Heroin: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best.”

A book about the heroin crisis in America shows Trump was right when he said that, with illegal aliens, Mexico was not “sending their best” people.

You might recognize the quotation that stands as the title to this post: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best.” It comes from a June 2016 speech Trump made about illegal aliens in the United States.

You might recognize the quotation that stands as the title to this post: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best.” It comes from a June 2016 speech Trump made about illegal aliens in the United States.

Shortly after saying that Mexico is not sending its “best” people to the U.S., Trump added that, while Mexico was hanging onto its best, it was sending the U.S. a raft of less savory characters, including drug dealers and rapists. Here’s the entire section of the speech in which Trump said that Mexico’s good citizens stay in Mexico, while the miscreants come to America as a new happy hunting ground:

The U.S. has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems.

Thank you. It’s true, and these are the best and the finest. When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.

But I speak to border guards and they tell us what we’re getting. And it only makes common sense. It only makes common sense. They’re sending us not the right people.

While the maddened Progs latched onto the above speech to mean that Trump was a racist bigot who called all Mexicans rapists and drug dealers, I always understood Trump’s statement to mean one thing and one thing only: When a country — say, “County A” — is in charge of its own border, it gets to make choices about immigrants. And when it’s allowed to choose, it chooses immigrants who are upstanding citizens who can and will make solid contributions to their new country.

However, when another country — we’ll call it “Country B” — gets to call the shots about Country A’s immigration policy, the likelihood is that Country B will actively hang onto its productive citizens or actively encourage its less productive ones to head into Country A. Sometimes it will do both.

As I understand things, Trump’s statement was never about race nor was it even about things unique to Mexican culture. What he said, and said correctly in his oblique shorthand, is that America fares very poorly when it hands its immigration policy over to Mexico.

Ann Coulter has already discussed how that Mexican-controlled American immigration policy works when it comes to rapists. The short answer is “not well.” The longer answer is “Mexican illegal aliens commit a disproportionate number of pedophile rapes in America.”

The same can be said for the Mexican-controlled American immigration policy when it comes to illegal drugs. Things do not work out well for Americans.

Pardon my meandering style, but I think it’s helpful to give a little back story here, if only to prove the bona fides of the book I’m going to discuss in this post. My interest in this subject started a couple of weeks ago, after I watched an HBO documentary about opioid use in America. I wrote a post generally praising the documentary for showing what a scourge heroin and other opiate addiction is for those who have to live with or care for the addict, but adding that I found some of its unsupported statements suspect.

In response to the questions I raised in my post, Neo-Neocon sent me a link to a Sally Satel article that perfectly answered my questions. Satel is an extremely reputable conservative physician and writer. In a second post, I linked to the Satel article to explain that HBO was correct about the immensity of the scourge, but (as is to be expected from HBO) misrepresented other data.

Sally Satel had her own resource for some of her data and that was Sam Quinones’s Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic. While on a road trip, I listened to six or so hours of Quinones’s book. He’s not a great writer, and the book could have used more rigorous editing, but as Satel recognized, he gets his point across.

The book’s structure has alternating chapters that describe two building crises that eventually merge into the current opioid epidemic. The first concerns prescription opioid abuse, led by Ocycontin.

OxyContin abuse arose due to a perfect storm of factors in the late 1980s and early 1990s:

(1) the medical community’s misinterpretation of a short letter to a medical journal reporting that supervised, but significant, opioid use on individuals with severe pain while in the hospital did not lead to addiction — a paragraph that morphed into the blanket claim that all chronic pain could be treated with opioids without addiction risks;

(2) Purdue Pharamceuticals’ development of OxyContin, which allowed the incredibly strong opioid OxyCodone to be administered in a time-released pill;

(3) the new theory that pain was the “fifth” vital sign that had to be treated aggressively;

(4) Purdue’s decision to run with the preceding three factors to create the most aggressive marketing campaign in pharmaceutical history;

(5) The fact that credulous doctors allowed the preceding four factors to cloud their judgment and to accept that opioids delivered slowly would not be addictive;

(6) The insurance company’s delight that a pill could treat pain, an approach significantly cheaper than multi-pronged efforts involving psychological and physical approaches to pain management; and

(7) and the growth of fake pain clinics in which criminally-inclined, greedy doctors issued hundreds of opioid prescriptions a day in exchange for $250 “doctor’s visits” that required cash payments and lasted all of 90 seconds.

Before I go further, please let me explain how amazingly stupid doctors were to buy into factors one through four. Any sentient person — or at least any marginally-informed doctor — knows that there are two factors to opium addiction. The first one is the mental craving for the incredible high, along with the corresponding emotional low when the high wears off. The second factor is the addicted body’s physical need for the opioid. This second factor is entirely separate from the high and low. When a body that’s been habituated to opioids is then deprived of the drug, it reacts angrily:

Opiate withdrawal symptoms can include:

- Strong cravings

- Nausea

- Cramps

- Sweating

- Chills

- Goose bumps

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Shakes

- Irritation

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Muscle aches

- Runny nose

- Yawning

- Insomnia

- Dilated pupils

Couple those physical miseries with the emotional low and the mental craving for the high, and you’re going to end up with someone seriously committed to the drug. Indeed, Quinones’ book makes clear that every addicts’ first goal is to stave off withdrawal symptoms. Candy does a decent job of conveying the physical agony a junkie goes through (language warning).

Notwithstanding the physical side of withdrawal, Purdue marketed OxyContin by saying that, because the opioid was given through a timed-release format, it didn’t create the usual emotional highs and lows associated with opioids, therefore minimizing the risk that the user would become addicted. What’s staggering is that no one seemed to recognize that limiting the emotional addiction wouldn’t do anything to affect the physical addiction.

I don’t say this just because I read it somewhere. I say this because, thirty years ago, I used to go to an old-fashioned family physician who treated my migraines with Darvocet, a narcotic pain reliever that was banned in 2010 because of its dangerous effect on people’s hearts.

When I started using Darvocet, I’d get migraines about twice a month. Eventually, I was getting “migraines” every day and the only relief was Darvocet. There were no highs or lows; instead, there was just pain and then, once I’d popped a Darvocet, the absence of pain. I was also sleepy most of the time, which negatively affected my early legal career.

It was only four years into this “treatment” that another doctor told me that I was not having migraines that were cured by Darvocet. Instead, I was having withdrawal that had me craving the hair of the dog that bit me. The moment I understood that cycle, I stopped taking the Darvocet (in a safe manner, by titrating down so that I wouldn’t have serious withdrawal symptoms). When I stopped using Darvocet, I stopped having daily “migraines” too. (And yes, I still get periodic migraines, but I treat them without any opioids or narcotics.)

Thirty years ago, I was a naive young woman in the hands of a well-intentioned, but old-fashioned, practitioner. Nowadays, though, and certainly by the 1990s, there was absolutely no reason for doctors to think that erasing the mental highs and lows of opioid addiction would negate the body’s physical craving for the drug. And yet that’s exactly what doctors did think. Shame on them.

So, that’s the prescription drug side of the equation when it comes to America’s opioid addiction as Quinones describes it. Despite my long digression, what I really want to focus on is the heroin side.

As Quinones explains it, up until the 1990s, heroin in America was a wholesale business. The drug came in from faraway places in Asia and Latin America, and went through numerous wholesalers before it hit the streets.

At each level, in addition to take a financial cut (as all middlemen do), the wholesalers actually cut the drug as well. Its purity declined so greatly that, by the time it hit the streets, addicts would have to spend as much as $100 a day just to quell the physical withdrawal symptoms. If they wanted a high above and beyond quelling their withdrawal, they’d have to spend another $100.

Things changed when someone realized that a little state in Mexico — Nayarit — grew fabulous opium poppies, in great abundance. These poppies, in turn, produced vast quantities of pure black tar heroin.

I missed the first few chapters of Dreamland, as I was traveling with people who had already listened to the book for a while. It wasn’t hard to grasp, though, that someone in Nayarit figured out that America was a prime market for this black tar heroin.

What distinguished the black tar heroin sales from traditional heroin sales was that the Nayarit men used a new business model: The men, who mostly came from, Xalisco, a very poor village in Nayarit near the poppy fields, sold their uncut product directly to the users. Moreover, they sold it cheap, making their money from volume sales. They targeted areas that weren’t already owned by the Mafia, whom they feared, or black dealers, whom they feared and hated in an uncomplicated, racist way.

Looking for safe, new territory, the Mexican dealers spread out in white communities, where their personal risk would be low. The drug importers would bring in young men from Nayarit who, in response to a message on their pager, would drive to meet the user and deliver a small baggy of the drug for just a few dollars. The Nayarit boys did not use the stuff themselves and, being incredibly poor boys from Mexico, were happy to take a flat salary that converted to real wealth in their home village.

The whole system was pure, brilliant capitalism. The only problem is that the product it was peddling was poison.

When white Ocycontin abusers met up with Mexican black tar dealers in towns across Middle America — boom!!! Big opioid epidemic. (By the way, it seems to me, without having read the entire book so I’m guessing here, that the current scourge isn’t necessarily that there are more heroin users in America than in the post. Instead, the issue is the rise white users in Middle America who are routinely overdosing on pure heroin that was previously unavailable anywhere in America.)

What Quinones studiously avoids addressing is how all those Mexicans came to America to sell drugs. In the part of the book I heard, he let the truth slip only once, when he talked about how the leaders of these teams of Xalisco salesmen kept away from law enforcement. Their technique was to package the pure drug in tiny balloons that the Xalisco salesman would hold in his mouth. If law enforcement stopped the salesman, he simply swallowed the bags. If the police searched him or his car, they’d find nothing.

Quinones explains the reason behind this approach: If the boys were arrested, as illegals they’d simply be deported. However, if they were illegals dealing drugs, they’d end up in jail.

Yup, they were illegals. Moreover, as the book makes clear, they were passing back and forth across America’s southern border as if it did not even exist.

These illegal aliens were the drug dealers Trump was talking about when he said that Mexico is not sending her best. Trump was exaggerating, of course, but his supporters understood the difference. Amongst the millions of illegal aliens in America, there are good people who are making a logical choice to escape the poverty into Mexico for the possibility of prosperity in America. They work hard and the only thing I hold, and others, against them is that their mere presence in America is an offense to the rule of law.

But these drug dealers, on the other hand. . . . Decades of lax border policies (which escalated on Obama’s watch) meant that America had no chance to screen people before they came in. After all, what’s the likelihood, if America followed her own laws, that she would have simply let in hundreds, even thousands, of broke, unaccompanied young Mexican boys who had no skills and no American sponsor? Our failed border policies invited these men in to exploit American drug users.

Trump was right again.

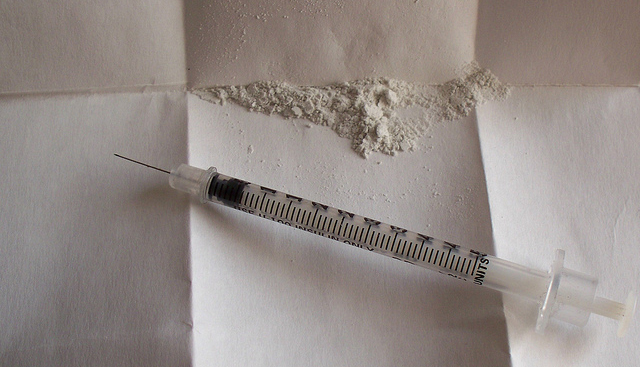

Photo credit: Drugs by Dimitris Kalogeropoylos. Creative Commons license; some rights reserved.