in the day was that, if they weren’t pure as driven snow, our culture said either (a) that they’d asked for it or (b) that there’s no such thing as rape when the women isn’t a virgin or when it’s the husband who brutalizes the woman. Thankfully, we have put those days behind us.

Having abandoned that barbaric standard (although it’s one that still flowers in the Muslim world), we’ve gone to the opposite extreme. We define “rape” so broadly that, even when the young women haven’t been raped, they’ve still been victimized because they’ve been told that they are victims.

In an earlier post, I referred to Emma Sulkowicz, aka Mattress Girl, the Columbia University student who made quite a name for herself by carrying around the mattress on which, she said, she was raped, only to have a callous university refuse to help her. I also referenced Lena Dunham, who wrote an autobiography in which she accused an unnamed, but clearly identifiable, campus Republican of having raped her.

In an earlier post, I referred to Emma Sulkowicz, aka Mattress Girl, the Columbia University student who made quite a name for herself by carrying around the mattress on which, she said, she was raped, only to have a callous university refuse to help her. I also referenced Lena Dunham, who wrote an autobiography in which she accused an unnamed, but clearly identifiable, campus Republican of having raped her.

In both cases, the truth was quite different. Sulkowicz’s alleged rapist, Jean-Paul Nungesser has now filed suit against Columbia University and others complaining of the way they allowed Sulkowicz to slander him for years. I predict that, even if the university manages to weasel out of paying him damages, the trial will establish conclusively that Sulkowicz was not raped, at least as the term is understood by normal people who haven’t been indoctrinated by campus feminists.

Nungesser has actual evidence on his side, rather than mere accusations or denials. He was able to recover the texts that Sulkowicz sent him before the alleged “rape,” which show her actively trying to bed him and requesting the anal sex he was later said to have forced upon her, as well as texts from after the alleged “rape,” in which she continued to hound him and profess her affection for him.

Most reporters, presaging the Rolling Stone debacle vis-a-vis the alleged University of Virginia gang rape, never bothered to speak to Nungesser to hear his side of the story. Thrilled by the striking visual of the pretty Sulkowicz staggering around under a mattress, media hacks bought her story hook, line, and sinker. When an actual investigative journalist, Cathy Young, tried to interview Sulkowicz in a way that suggested doubt about the latter’s narrative, Sulkowicz, who had paraded her life in the media for months, turned around and accused Young of re-raping her:

I have already been violated by both Paul and Columbia University once. It is extremely upsetting that Paul would violate me again — this time, with the help of a reporter, Cathy Young. I just wanted to fix the problem of sexual assault on campus — I never wanted this to be an excuse for people to dig through my private Facebook messages and frame them in a way as to cast doubt on my character. It’s unfair and disgusting that Paul and Cathy would treat personal life as a mine that they can dig through and harvest for publicity and Paul’s public image.

Think carefully about that hyperbolic, hysterical, defensive language now that you know about Sulkowicz’s sexually aggressive and affection texts to Nungasser, both before and after her alleged “rape.” Also, think carefully about the positive attention that Sulkowicz garnered with her libelous performance art:

It would be difficult to overstate the adulation showered upon her: She won the National Organization for Women’s Susan B. Anthony Award and the Feminist Majority Foundation’s Ms. Wonder Award; she was the subject of a glowing New York Magazine profile (“she’s the type of hipster-nerd who rules the world these days“); she was invited to this year’s State of the Union as a guest of New York senator Kirsten Gillibrand; earlier this month, United Nations ambassador Samantha Power likened Sulkowicz to women fighting for their rights in Afghanistan; the “art” itself was reviewed in the New York Times. (Assessment: “Analogies to the Stations of the Cross may come to mind.”)

In light of that adulation, it’s useful to learn another fact, this one garnered from studies done in the legal field during the 1980s: In mass tort cases — that is, cases involving the same defendant and similarly situated plaintiffs — those plaintiffs who settled immediately received substantially less money than those who stayed the course, and significantly less money than those who took their claims all the way to trial. Staying the course, though, may not have been a wise choice. The plaintiffs who went for the big bucks paid a price: they didn’t recover as well as the settling plaintiffs, even though their injuries were more or less the same.

What was different was the non-settling plaintiffs’ commitment to being a victim. Their cases required them to re-live the accident over and over for discovery purposes and the realities of trial subtly discouraged them from improving physically. After all, the jury will be less impressed if you come bouncing into the courtroom, fresh off the tennis court, after which you try to convince them that the defendant’s acts left lasting scars, than they’ll be if you are wheeled into the courtroom with crutches clutched across your lap and a large brace encircling your neck.

The plaintiffs who stuck it out weren’t faking their ongoing suffering. They just had no incentive to improve. One could say the same of Sulkowicz. While I don’t believe she was raped (I tend to trust contemporaneous texts more than feminist inspired performance art), even if she was indeed raped, the adulation the media and the political world showered on her encouraged her to remain stuck in the moment. She couldn’t move beyond her trauma, which is the healthy thing to do, but instead stayed in place, endlessly reliving it — and getting rewarded for doing so.

And what about Lena Dunham? Again, the reality was very different from her slanderous announcement that a campus Republican had raped her. Deconstructing her narrative revealed something quite different.

And what about Lena Dunham? Again, the reality was very different from her slanderous announcement that a campus Republican had raped her. Deconstructing her narrative revealed something quite different.

According to Time Magazine, the first version of Dunham’s “rape” story went as follows (Time sets the scene, followed by Dunham’s own words):

The real tale — or what she remembers of it — is much more painful. It begins at a party where Dunham is alone, drunk and high on Xanax and cocaine. It’s in that state that she runs into Barry, who she describes as “creepy,” and who sets off an alarm of “uh-oh” in her head as soon as she sees him.

Barry leads me to the parking lot. I tell him to look away. I pull down my tights to pee, and he jams a few of his fingers inside me, like he’s trying to plug me up. I’m not sure whether I can’t stop it or I don’t want to.

Leaving the parking lot, I see my friend Fred. He spies Barry leading me by the arm toward my apartment (apparently I’ve told him where I live), and he calls out my name. I ignore him. When that doesn’t work, he grabs me. Barry disappears for a minute, so its [sic] just Fred and me.

“Don’t do this,” he says.

“You don’t want to walk me home, so just leave me alone,” I slur, expressing some deep hurt I didn’t even know I had. “Just leave me alone.”

He shakes his head. What can he do?

After the two return to her apartment, Dunham does everything she can to convince herself that what’s happening is a choice. “I don’t know how we got here, but I refuse to believe it’s an accident,” she writes. She goes on to describe the event in graphic detail. Once he has forced himself on her, she talks dirty to him, again, to convince herself that she’s making a choice. But she knows she hasn’t given her consent. When she sees the condom in the tree — she definitely did not consent to not using a condom — she struggles away and throws him out.

Earlier in the same Time article, Lena had described the condom situation:

Dunham writes a darkly humorous essay about a time she realized in the middle of sex that a condom she thought her partner had put on was hanging from a nearby plant.

“I think…? the condom’s…? In the tree?” I muttered feverishly.

“Oh,” he said, like he was as shocked as I was. He reached for it as if he was going to put it back on, but I was already up, stumbling towards my couch, which was the closest thing to a garment I could find. I told him he should probably go, chucking his hoodie and boots out the door with him. The next morning, I sat in a shallow bath for half an hour like someone in one of those coming-of-age movies.”

Huffington Post picked up with the second version Dunham wrote in the same autobiography about the same “rape” scene:

At the beginning of the next chapter, titled “Barry,” she backtracks, writing:

I’m an unreliable narrator … mostly because in another essay in this book I describe a sexual encounter with a mustachioed campus Republican as the upsetting but educational choice of a girl who was new to sex when, in fact, it didn’t feel like a choice at all.

She then retells some events from the condom-in-a-tree night in graphic detail.

“Barry leads me to the parking lot,” she writes. “I tell him to look away. I pull down my tights to pee, and he jams a few of his fingers inside me, like he’s trying to plug me up. I’m not sure whether I can’t stop it or I don’t want to.”

The two then go back to her apartment, and Dunham — in an attempt to convince herself that she’d given consent — talks dirty to him as he forces himself on her.

What stands out clearly is that, each step of the way, Dunham gave active or passive consent even her intoxication wasn’t enough for her to enjoy “Barry’s” advances. If one is to trust her own narration (either version A or version B), Dunham went along with everything right up until she realized the condom was missing, at which point she protested and “Barry the Republican” immediately stopped. Step by step, once sees a narrative of drug and alcohol abuse, diminished responsibility, and consensual conduct:

1. Dunham voluntarily ingested a potent cocktail of alcohol, Xanax, and cocaine.

2. “Barry” “leads” Dunham to a parking lot, which means she went willingly. He didn’t drag her, trick her, coerce her, stalk her, or anything else. Because Dunham had incapacitated herself, she ignored the aversion she might have felt if compos mentis. “Barry” had no reason to believe that Dunham was doing something against her will or that he was forcing himself on a reluctant person.

3. Dunham directed “Barry” to her apartment, which “Barry” could reasonably construe as yet another indicator that Dunham was willing to be in his company.

4. Dunham’s friend Fred, suspecting that she’s in the grip of beer (and cocaine, and Xanax) goggle mania, tried to stop her from going off with “Barry.” Dunham fiercely disavowed Fred’s efforts and, again, threw herself at “Barry.” Dunham had a lot of opportunities to say “no,” but repeatedly, sometimes aggressively, said “yes.”

5. In a parking lot, Dunham took her clothes off in front of “Barry” (unless, that is, she peed through her pants). “Barry,” not unreasonably, saw this as an invitation for him to fondle her genitals. Although this wasn’t a pleasant experience, Dunham again acquiesced.

6. Suddenly, the narrative shifts and the sources I’ve referenced above announce, without detail, that Barry somehow “he forced himself on her.” After the fact, Dunham complains that, all her “yes” signals notwithstanding (being “on the prowl,” following him out of a party, taking her clothes off and peeing in front of him, taking him to her apartment), “at no moment did I consent to being handled that way. I never gave him permission to be rough, to stick himself inside me without a barrier between us. I never gave him permission.”

[I concede here that, not having read the book, I can only rely on quotations from the book that are available online . . . and none of those quotations describes precisely how “Barry” “forced” himself on Dunham, or was rough with her. I can, however, reach some conclusions based upon what Dunham herself says about her conduct during the sexual encounter.]

7. During sex, Dunham admitted that she engaged in conduct that would make any reasonable person believe the sexual activity was consensual. Aside from the pre-sex come-ons (throwing away her inhibitions with intoxicants, leaving a party with him, getting naked with him), she also admitted to encouraging “Barry” with dirty talk. “Barry” could not possibly have understood that she was just trying to encourage herself.

8. Dunham also acknowledged that they were both trying to use a condom, which again implies consent on her part. Just as importantly, Dunham explicitly states that, when she finally realized that the condom never made it onto “Barry”, “Barry,” albeit reluctantly, stopped.

So, leaving aside the hysterical accusations that the media so excitedly relayed, here’s what really happened: Dunham, a depressed, intoxicated person, voluntarily got wasted and went off with the first guy who asked. The sex was lousy (it usually is if at least one of the participants is wasted), but what totally freaked her out was the missing condom. At that point, she panicked, because of possible consequences, such as pregnancy or a loathsome disease.

Things went from misrepresented (and pathetic) to slanderous when Breitbart’s dogged investigative reporting revealed that Dunham’s story could not be true: The sole Republican on campus who fit Dunham’s description of “Barry” could not have engaged in sex with Dunham, making her story utterly libelous. It’s possible that Dunham had the night of sex described, but she was not “raped” by the sole campus Republican.

So, what we end up with is two women, both of whom claimed to be raped, both of whom were lionized by the Leftist establishment because of these claims, and both of whom turned out to have lied about their rapes. Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think either of those girls felt as if she had lied. Instead, each girl bought into the feminist narrative that controls American college campuses. It holds that, if you later feel bad about the sex you had, you must have been raped. Let me state that plainly: Despite consensual activity, each girl was indoctrinated to view herself as a rape victim.

Dunham’s and Sulkowicz’s stories are not unique. All over America, in campuses and post-college Millennial enclaves, young women are waking up the morning following a consensual sexual encounter and, after deciding that the encounter didn’t make them feel good or enhance their sense of respect, concluding that they were raped and are therefore victims. This is so common there’s even a name for it: Gray rape. Of course, in no time other than the present would “gray rape” be called rape. Instead, it would be called “stupid sex.”

Women who have had stupid sex feel mad at themselves. They feel disappointed in themselves. They’re embarrassed by their conduct. All of that — but they are not victims. Instead, they are young people who made a stupid decision and, if they’re smarter than that poor decision-making indicates, they vow not to make that kind of stupid decision again, at which point they move on with their lives.

Women who have been raped, however, are victims. They feel self-loathing. They feel disgust. They begin to fear men, whom they view as predators. They feel helpless. Moreover, because women are never to be blamed for the decisions and conduct that lead to rape, and since these women have convinced themselves that their sordid, but consensual sex, was rape, the result is that they cannot analyze their behavior and pursue a course of action that allows them to engage safely and smartly with men in the future.

These women are in the same situation as those little preschoolers who were long ago convinced that they had been raped, that they’d seen animals raped, that they’d seen animals sacrificed to Satan, and all of the other sorts of appalling stuff that never happened. While the preschools didn’t victimize those children, the system did.

Here, the Dunhams and Sulkowiczs of America haven’t been raped by the men they accuse. Instead, they’ve been raped by a feminist ideology that permeates their lives and that convinces them that, even as they voluntarily sleep within any man who doesn’t actively disgust them, each of those encounters is a form of rape.

This is the reductio ad absurdum of the intersection between feminism, sex, and rape. Andrea Dworkin’s once marginal claim that it’s entirely possible to view all heterosexual sex, by definition, as a form of rape, has become the cultural norm on college campuses. This is an appalling disservice to an entire generation of men and women, turning the former into predators when they’re not, and turning the latter into victims when they’re not that either.

I know a young man who has responded to the paranoia rampant among his generation by confining his sexual activities to prostitutes. As far as he’s concerned, as long as he uses a condom, it’s the safest sex around. And sadly, the more I hear about what’s happening on America’s college campuses, the more I can see his point of view. (This is not an endorsement of prostitution. Margo St. James notwithstanding, I do not see prostitutes as strong women using and profiting from men. I’m old-fashioned enough to see as an inherently abusive, degrading, and dehumanizing activity that may be as old as humankind, but that is still a stain on the collective human soul.)