A couple of quick points about eugenics, climate change, and art restoration

The eugenics debate from a century ago bears striking similarities to the climate change debate today, while Leftists try to bring racism to old statuary.

I’ve actually been doing paid legal work all day long, with a short deadline, which makes blogging difficult if not impossible. Nevertheless, I wanted to raise two quick points that impinged on my consciousness in the past few days.

I’ve actually been doing paid legal work all day long, with a short deadline, which makes blogging difficult if not impossible. Nevertheless, I wanted to raise two quick points that impinged on my consciousness in the past few days.

Eugenics and climate change. The first point comes about because over the past couple of nights I watched a fairly good PBS documentary about eugenics. While it didn’t mention Margaret Sanger’s racism, it did touch upon a lot of other interesting points about the eugenic craze in America:

- The way in which someone took a scientific theory (evolution) and ran with it;

- “Scientific” research that started with conclusions and forced the data;

- Big money;

- The buy-in of the American elite in the name of expertise, science, and self-improvement;

- The panic about a nation that could be destroyed by “defective” human beings, whether because of birth defects, substance abuse, or inferior race;

- The doubling down as doubt crept in amongst serious researchers; and

- The movement’s eventual failure when it reached its inevitable and extreme conclusion with the Nazis.

If those factors remind you of something, then I’ve successfully made my point, which is that the whole eugenics foofaraw is like a template for climate change hysteria. Just think about the fact that the climate change craze:

- Took a scientific theory and ran with it;

- Larded the theory with dubious “science” towards a predetermined conclusion;

- Got big money;

- Got the buy-in of a hysterical elite in thrall to expertise, science, and self-improvement;

- Turned into an eschatalogical, Manichean panic to prevent the end of the world;

- Saw its true believers double down in the face of opposing evidence; and

- (Finally) seems to be falling under its own weight as it becomes clear to ordinary people that it has no substance and is being used for bad ends (in the case of climate change, to enrich hucksters and impoverish ordinary people around the globe).

The artists’ vision or racism? I’m going to quote something I wrote about my recent trip to Japan:

In 1987, when Czechoslovakia was still part of the communist bloc, I went to Prague. In the historic district, the Prague government had really shined things up, so that old buildings had fresh coats of paint and everything was in good shape. Indeed, it was in better shape than any building several hundred years old ought to be, or so I thought. My idea of purity was to make sure historic sites had that patina of age.

I was wrong.

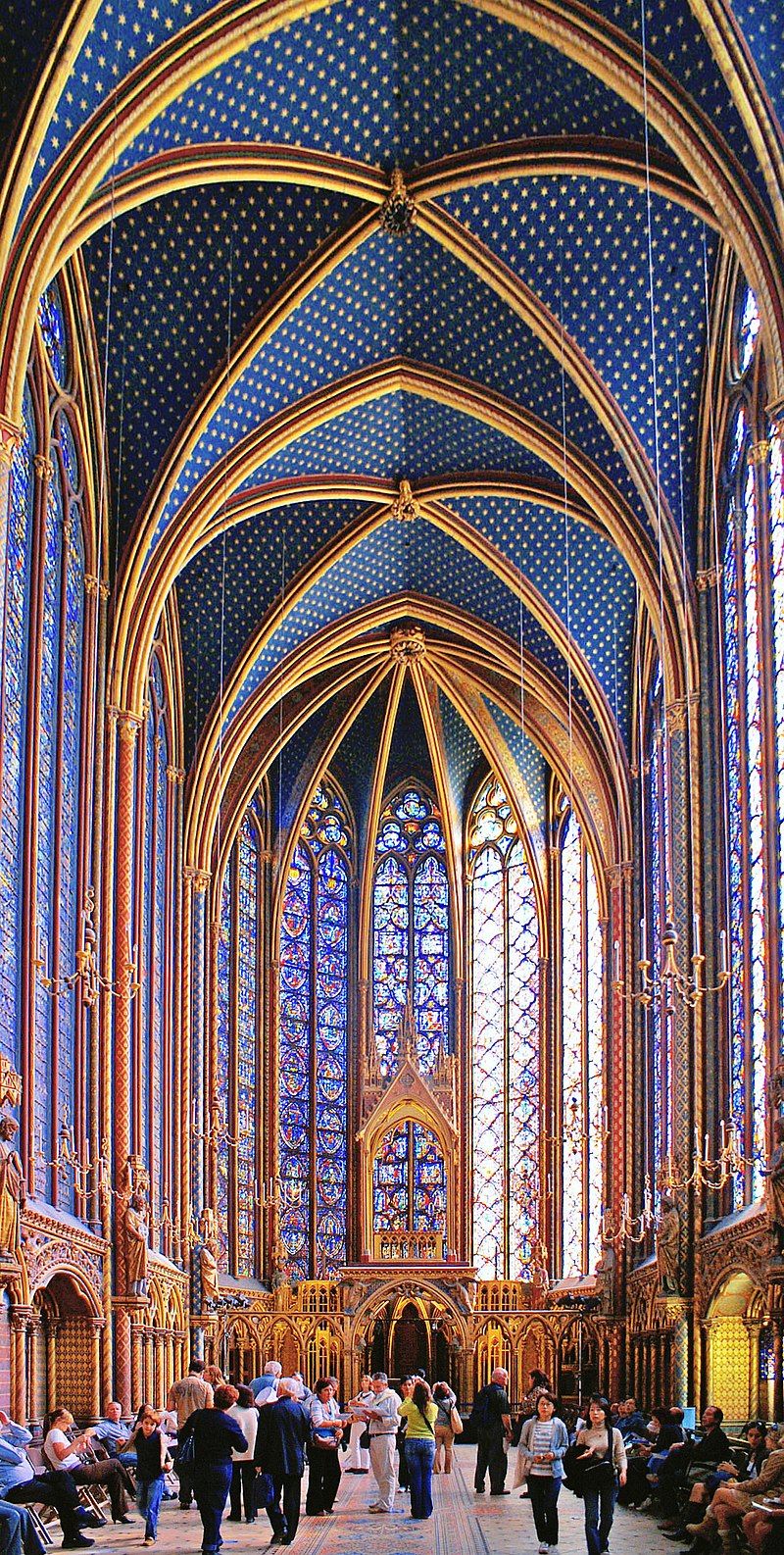

I first got an inkling about how wrong I was when I saw the fully restored Sainte-Chapelle Cathedral in Paris. This gem was constructed in the mid-13th century and has some of the most beautiful stained glass windows in the world. Beginning in the 1980s, France embarked on a vast renovation, which went far beyond restoring the faded stained glass. Instead of just touching up whatever remained in the Cathedral of its original art work, the French decided to restore the Cathedral’s interior so that it looked as its original builders wanted it to look, complete with painted walls and ceilings:

As far as I’m concerned, this is one of the most beautiful interior spaces in the world. And I don’t care that I’m not looking at tastefully gray walls with tiny traces of the original coloring. I appreciate that I am seeing the original builder’s vision.

It’s the same thing with old paintings. For so long, we’ve assumed, quite wrongly, that the original painters used subdued coloring in a quiet, classy way. In fact, that subdued coloring comes about because of yellowed varnish and centuries of dirt and smoke. In reality, painters for hundreds of years saw the world in the same bright colors that we do and they incorporated those brilliant colors into their paintings. If you follow Philip Mould’s twitter feed, you can see examples of this. One of my favorite examples is no longer on his feed, but this Telegraph story reports on it, complete with a short autoplay video.

I mention all this because one of the really amazing sites in Kyoto is Sanjūsangen-dō, a Buddhist temple in Kyoto dating to the 13th century. It’s not only the longest wooden building in the world, but it also houses one thousand Kannon statues, which pretty much all look like each other, as well as 28 individually carved deity statues.

The latter statues are fabulous, because each is an individual, with unique facial features and clothes. Although they’re now just darkened wood, if you look closely, you can still see bright red paint in their open mouths, as well as faint traces of color on their carved clothing. In addition, a sign says that the wooden interior was once brightly painted from stem to stern, both walls and ceiling. It was intended to be a magnificent riot of color, but now, age, dirt, and incense mean that everything is a monochromatic dark sort-of color. I think it would be marvelous if the temple could be restored to the builders’ original vision. I can’t imagine that those medieval architects, sculptors, and painters would be happy were they to see that sad, grim, dark interior, given that their original vision was so brilliant and dynamic.

Please note that the Japanese approach — to leave historic buildings and objects in their worn-out state is consistent with most art restoration outside of the Sainte-Chapelle. Moreover, please keep in mind that the Japanese cannot have a racial undertone to their decision about restoration’s role in art and architecture history. After all, Japan has had a monoculture, including a mono-race, for at least 1200 years.

Okay, with that point about the Japanese in mind, let me continue to make my point about art restoration:

Just this morning, when the mail came, I was glancing through this week’s The New Yorker, to which Mr. Bookworm subscribes. (As an aside about The New Yorker, when I started reading it many decades ago, its articles consisted almost entirely of gentle ruminations about subjects most magazines ignored. It was intellectual, without being too intellectual. It allowed a self-styled educated elite to get a glancing acquaintance with everything from art, to history, to science, to literature. By the 1990s, though, it was a dying magazine that Tina Brown revitalized by dragging it into pop culture. In the last 18 years, The New Yorker restyled itself again, this time as a bastion of upper class Leftism. It’s also a redoubt for climate change and all things racially-correct.) Now back to my point, from which I keep wandering.

In light of my ruminations about Japanese art restoration, I was instantly captivated by a new article: The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture – Greek and Roman statues were often painted, but assumptions about race and aesthetics have suppressed this truth. Now scholars are making a color correction. The author is Margaret Talbot, who has written in the last year weighty articles such as

- The Trump Administration’s Plan to Redefine Gender Recalls an Earlier Rejection of Science;

- Christine Blasey Ford’s Experience Was Just As Bad As Anita Hill’s — Maybe Worse;

- Scott Pruitt Is Gone, But The Trump Administration’s Climate Negligence Remains;

- The New Yorker Recommends: Loretta Lynn’s Plucky Ode to Birth Control;

- Scott Pruitt’s Dirty Politics;

- The Extraordinary Inclusiveness Of The March For Our Lives;

- Why It’s Become So Hard To Get An Abortion;

- Trump Makes The Global Gag Rule On Abortion Even Worse; and

- What Bill Clinton Should Do As First Gentleman (written a week before Bill Clinton did not become First Gentleman).

I hope I’ve successfully made the point that Talbot is a true believer of the hardest Progressive variety. One can assume, therefore, that race informs her world view — and, judging by her article about old statues, one would be right. Indeed, a give away is in the title: “The myth of whiteness.” On the one hand, it describes classical statutory as it appears in the early 21st century. On the other hand, “whiteness” is also the Progressives’ favorite nasty way of describing anything that doesn’t yield to the Progressive’s loathing for all things white. After all, in Trump’s America, even milk, because of its whiteness, is racist.

Talbot begins by discussing the undisputed fact that the art and restoration worlds resolutely refuse (for the most part) to allow modern people to see Greek and Roman statues as their creators meant them to be seen; that is, in dazzling color. As Vinzenz Brinkmann, one of the art experts Talbot interviewed for her article explained, “It turns out that vision is heavily subjective . . . You need to transform your eye into an objective tool in order to overcome this powerful imprint” — with that imprint being, as Talbot honestly states, “a tendency to equate whiteness with beauty, taste, and classical ideals, and to see color as alien, sensual, and garish.”

I think Talbot’s summation is correct: Our preference for white statutory is a class matter. The hoi polloi, the uneducated masses, the people fascinated by garish kitch, can’t appreciate the classics, most especially the classics’ white marble aesthetic purity. They are oafs, not educated aesthetes.

Had Talbot stopped there, she would have gotten buy-in from me but, true to her political beliefs, she couldn’t. Eventually, the article gets to the real point about our cultural preference (or, rather, the elites’ cultural preference) for shiny white statues. It’s racism, of course:

Lately, this obscure academic debate about ancient sculpture has taken on an unexpected moral and political urgency. Last year, a University of Iowa classics professor, Sarah Bond, published two essays, one in the online arts journal Hyperallergic and one in Forbes, arguing that it was time we all accepted that ancient sculpture was not pure white—and neither were the people of the ancient world. One false notion, she said, had reinforced the other. For classical scholars, it is a given that the Roman Empire—which, at its height, stretched from North Africa to Scotland—was ethnically diverse. In the Forbes essay, Bond notes, “Although Romans generally differentiated people on their cultural and ethnic background rather than the color of their skin, ancient sources do occasionally mention skin tone and artists tried to convey the color of their flesh.” Depictions of darker skin can be seen on ancient vases, in small terra-cotta figures, and in the Fayum portraits, a remarkable trove of naturalistic paintings from the imperial Roman province of Egypt, which are among the few paintings on wood that survive from that period. These near-life-size portraits, which were painted on funerary objects, present their subjects with an array of skin tones, from olive green to deep brown, testifying to a complex intermingling of Greek, Roman, and local Egyptian populations. (The Fayum portraits have been widely dispersed among museums.)

Do you know that I have never seen a Caucasian person who is as white as marble? I’m one of the most pale-skinned people you will ever meet and I’m still not white. If I were to lie in a snow bank, you would see me. As it turns out, even people who are classified as “dead white” are not “dead white” unless they’re actually dead. So it’s ridiculous to claim that people think the ancient Greeks and Romans were marble white.

The problem for Talbot (and Bond) is that a minute subset of white supremacist groups are laying claim to white statutory. For example, a neo-Nazi group called Identity Evropa has argued that the statues support white nationalism. What Talbot doesn’t mention is that Identity Evropa’s total membership, even according to the rabid SPLC, is only about 800 people nationwide. The group’s imprint on American popular culture is meaningless and its imprint on academic elite culture is even weaker than that.

After making that point, the article goes on . . . and on and on and on from there, with the elite art world striking back furiously against a handful of racist nobodies. I got bored and didn’t stick around to see if Talbot had anything else useful and practical to say about re-colorizing statues. After all, modern science does enable art restorers to find minute color particles on even the whitest statues so as to have a very good idea about the artist’s original color choices.

Because it’s late and I’m tired, I’ll end by going back to what I consider the real point here, the one Talbot abandons in her pursuit of racism: The people who created these sculptures had as part of their creative vision dazzlingly beautiful, bright colors. And indeed, it’s worth clicking over to the Talbot’s article just to see examples of color reconstructions. With those colors in mind, I firmly believe that art restoration should restore the art to the original artist’s vision, rather than keeping these masterworks in a faded, colorless limbo.