I don’t like Bernie because his “Medicare For All” plan is terrible for America’s health and economy

Bernie’s “Medicare for All” plan ignores facts: we can’t afford it, the European system floated on American money, and socialized medicine has bad outcomes.

This is a somewhat updated version of a post I wrote in February 2016, before the Hillary mafia got Bernie to retire from the fray. When I learned from my children about a polished, easy-to-consumer blog called I Like Bernie, But…, which was intended to allay fears about Bernie’s radical policies, I decided to create a counter-blog called I Don’t Like Bernie, Because….., and attacked him for his socialism, his tax plans, his anti-Second Amendment stance, and his socialized medicine plan.

Although I don’t think Bernie will be the Democrat nominee, the extraordinary weakness of the other candidates may mean that this wannabe tyrant somehow ends up as the last man standing. If that’s the case, I want to make sure my Bernie exposés are out there once again. Certainly the people behind I Like Bernie, But are hopeful that he’ll run again, for they’ve updated the website. It’s basic format is still the same, for its information is short, clear, and wrong. Today I’m tackling everything that’s wrong with Bernie’s plan to socialize American medicine.

The I Like Bernie site imagines a worried Progressive voter exclaiming “I heard he wants to get rid of Obamacare!” Not to worry , says I Like Bernie. In fact, Bernie wants to make Obamacare even better by putting our entire medical system into government hands:

This promise — that everyone will get high-quality, free medical care, thereby saving American families thousands of dollars a year, while keeping them healthier — is false. There is no way Bernie can do this. The numbers don’t add up, and both the Obamacare experience in America and the socialized medicine experience in Europe show that the free market, not government, is the only way to bring costs down, making quality medical care available to everyone. If you have the patience, this post will walk you through the analysis, using what I hope is clear, simple language, making learning about the economics of medical care a relatively painless process. (Or, as the doctor with the big needle aimed at your arm always says, “This won’t hurt a bit.”)

What Bernie promises

Bernie’s campaign, in its ongoing effort to pretend that Bernie is not a socialist (he is, and that’s a bad thing), has titled his plan “Medicare for all.” When he talks about his plan, though, Bernie skips that cute Medicare euphemism and goes for the kill — the government will be in charge of everything:

- Create a Medicare for All, single-payer, national health insurance program to provide everyone in America with comprehensive health care coverage, free at the point of service.

- No networks, no premiums, no deductibles, no copays, no surprise bills.

- Medicare coverage will be expanded and improved to include: include dental, hearing, vision, and home- and community-based long-term care, in-patient and out-patient services, mental health and substance abuse treatment, reproductive and maternity care, prescription drugs, and more.

Wait? You didn’t see the word “government” in the above quotation? Well, it’s there. You see the “single payer” to whom Bernie refers is the government. That’s a euphemism too. The government isn’t really paying for anything at all, because the government doesn’t have money of its own. It never earns money, it takes money. Thus, all of the money in its bank account is actually taken from every American who pays taxes.

So what Bernie really means when he talks about single-payer nationalized medicine is that he wants “taxpayer-funded” health care. He envisions using taxpayers to fund his grandiose plan of setting up a system in which the government takes those taxpayer funds and, after siphoning off vast funds for administrative salaries, waste, and graft, takes what’s left to pay for doctors, nurses, physician’s assistants, hospitals (everything from janitors to floor clerks to surgeons), dentists, optometrists, audiologists, home care providers, and pharmaceuticals. It will impose these fees from the top down, bullying doctors, dentists, and nurses who spent years, or even decades, perfecting their skills; hospitals that have invested millions in infrastructure to provide patient care; and pharmaceutical companies that routinely invest millions in research that usually comes up dry, in the hopes of hitting it big with the odd medicine here and there.

Here’s the truth: Even if you love Bernie’s plan, it can’t work. The numbers won’t add up, just as they haven’t been adding up in Europe or in America (with Obamacare). In the rest of this post, I’ll explain why. (Incidentally, the principles set out in this discussion apply with equal weight to all of the Democrats, each of whom promises, quickly or slowly, to implement socialized medicine in America.)

America cannot afford Bernie’s plan

Bernie promises that, by raising taxes on “the rich,” he can cover the costs for everything he promises, including putting the government entirely in control of doling out people’s money for medical care. I blogged here about the problems with Bernie’s general promise that “the rich” can pay for all of his plans, so I won’t repeat that discussion. Instead, I’ll just tell you here that they can’t. In this post, I’ll focus solely on Bernie’s scheme to fund a nationalized healthcare plan.

Bernie boasts that the plan will save middle class people thousands a year, but he’s playing word games when he says that. The reality is that, while middle class people will no longer have to write checks to their insurance company (assuming they don’t get insurance through their employer) or pay for deductibles and medicines, they’re still going to take a financial hit because taxes must go up significantly to fund his plan. Even under the most optimistic scenario (which we know never proves to be the case), middle class people will have to pay a lot of money if the system isn’t going to be running a multi-trillion deficit by the end of a decade.

During this campaign season, Bernie’s been cagey about details when it come to his plan. In April, though, he did release some bullet-point information offering a smorgasbord of plans that all involve draining the limited resources of the middle class and the rich:

- Creating a 4 percent income-based premium paid by employees, exempting the first $29,000 in income for a family of four

- Imposing a 7.5 percent income-based premium paid by employers, exempting the first $2 million in payroll

- Eliminating health tax expenditures

- Making the federal income tax more progressive, including a marginal tax rate of up to 70 percent on those making above $10 million

- Making the estate tax more progressive, including a 77 percent top rate on an inheritance above $1 billion

- Establishing a tax on extreme wealth

- Closing a tax-loophole that allows self-employed people to avoid paying certain taxes by creating an S corporation

- Imposing a fee on large financial institution

- Repealing corporate accounting gimmicks

Even the Bernie-friendly hard Left Vox outlet has a hard time envisioning how Bernie’s plan is going to work:

Financing the health care system that Sanders envisions is an immense challenge. About half of the countries that attempt to build single-payer systems fail. That’s Harvard health economist William Hsiao’s estimate after working with about 10 governments in the past two decades. Whether he is in Taiwan, Cyprus, or Vermont, the process is roughly the same: Meet with legislators, draw up a plan, write legislation. Only half of those bills actually become law. The part where it collapses is, inevitably, when the country has to pay for it.

This is what happened when Sanders’s home state of Vermont attempted to create a single-payer plan in 2014. Much like Sanders, local legislators outlined a clear vision of the type of health plan they’d want to extend to all Vermonters. Their plan was arguably less ambitious; it did require patients to pay money when they went to the doctor.

But Vermont’s single-payer dream fell apart when the state figured out how much it would need to raise taxes to finance its new system. Vermont abandoned the government-run plan after finding it would need to increase payroll taxes by 11.5 percent and income tax by 9 percent.

Even if one assumes that Bernie was able to push through some sort of a plan (kind of like Obama pushed through Obamacare), it’s not going to work. What will really happen is that the healthcare system will become another huge, unfunded liability, while chronically sucking wealth out of the American economy. This Daily Caller analysis is as true today as it was when written in 2016:

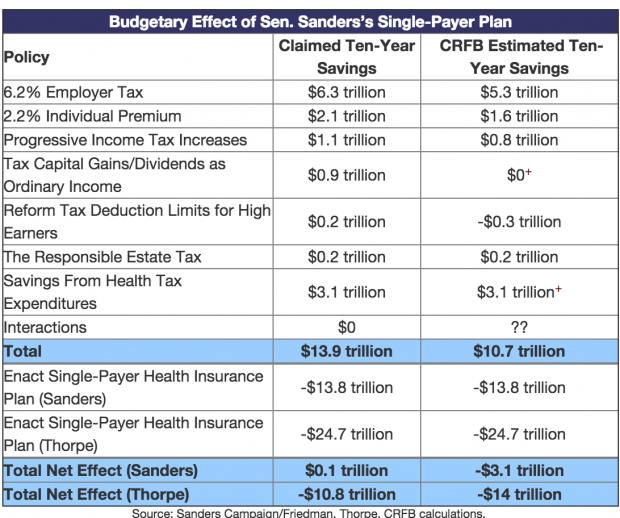

An analysis of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ single-payer health-care plan released Wednesday reveals that despite significant tax increases, it would add between $3-$14 trillion to the federal deficit over 10 years, while giving the United States the highest capital gains tax rate in the developed world.

It would also raise the top tax rate to 85 percent, according to the analysis by the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Sanders proposed what he calls a “Medicare for all” plan, which his campaign estimates would cost an additional $1.4 trillion per year. It would be financed by six separate tax increases. The CRFB found, though, that the tax hikes would not be enough to cover the program’s cost, and that it would add $3.1 trillion to the federal deficit over 10 years.

[snip]

The campaign estimates that replacing the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), personal exemption phaseout (PEP), and Pease limitation with a 28 percent limit on deductions would result in a revenues of $150 billion over 10 years. The CRFB finds that in fact this would lose the federal government $250 billion. Sanders’ campaign believes his proposed employer payroll tax and income surtax would provide $8.4 trillion over 10 years. Though using CBO estimates of what those taxes would bring in revenues, the CRFB found that it would more likely be less than $7 trillion in revenue over a decade.

Many of these changes also would also have negative macro-economic effects that would be difficult to project. For example, Bernie’s plan to tax capital gains and dividends as ordinary income would have a top rate of 62 percent (52 percent from income, 6.2 percent from his Social Security plan, and 3.8 percent from a Medicare investment surtax).

You can read more of that article here. If you’re a numbers person, you can also study this handy-dandy chart, from the same article:

A three-trillion-dollar deficit over ten years, just for healthcare costs, is a very big deal.

Oh! And if you’re a young person reading this, there’s one more thing you need to know: You’re going to be the one paying for this nationalized healthcare, although it’s not clear whether you’ll ever see a real benefit from it.

Imagine that the US already has socialized medicine. Now think about yourself as compared to your grandparents: You are as healthy as a horse and almost never see a doctor. Your grandparents, however, often need to see doctors for a variety of health problems that become more common as the human body ages. Logically, then, your grandparents, along with everyone else’s grandparents, are going to receive the greater part of the healthcare provided in America.

Here’s one other thing you need to think about in connection with your grandparents: They’re retired, which means they’re not earning money and are therefore no longer paying income taxes. America already has a huge debt, so there’s no extra money lying around to pay for Bernie’s plan. What this means is that, as future government spending piles up, even as your grandparents take more from the system, they won’t be generating any future wealth to offset their usage. You, on the other hand, are entering your peak working years, making your generation the government’s cash cow for income taxes. You will be paying a lot of money into a system that you are not using.

Under this scenario, you have to hope that the generation behind you also works hard and pays money into the system, and that the same holds true for several subsequent generations. Otherwise, when it’s your turn, you may find that the system is running on empty — which is precisely what has happened already with Social Security and Medicare. Nor will this problem of the takers not paying and the payers not taking go way any time soon. Because Americans are living longer, the crowd at the top, the old people demanding medicine but not paying taxes, keeps getting bigger.

In other words, when it comes to nationalized health care with a vast and growing elderly population, a “pay it forward plan” is a high-risk, low-reward deal for the young ones doing the paying. In other words, what Bernie is proposing is nothing more than a giant Ponzi scheme. This is a scheme that promises investors huge returns but, in fact, creates no wealth. Instead, early investors receive money paid in by later investors. Eventually, of course, you run out of new investors to pay off the old ones. At this point, the whole scheme collapses.

Progressive claims to the contrary, European health care not the wonderful thing that you think it is

I don’t have to be in the room with you to know what you’re yelling now at the computer screen: “What about Europe?! Socialized medicine has worked in Europe.” I’m sorry to break this to you, but it hasn’t — or, at least, it hasn’t worked as you think it has.

When talking about European socialized medicine, there are two things to consider: Whether the system can be funded and whether the people living under the system get quality care? I’ll deal first with funding, and then second with the care Europeans receive.

The socialized medicine system in continental Europe starts with the end of World War II. After WWII ended, large parts of Western Europe were completely flattened. The infrastructure was gone, six years of war having effectively bombed Europe back to something shortly after the Stone Ages. Eastern Europe, of course, was starting its long darkness under Soviet Communist rule.

The anti-Communist United States was quite worried that, given the destruction in Western Europe, the Soviets could easily expand their sphere of influence into the West. The United States therefore embarked up the “Marshall Plan” to rebuild Europe. Europeans neither had to earn nor repay the money that America handed over; it was a gift to get Europe back on its feet, both for humanitarian reasons and so that it would resist communism. When Europe industry started rolling again, it had very little debt to repay. the Marshall Plan was like an industrial head start or, to use a sports metaphor, a big golf handicap.

In addition to cash handouts, the United States gave Europe another big gift: It took on most of Europe’s defense costs during the Cold War. The various nations certainly had their own armies, but these armies were small and usually contributed only a minimal amount to the hot wars that broke out during the Cold War. As those of you who are anti-war know, it’s expensive to have a military. European nations did not have to bear that expense, or they bore a minimal, almost ceremonial defense burden.

With the money Europe didn’t pay for capital expenditures, that it did not pay on repaying loans for infrastructure development, and that, for decades, it did not pay for defense, Europe ended up having room in its budget for healthcare. In other words, even as Americans were paying out-of-pocket for their own health care, their tax dollars were also being used to help fund Europe’s “socialized” medicine.

It’s certainly true that Europeans also paid for the own healthcare through extremely high taxes. These high tax rates worked well when European countries, which are all smaller than America, had homogeneous populations. That is, almost everyone in these countries had shared values that included a willingness to pay into the system when young based upon the belief that, when a specific generation of young people stepped up to old age, the next generation of young people would take on the burden of working and paying for the system. It was all very fair and very sweet.

But here’s something you may not know about socialized countries: The people in them don’t have babies. After the post-war baby boom ended in the early 1960s, European adults began to have fewer and fewer children. Europe now has a negative growth rate, meaning that it’s not having enough babies to replace the old people who age expensively and then, once they reach ripe old ages, finally die. The youthful population is shrinking, while the bulk of the population keeps aging.

Let me remind you about what I said above: a “pay it forward” medical system doesn’t work when the bulk of the users are too old to pay into it, even as the number of young people paying into it keeps shrinking. You can imagine that this puts great financial stress on the system. The stress is worse because the end of the Cold War meant serious diminution in American dollars funding the military, which had for decades freed up European cash for health care.

Looking at Germany’s shrinking youth population, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made the fateful decision to stem the financial losses resulting from a vanishing working-age population by welcoming in hundreds of thousands of Middle Eastern and North African immigrants, almost all of whom were young. On paper, it looks like a fine idea: If your working population is vanishing, import a new one.

What Merkel forgot is that a primary element behind European socialism’s success was a small, educated, homogeneous population that played by the rules. The new immigrants weren’t raised in that belief system. In addition to being largely illiterate, the new immigrants operate under a “I’ll take everything I can now, while I can” world view. Their Muslim faith adds an additional psychological element, which is the doctrinal belief that non-Muslim populations rightly should support Muslims. So instead of paying into the system like good native-born Europeans, the new immigrants are taking even more out of the system, raising the stress level.

This immigrant trend has been taking place for some time now, as Europe started decades ago opening its doors to people from the Middle East and North Africa in order to replace its decreasing population growth. At a slow trickle, Europe could adjust somewhat to accommodate the stress on the healthcare system, both in terms of funds and infrastructure. With millions of people banging on Europe’s doors, though, it’s very doubtful that the system can hold out indefinitely.

In sum, socialized medicine in Europe was a functioning program for a few decades only because of a unique set of circumstances: Lots of American money, no major defense costs, a post-war baby boom, and a homogeneous population with shared values. Take away any one of those factors, and socialized medicine starts having financial troubles. Take away all of those factors and socialized medicine will swiftly come to the end of the line.

In addition to being unaffordable absent extraordinary circumstances (which are not present in America), Europe’s medical care isn’t now and never was that good. Yeah, yeah, I know you’re shocked to hear that. After all, back in 2000, the World Health Organization (“WHO”) came out with a report that savaged the American healthcare system when compared to Europe.

The WHO report concluded that, on overall performance, the world’s richest and most powerful nation managed to rank at only 37th place when providing overall healthcare. Here’s the thing: You should never rely on a study’s conclusions unless you know the metrics that controlled the study’s outcome.

When Americans think of healthcare, they think of speedy access and good results: They might say, “My grandmother got a new hip within two weeks of the doctor saying she needed one,” or “my father’s cancer has been in complete remission for 10 years,” or “I was hospitalized immediately when I got pneumonia,” or “I can almost always see my doctor within two days after I call” . . . that kind of thing. Thus, when Americans hear about a presumably reputable study stating that America is only in 37th place when it comes to quality medical care, they think this means that, their own experiences notwithstanding, for everyone else the new hip never happened, the cancer killed someone, the pneumonia also killed someone, and the doctor’s wait-list was months long (all of which was true for the VA, before it got overhauled, which was the only example of truly socialized medicine we have here in America).

Putting aside the VA’s sad history, the reality is that the WHO report got it all wrong about American medicine. You see, WHO wasn’t interested in the things that matter to Americans when they think about quality treatment: namely, outcomes and wait times. WHO’s metric was whether medicine was socialized or not. The more socialization, the higher the scores, regardless of outcome.

Scott Atlas, in a great article entitled “The Worst Study Ever?” took the time to break out the numbers:

World Health Report 2000 was an intellectual fraud of historic consequence—a profoundly deceptive document that is only marginally a measure of health-care performance at all. The report’s true achievement was to rank countries according to their alignment with a specific political and economic ideal—socialized medicine—and then claim it was an objective measure of “quality.”

[snip]

Before WHO released the study, it was commonly accepted that health care in countries with socialized medicine was problematic. But the study showed that countries with nationally centralized health-care systems were the world’s best. As Vincente Navarro noted in 2000 in the highly respected Lancet, countries like Spain and Italy “rarely were considered models of efficiency or effectiveness before” the WHO report. Polls had shown, in fact, that Italy’s citizens were more displeased with their health care than were citizens of any other major European country; the second worst was Spain. But in World Health Report 2000, Italy and Spain were ranked #2 and #7 in the global list of best overall providers.

Most studies of global health care before it concentrated on health-care outcomes. But that was not the approach of the WHO report. It sought not to measure performance but something else. “In the past decade or so there has been a gradual shift of vision towards what WHO calls the ‘new universalism,’” WHO authors wrote, “respecting the ethical principle that it may be necessary and efficient to ration services.”

[snip]

The nature of the enterprise came more fully into view with WHO’s introduction and explanation of the five weighted factors that made up its index. Those factors are “Health Level,” which made up 25 percent of “overall care”; “Health Distribution,” which made up another 25 percent; “Responsiveness,” accounting for 12.5 percent; “Responsiveness Distribution,” at 12.5 percent; and “Financial Fairness,” at 25 percent.

The definitions of each factor reveal the ways in which scientific objectivity was a secondary consideration at best. What is “Responsiveness,” for example? WHO defined it in part by calculating a nation’s “respect for persons.” How could it possibly quantify such a subjective notion? It did so through calculations of even more vague subconditions—“respect for dignity,” “confidentiality,” and “autonomy.”

That’s just a small portion of a superb article. I urge you to read the whole thing.

As another example of the GIGO (Garbage In-Garbage Out) factor when it comes to comparing American medicine to medicine in other parts of the world, perhaps you’d like to know why high school and college textbooks keep saying that rich, powerful America comes in at a dismal 54th place for infant mortality.

What the textbook authors don’t know, or ignore, is that, when it comes to calculating infant mortality rates, different countries have different ways of determining what’s a “live birth.” America is one of the few countries in the world that counts any baby born alive, no matter how fragile it is, as a living baby for infant mortality purposes.

In other countries, including Europe and Asia, the public records count as a “live birth” only babies that are a certain minimum size or weight, or that have already survived a certain amount of time outside of the mother. This means that comparing U.S. numbers with other countries’ numbers is an apples and oranges comparison unless you adjust for the differing baseline of what constitutes a live birth. Any study that ranks America so low on infant mortality is based upon a flawed comparison of unequal data. What we really should be ranked upon — and ranked very highly — is the value we give to every life, no matter how fragile.

Remember that, as Mark Twain or Disraeli (or someone else) said, there are lies, damn lies, and statistics.

The reality is that America has very good medical outcomes and that people have long had swift access to quality medical care. Moreover, because there is lots of money flowing through the system (rather than clutched in a government bureaucrat’s fists), businesses have an incentive to invest in researching new medicines or coming up with new techniques.

Money, after all, is a fabulous motivator. Lack of money leaves you in the situation of my aunt, a fervent communist who lived out her days in East Germany. In her “upscale” party-member apartment, her kitchen sink was broken — and had been broken for nine years. “Never mind,” said Auntie Marxist. “I’m on the list for a government plumber to come and fix it.” So far as I know, she was still on the list with that broken sink a decade later when she died.

Underlying that perverse WHO study is the reality that the government is ultimately more concerned with the bottom line than it is with any individual. When push comes to shove, you’ll make financial sacrifices to save your parent’s or child’s life. Government doesn’t care. It doesn’t love you. You’re a statistic.

This ugly reality has revealed itself in England, which has for some time been relying heavily on healthcare rationing to make up for missing money in a system that’s breaking down for the reasons I described above. By the way, in addition to diminishing funds, lack of competition worsens the situation. If patients are being killed in Hospital A because of that hospital’s penny-pinching ways, they have no option to go to Hospital B, that will treat them better. In England, they’re all Hospital A.

And that’s how you end up with stories about the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. Isn’t that a nice name? Rather than forcing painful and ultimately unhelpful medical procedures on people who are near death, let them go peacefully, with just palliative (comfort) care.

The problem was that people were taking too long to die, so many National Health Care hospitals refined the Pathway’s definition of what constitutes “near death.” The resulting scandal revealed reports of hundreds, even thousands, of elderly patients who were not at death’s door, but who were nevertheless hastened to their deaths, starving, dehydrated, and abandoned.

The highest level of the British government’s supports the cold, hard calculation that old people in England, who are no longer paying money into the system, are a burden on socialized medicine. Just a few years ago, a senior government adviser said that the National Health Service should save money by killing people with dementia on the ground that old and sick people have a duty to die (emphasis added):

Elderly people suffering from dementia should consider ending their lives because they are a burden on the NHS and their families, according to the influential medical ethics expert Baroness Warnock.

The veteran Government adviser said pensioners in mental decline are “wasting people’s lives” because of the care they require and should be allowed to opt for euthanasia even if they are not in pain.

She insisted there was “nothing wrong” with people being helped to die for the sake of their loved ones or society.

The 84-year-old added that she hoped people will soon be “licensed to put others down” if they are unable to look after themselves.

[snip]

Lady Warnock, a former headmistress who went on to become Britain’s leading moral philosopher, chaired a landmark Government committee in the 1980s that established the law on fertility treatment and embryo research.

Your takeaway from this should be that the government doesn’t love you; it loves its statistics and five-year goals. When the money runs out, don’t be surprised if the government isn’t knocking on the door of your hospital room to let you know that your life is too expensive and must end. Those old people in England were the ones who funded that National Health Care service for decades. They believed in it. They trusted their government. And it killed them anyway.

Knowing all that, are you really willing to put your life in the hands of government bureaucrats?

The free market is the best way to bring healthcare quality up and prices down

The absolute best way to ensure top flight care and affordable prices is through the free market. And before you start saying “That didn’t work in America, which is why we needed Obamacare,” you need to understand that America hasn’t had a free market since WWII. It was then that the government placed salary caps on employers in a misguided effort to help fund the war effort. Prevented from giving high salaries to entice the best workers, employers began offering health insurance benefits as part of the salary package. This disconnected people from both the cost of insurance and the cost of medical care.

Employer provided health insurance is a lousy way to keep costs down. The insurance companies try to do it by stiffing doctors or hospitals, or denying insureds payment. That’s inefficient. The best way to control costs is to have patients shop around in a competitive market. If my insurance company is paying, it doesn’t matter to me whether my child gets her checkup by a reputable doctor who charges $60 or a reputable doctor who charges $80. It matters only if I pay that money. For basic medical care, the patient should be the first line of defense in cost control. To that end, President Trump is trying to make cost comparisons easier by forcing hospitals to break down and reveal costs (and maybe explain that $200 aspirin).

Incidentally, if individuals, not employers, purchased most health insurance, that would also control insurance costs. Even before the rigid complexities of Obamacare, individual healthcare also wasn’t really a free market. In California, insurers have hundreds of regulations that drive costs up, something that’s not the case in, say, Texas. Insurance companies also can’t compete across state lines, so consumers may be trapped in very expensive markets. Also, mandates about what insurance most offer mean blocking a free market that would allow a healthy young man to make a minimal payment for catastrophic insurance, while parents with young children could pay for a more complete plan to cover all the things that can go wrong with little kids. As it is, our current system makes everyone, including really old people, pay for fertility treatments.

By the way, if you’re worried about people with chronic conditions who often ended up uninsured before Obamacare, the marketplace could have helped that too. Just as everyone who buys car insurance knows that some portion of that insurance fee is going to cover uninsured motorists, a similar system could be established to enable poor risk patients to get insurance. When it comes to people who cannot afford insurance or have been denied it because of chronic conditions, a slight mark-up to create a fund for premiums in the free market is a hell of a lot easier than turning the entire healthcare system over to the government.

If you doubt me about the benefits of competition, dig into your desk drawer and drag out one of your flash drives. Take a good look at that useful little thing and think about this: On Amazon today, you can get ten 32 GB flash drives for $34.00 — or $3.40 per flash drive. What you probably don’t know if you’re under 35 is that, when flash drives first came out in the 1990s, their storage ability was measured by megabytes, not gigabytes, and their cost was in the hundreds of dollars. What brought quality up and costs down was competition, unimpeded by government mandates and other market perversions.

Conclusion

There is no such thing as a free ride. Absent a rich country funding your socialized medicine, a completely homogeneous population willing to play by the rules, and young adults who are constantly having more children who will also play by the rules, your socialized medicine system will always go broke.

America can’t look to another country willing to pay the costs and cannot count on a constantly burgeoning population of young people willing to pay it forward in exchange for an unreliable promise that they’ll get some care too. Indeed, we have an example of that problem right here at home: Almost within minutes of its creation, Obamacare started hemorrhaging money because old people use it but don’t pay for it, and young people don’t use it and are unwilling to pay for it.

In addition, wherever there is socialized medicine, there is bad care. Bureaucrats who face no competition are not interested in the quality of care. They’re interested in metrics such as the number of patients registered with a hospital (whether or not they get treated) or the best way to make the numbers about baby deaths look good (e.g., refusing to count fragile babies as “live births”).

So next time you hear someone say Bernie or any other Democrat candidate will improve American medical care by handing it over to the government, ask yourself — and your friend — whether there isn’t a better way.

(You can see the other posts in this series here, here, and here.)

Image credit: Detail of Bernie Sanders by Matt Johnson.