Growing up American

I recall a time when public education and the entertainment world helped forge a common American culture undefined by race or sexuality.

I don’t think I’ve made any secret of the fact that I don’t “get” baseball. I understand it technically, of course. It’s just that I don’t understand why people enjoy it.

When I mentioned that as part of a bigger discussion with a friend, he said, “I don’t think that’s at all surprising considering your European upbringing.”

I knew instantly what he meant despite the fact that I was born and raised in America. My parents came from Europe and never embraced America. Although we spoke only English in the house (hence, my embarrassing inability to speak any languages other than English), there was nothing American in my home: the aesthetics, the food, and the values were all tied very tightly to the old country. Getting back to baseball, even American football, baseball, and basketball were derided (although we did like the Harlem Globetrotters).

Meanwhile, at school, all my friends were first-generation Asians. That is, like me, their parents came from another country. They too grew up in houses that had little to do with America.

In theory, we children should have revolved endlessly in lonely little circles and become emotionally and practically disassociated from America. We didn’t, though. We still had American anchors.

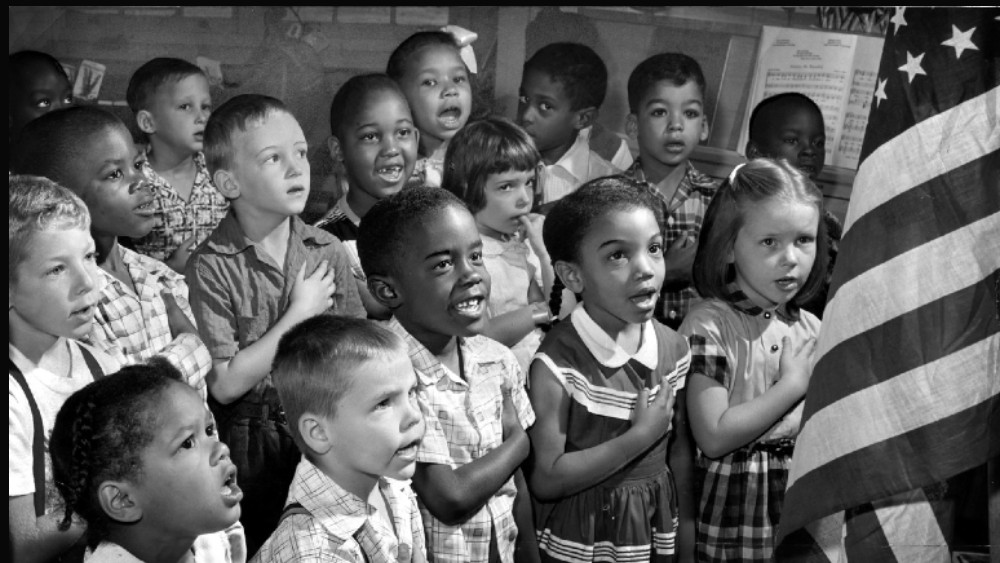

Some of those anchors came from our schools. Whether Jewish, Muslim, Atheist, Buddhist, or Christian, we all came together to sing the same Christmas songs, both secular and religious. We all recited the Pledge of Allegiance and, enthusiastically if tunelessly, sang the Star-Bangled Banner. We took our required Civics classes, all of which were boring but still praised the genius of the American founding and its form of government.

In high school, while there were Jewish clubs, Russian clubs, Chinese clubs, Filipino clubs, Samoan clubs, German clubs, and Black clubs, those clubs were subsets of our larger American identities. They mostly revolved around language, food and, sometimes, dancing. They certainly didn’t define who we were (that is, if you were in the German club, that did not mean you had abandoned your American identity) nor did they preclude us from engaging with others.

The other anchor for all of us was entertainment. Before the entertainment industries fragmented and became invested in appealing to discrete demographics, we all listened to the same music and watched the same TV shows and movies.

I remember debating with friends of all races which of the Brady boys was the cutest. (The general consensus was that Peter was the cutest, Marcia was cool, and Jan was a dweeb.) When Good Times came along, we all watched it, laughed, and learned. I’ve never forgotten the episode that informed us that Black children got marked down on standardized language tests because they struggled with this multiple choice question:

Cup and

1. Chair

2. Table

3. Plate

4. Saucer

According to the show, Blacks didn’t use saucers. If they weren’t up on their reading, the kids assumed the phrase was “cup and table.” Was that tidbit of info accurate? I have no idea but it deeply impressed me. We also went around saying “Dyno-mite” to each other all the time. When Mork came along, we switched to “Nanoo-nanoo.”

Incidentally, did you know that Jimmie Walker, who played James “J.J.” Evans, Jr., was (and maybe still is) best friends with Ann Coulter? Apparently, both of them took seriously the 1970s idea that, while some Blacks and some Whites had different cultural experiences, they could still socialize.

The fact that funk and disco were part of the Top 40 — and, of course, we all listened to Casey Kasem’s weekend countdown of the top 40 songs in America — meant that we had a common musical culture too. Again, there were debates (ABBA or Earth, Wind & Fire? I happened to like both but others weren’t so ecumenical) but we all knew the same things.

I could go on indefinitely reciting the pop culture that controlled my childhood but I’ll put the kybosh on this trip down memory lane. Suffice to say that, with three network channels, PBS, and a handful of local channels, even though I attended very multicultural schools (especially because of busing) we were all in the same cultural corral.

Was it stifling? Maybe. Probably. But the fact was that this stifling environment ensured that we had a common culture and, moreover, one that was not defined by race, color, creed, country of national origin, sex, etc. No matter how divorced from American culture our general home lives were, as long as we watched TV and went to school, we were Americans. In addition, none of those venues insulted being American.

Sure, as Ben Shapiro wrote in Primetime Propaganda, leftists were already then using entertainment to change American values — but they hadn’t yet started insulting America. Moreover, they were vehemently, regularly, and aggressively asserting Martin Luther King’s (and Jesus’s) view of race: The color of our skin mattered infinitely less than the content of our character.

As they’ve aged, many of my high school classmates have fallen away from that model. Looking over their Facebook posts, the biggest indicators of whether people would abandon the notion of a shared culture and people being judged by their character were whether they were gay or Jewish. All of my gay high school classmates are to the left of left. With one exception, all of my Jewish classmates are also lefties. (As for that one Jewish holdout, he’s a stalwart conservative who made Aliyah.) In other words, both gays and Jews embraced the left’s tribalism in lieu of being American.

It was a good experiment while it lasted. I had a difficult childhood because I was a nerd among nerds and a geek among geeks. I also wasn’t very nice, because I learned sarcasm and condescension at home, always hit back first (verbally, not physically), and am not inherently a very nice person. But I can say with absolute certainty that my life as a social oddity never had anything to do with today’s obsessions about race and sexual orientation.

IMAGE: Baltimore schoolchildren saluting the flag in 1955. Photo from Baltimore Civil Rights Heritage, which defines its site as a CC BY 4.0 site.