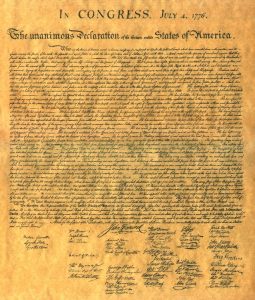

July 4, 1776: The Declaration of Independence Annotated (Updated)

The Declaration of Independence was written for the colonists, to justify our call to arms, and to Britain’s enemies, to assure them of our intent.

Below is the Declaration of Independence annotated and its historical context. Following that are some additional comments on the Declaration and its importance.

Below is the Declaration of Independence annotated and its historical context. Following that are some additional comments on the Declaration and its importance.

Update: Read the Declaration of Independence while you still can. Apparently Facebook recently censored a portion of its publication as “hate speech.”

Historical Commentary: In 1760, Britain was on the verge of finally defeating France in the Seven Years War, the economy was growing, and virtually every American colonist was proud to be a British citizen. Even as Britain, out of misplaced jealousy and greed, slowly tried to strangle its colonies over the next sixteen years, the majority of colonists still wanted nothing more than to remain in the British fold.

That finally changed among a bare majority of patriots after shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, in 1775, and after Thomas Paine published the most read pamphlet in American history, Common Sense, justifying rebellion against Britain. A decision had to be made, though it was not clear that we would declare independence until, after several votes and much debate, we voted to do so on July 2, 1776. The colonists themselves needed a sufficient reason to fight — to create a new nation that would be better than the old. And we needed foreign support, particularly from Britain’s long term enemies, France and the Netherlands. Both would only offer their support to us if we unequivocally proclaimed that our intent was to form a new nation. The Declaration of Independence was commissioned for those two audiences.

Everyone knows Jefferson’s preamble, a restatement of Locke’s natural rights theory that itself is founded on Christianity. It was the high water mark of the English Enlightenment. Jefferson’s preamble provided the philosophical basis for our rebellion and the creation of our new nation.

After Jefferson’s preamble came the specific complaints drafted by joint effort of all of the members of the Second Continental Congress. Everyone knows that the colonists demanded that they only be taxed — and subject to laws — passed by their own governments, not by the Parliament sitting in London. But the members of the Second Continental Congress went far beyond that, setting forth in the Declaration of Independence the “long train of abuses,” to quote Locke, that accumulated over sixteen years and that now justified our rebellion.

As you read this, remember that, in July 1776, the outcome of this rebellion was anything but certain. Moreover, signing the Declaration was a death warrant for the signatories. If they lost the war and were caught, they faced being hanged, drawn and quartered for treason and their families thrown into absolute poverty.

The one high ranking member of the Revolution, Henry Laurens, who was caught by the Brits in 1780, was charged with treason and held in the Tower of London. Fortunately for Laurens, the Brits soon after lost the Battle of Yorktown and Britain exchanged Laurens for Lord Cornwallis, the British commander captured by the Americans at Yorktown.

———-

IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

[This is a generic complaint against the King for retaining power to veto duly passed local laws and likely a specific complaint about the King’s repeated veto of laws passed by Pennsylvania to restrict the slave trade in that colony. ]

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

[In 1764, New York wanted to pass a law to include the Indian tribes, particularly the Six Nations, among the colonies. British Governor Colden agreed privately, but the King sent back instructions to all his governors to stop pursuing this notion until further notice. The colonists waited, but the King “utterly neglected to attend to them.”]

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

[This no doubt refers to the Quebec Act of 1774, that ignored the complaints of British citizens living in Canada and did away with representative government there, establishing in its place a legislative council appointed by the King. It might seem odd that the Second Continental Congress should be concerned with what was happening in Canada, but at this point, some of the members of Congress still held out hope that Canada might join with the lower thirteen colonies in rebellion against the Crown.]

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

[The Boston Port Act of 1774, part of the Intolerable Acts designed to punish Boston and the colony of Massachusetts after the Tea Party, provided in part that the legislature of Massachusetts Bay Colony would, in the future, meet in Salem, not Boston. Similar events happened in Virginia and South Carolina as their respective Royal Governors tried to disrupt intransigent legislatures.]

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

[In 1768 and 1769, Britain’s colonial Secretary ordered all legislatures be dissolved if they adopted the Mass. Circular Letter seeking to unify the colonies and petition the government to rescind the Townshend Acts as unconstitutional. This passage also likely refers to the Massachusetts Government Act of 1774, part of the Intolerable Acts, that functionally ended representative government in Massachusetts. The royal legislatures of the colonies were dissolved individually by the Royal Governors, most in 1775, as they lost control of each colony to the patriots.]

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

[Britain’s practice of dissolving colonial legislative bodies was meant to stop troublesome legislatures and prevent them from conducting the jobs they were elected to do. Though complaining of this practice, this indictment also states the principle that the source of all local law is the people, not the King, and that such dissolutions has among its effects an abrogation of the sovereign’s fundamental duties to defend the colony and maintain the peace. ]

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

[The British Nationality Laws as applied in the American Colonies were a minor but persistent source of irritation between the colonies and Parliament.]

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

[This likely refers to the difficulty the colonies experienced in getting the Board of Trade to approve election districts, judicial bodies and administrative bodies for numerous new communities forming in their “back country” after 1760. In SC and NC, this occurred because people in the Board of Trade had a financial interest in the Court fees that accrued in existing courts, which fees would have been diluted had the Board approved creation of new courts. It led to the largely disastrous vigilante Regulator Movement in NC and SC. ]

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

[Assuring an independent judiciary was an important theme in British history from the 15th to 18th centuries. It was solved in 1701 by The Act Of Settlement which provided that judges had tenure, subject only to recall by Parliament for cause. But Parliament passed a law in 1761 providing that judges in the colonies, most often appointed from among the local populace, served solely at the King’s pleasure and could be removed from office at any time for any reason. ]

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

[This was a very significant cause of the revolution. Beginning with provisions of the Sugar Act of 1764, Britain severely burdened American commerce in an effort to raise revenue and stop smuggling. Parliament significantly increased the number of customs agents in the colonies and gave these agents, as well as judges in the Admiralty Courts and each colony’s Royal Governor, a personal financial stake in the administrative fees and fines arising out of prosecutions for smuggling. The end result was a very abusive and corrupt system that made a mockery of the law and British rights.]

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

[In the 18th century, people were very distrustful of standing Armies as history, from the time of Julius Caesar to Oliver Cromwell, showed that standing armies were always a threat to civilian governments. Indeed, prohibitions against standing armies and forced quartering of armies both appear in the Bill of Rights of 1689. Yet in 1763, after the French and Indian War, Britain opted to maintain an army of 10,000 men in the American colonies, ostensibly to protect against Indians. Colonists objected to the standing army, which they did not see as necessary, and strongly objected to being forced by Parliament to bear part of the cost and maintenance of the army.]

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

[This begins a series of charges against Parliament, for passing legislation effecting and taxing colonists directly, and against the King for his role in approving their laws. The three constitutional documents of English history, the Magna Carta of 1215, the Petition of Rights of 1628, and the English Bill of Rights of 1689 all, in one form or another, provided for people to vote for their representatives and the necessity that their representatives have the power to vote on all laws and taxes binding the people. The colonists were not represented in Parliament and most colonies, by their charters, had been given the sole right to raise taxes and pass laws locally applicable. When Parliament began impinging on those rights and legislating laws on behalf of the colonists without their consent, this became the rallying cry of the colonists.]

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

[Quartering Act of 1765 and the Quartering Act of 1774, the latter of which was part of the Intolerable Acts and which authorized, in certain cases, forced quartering of British soldiers on private property.]

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

[This refers to Administration of Justice Act, also part of the Intolerable Acts, allowed Royal Governors to direct that trials brought against British soldiers and officers for crimes they committed in the colonies be moved to Britain. This would have placed such a burden on local witnesses to spend months travelling to and from Britain, as well as attending trial, all with no compensation other than travel expenses, that it effectively placed British soldiers and officers outside of the law. In addition, in 1773, a customs official was convicted of a local jury in Boston for the murder of 11 year old Christopher Seider when the official fired his gun directly into the middle of a crowd to disperse them. King George III immediately granted the murderer a full pardon.]

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

[The Restraining Acts of 1775 and the Prohibitory Acts were two punitive provisions passed by Britain to break the economic back of those colonies that adopted an embargo against British trade over the Intolerable Acts. The Prohibitory Act went further, declaring the colonies to be in a state of rebellion. It amounted to a declaration of war and authorized a total blockade of the colonies. ]

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

[Stamp Act of 1765; Townshend Acts of 1767, Tea Act of 1773]

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

[In 1764, with the Sugar Act, Britain began using Admiralty Courts to hear criminal and civil cases involving smuggling. These courts were a mockery of British Rights. Cases were heard and decided by a single judge with no jury. A defendant was presumed guilty and had to prove his innocence. Standards for admitting evidence were much lower than in normal courts. There was no right to confront witnesses. And to make it completely corrupt, Admiralty Court judges received commissions based on the value of ships and trade goods they ordered forfeit. ]

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

[This likely refers to two policies. A provision of the Sugar Act allowed a British official to direct that a trial for smuggling be held not in the local Admiralty Court, where the judge would have been a colonist, but in the Vice Admiralty Court that sat in Nova Scotia with a judge appointed directly by the King. The second policy was one proclaimed by Britain but never put into effect. In 1768, the British Secretary for the colonies charged that the attempt, through the Massachusetts Circular Letter, to unify the colonies in peaceful opposition to the Townshend Acts amounted to high treason. Referring to a long outdated law passed under the reign of Henry VIII, Britain claimed the right to bring any colonist to Britain to be tried for a crime amounting to high treason. The colonists strenuously objected to this law in light of their own colonial Charters. The only serious attempt to arrest people for high treason and send them to Britain for trial was General Gage’s march on Concord, one goal of which was to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock.]

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

[This refers to the Quebec Act, of which the colonists were deeply distrustful and angry. One, it expanded the boundaries of Canada into territory claimed by several of the American colonies. Two, it ended representative government in Canada. Three, it did away with British civil law in Canada in favor of French civil law Four, it favored French Roman Catholics. The American colonists religiously pluralistic but for Catholicism which had been the bete noir of British protestants since the days of Europe’s brutal religious wars. The purpose of the Quebec Act was to satisfy the largely French population of that country and insure that Canada did not join the lower thirteen colonies in opposition to the Crown.]

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

[Britain attempted to do this on more than one occasion in colonial history, but by 1776, this indictment probably only referred to the Massachusetts Government Act, also a part of the Intolerable Acts. By this law, the King unilaterally abrogated the charter governing the colony, in all but name did away with representative democracy, going so far as to outlaw town meetings not pre-approved. This was a clear warning to all of the other colonies that they needed to submit to British demands or Britain would impose martial law upon them. The colonists chose a third option.]

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

[This repeats the indictment about the Massachusetts Government Act, but adds a specific complaint against the Declaratory Act, which provided that Parliament had unlimited power to legislate for the colonies in all matters. The Declaratory Act was passed in 1766, at the same time Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act, as a means for Parliament to save face.]

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

[This refers to the Prohibitory Act and the clash of arms at Lexington and Concord, then Bunker Hill.]

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

[In late 1775, the Royal Navy engaged in several raids against civilian targets in coastal towns, culminating most notoriously in the burning of the town of Falmouth. These were shocking acts of terrorism and, in particular, convinced at least one still uncommitted colony, South Carolina, that the colony should join in active rebellion against Britain.]

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

[Britain made extensive use of German mercenaries to augment their forces in the colonies. This was seen as particularly treacherous by the colonists.]

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

[The Prohibitory Act authorized not merely the capture of American ships, but the impressment of any of her crewmen into service aboard British naval ships.]

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

[The Southern colonies had large slave populations. The Royal Governor of Virginia, in late 1775, issued what became known as Dunmore’s Proclamation, offering freedom to any slave owned by a patriot who would take up arms against the patriots. As to the Indians, those who engaged in warfare against the colonists over the past century had a well earned reputation for savagery and attacking civilians of all ages and sexes. For instance, The Long Canes Massacre and the ordeal of Hannah Duston are but two examples. The colonists viewed British efforts to enlist the various Indian tribes to war against the colonists as acts of particular evil. And while the Congress did not know it, when they drafted this passage, the Cherokee Indians, acting at the behest of Britain, had already started their war against the colonists in SC, NC, Georgia and Virginia, in a series of attacks that were supposed to be timed to coincide with the first British offensive of the Revolutionary War outside of Boston, the British attack on Charleston, S.C..]

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

[1774 Petition to the King; 1775 Olive Branch Petition]

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

———-

Many of the concerns of the raised by the colonists in 1776 are unique to their time and place simply because they eventually wrote corrections for them into our Constitution eleven years later. For but one example, the practice of the Crown to dissolve troublesome colonial parliaments upon their whim is not allowed our President by our Constitution. For another, we’ve made mandatory the due process of law in several different provisions of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

But there are concerns in the Declaration of Independence that are every bit as problematic in the modern day. Indeed, there are two very big ones that were at the center of our rebellion in 1776. And those problems aren’t because they are somehow new, but rather they arise out of progressives seeking a way around Art. I, Sec. I, that all legislative authority resides in Congress, and Article V, that limits our nation to two means by which the Constitution may be amended, neither of which is by judicial fiat.

The first is the right of the people to have all of their laws passed by their elected representatives. That worked until a century ago, when progressives introduced regulatory agencies and a Supreme Court was cowed into approving them by FDR’s threat of packing the Supreme Court. Progressives use the regulatory bureaucracy to work fundamental changes to our nation through regulations, all with the force of law, that are never voted upon by our elected representatives — or in truly obscene cases, that have been rejected by Congress. For example, since 2009, we have been passing laws on the proposition that carbon dioxide is a pollutant. In 2009, our elected representatives voted down a bill that would have included regulating carbon as a pollutant. Within months, Obama’s EPA unilaterally declared carbon a pollutant, claiming the power to do so under the Clean Air Act.

A second major concern of the colonists was the judiciary and fair application of the law. Admittedly, the colonists were concerned about a judiciary that was under the influence of the King, whereas our problem today is a judiciary without checks and balances that no longer has fidelity to the rule of law but rather to progressive ideology. And now with the progressives facing loss of a Supreme Court that holds to progressive ideology, they are . . . going back to FDR’s Court Packing scheme.

At any rate, Powerline has posted the comments of two Presidents on the Declaration of Independence. The quotes are so good that I include them below just to memorialize them here for future reference. Please do visit Powerline to read both posts in full. The first comes from a speech given by President Calvin Coolidge on July 4, 1926:

About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful. It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning can not be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction can not lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.

The second exceptional commentary about the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence comes from a speech by Abraham Lincoln in response to a statement by his political rival, Stephen Douglas,“that in my opinion this government of ours is founded on the white basis. It was made by the white man, for the benefit of the white man, to be administered by white men, in such manner as they should determine.” This was Lincoln’s response, given during a speech on July 10, 1858:

Now, it happens that we meet together once every year, sometime about the 4th of July, for some reason or other. These 4th of July gatherings I suppose have their uses. If you will indulge me, I will state what I suppose to be some of them.

We are now a mighty nation, we are thirty—or about thirty millions of people, and we own and inhabit about one-fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years and we discover that we were then a very small people in point of numbers, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a vastly less extent of country,—with vastly less of everything we deem desirable among men,—we look upon the change as exceedingly advantageous to us and to our posterity, and we fix upon something that happened away back, as in some way or other being connected with this rise of prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men, they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity that we now enjoy has come to us.

We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves—we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better men in the age, and race, and country in which we live for these celebrations.

But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have besides these men—descended by blood from our ancestors—among us perhaps half our people who are not descendants at all of these men, they are men who have come from Europe—German, Irish, French and Scandinavian—men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration [loud and long continued applause], and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world. [Applause.]

Now, sirs, for the purpose of squaring things with this idea of “don’t care if slavery is voted up or voted down” [Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” position on the extension of slavery to the territories], for sustaining the Dred Scott decision [A voice—“Hit him again”], for holding that the Declaration of Independence did not mean anything at all, we have Judge Douglas giving his exposition of what the Declaration of Independence means, and we have him saying that the people of America are equal to the people of England. According to his construction, you Germans are not connected with it. Now I ask you in all soberness, if all these things, if indulged in, if ratified, if confirmed and endorsed, if taught to our children, and repeated to them, do not tend to rub out the sentiment of liberty in the country, and to transform this Government into a government of some other form.

Those arguments that are made, that the inferior race are to be treated with as much allowance as they are capable of enjoying; that as much is to be done for them as their condition will allow. What are these arguments? They are the arguments that kings have made for enslaving the people in all ages of the world. You will find that all the arguments in favor of king-craft were of this class; they always bestrode the necks of the people, not that they wanted to do it, but because the people were better off for being ridden.

That is their argument, and this argument of the Judge is the same old serpent that says you work and I eat, you toil and I will enjoy the fruits of it. Turn in whatever way you will—whether it come from the mouth of a King, an excuse for enslaving the people of his country, or from the mouth of men of one race as a reason for enslaving the men of another race, it is all the same old serpent, and I hold if that course of argumentation that is made for the purpose of convincing the public mind that we should not care about this, should be granted, it does not stop with the negro. I should like to know if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle and making exceptions to it where will it stop. If one man says it does not mean a negro, why not another say it does not mean some other man? If that declaration is not the truth, let us get the Statute book, in which we find it and tear it out! Who is so bold as to do it! [Voices—“me” “no one,” &c.] If it is not true let us tear it out! [cries of “no, no,”] let us stick to it then [cheers], let us stand firmly by it then. [Applause.]