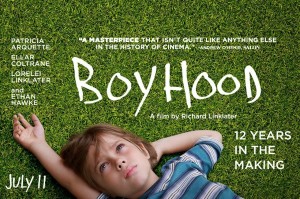

Movie Review: “Boyhood” — a celebration of depressive dysfunction in a clever package

Boyhood, which opened in July 2014 and is currently slated as one of the top contenders for Best Picture, has earned that rarest of rare accolades: a 100% score on Metacritic. Critics just love the movie.

Boyhood, which opened in July 2014 and is currently slated as one of the top contenders for Best Picture, has earned that rarest of rare accolades: a 100% score on Metacritic. Critics just love the movie.

The most obvious thing they love about the movie is the movie’s gimmick, which is actually quite clever. The movie was filmed over the course of 12 years, with the same actors gathering together for a few days each year to shoot that year’s scenes. It’s seamlessly edited, so you see the children grow up and the parents grow old. In that way, it’s like watching a very well-produced montage of home movies. Small wonder that probably 75% of each of the reviews I read centers on this clever technique.

Gimmicks alone, however, are not enough to sustain a 100% score created by looking at 49 different critic reviews. The critics also really like the movie’s story arc and character development. [If you’re planning on seeing the movie, you might want to stop right about now, because I’m going to go into SPOILER territory.]

Giving you time to think about whether you want to continue. . . .

Tick. . . .

A little more thinking time. . . .

Tock. . . .

Okay, last chance. After this sentence, a review filled with SPOILERS is about to begin. . . .

The plot of Boyhood is a simple one. The boy, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), lives with his mother, Olivia (Patricia Arquette), and his sister, Samantha (Lorelei Linklater, the filmmaker’s daughter). The children’s father, Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke), makes regular visits throughout the movie’s 12 year time span.

In those 12 years, Olivia goes from being a single, divorced mom who dates men who resent her children (and can’t act); to marrying a college professor with two children; to being the emotionally and physically abused wife of the same wildly alcoholic college professor; to being a single mom again; to being the slightly browbeaten girlfriend of a veteran who drinks to much and expects her son to follow house rules; and finally to being the despairing, single 41-year-old mother of two college students, who’s now living alone in a small apartment thinking her life is over. Through this same trajectory, she goes from being a high school grad with no work prospects, to being a college professor in psychology.

Arquette’s delivery reminded me of Robin Wright’s delivery in House of Cards. But while Wright manages to sound sinister and calculating, Arquette cycles endlessly between depressed, worried, and angry. Yeah, I get that it’s tough being a single Mom, but almost three hours of her was painful.

In the same 12 years, Mason Sr. goes from being an Obama-loving goof-off who has his children steal McCain lawn signs; to being an actuary; to being a suit-wearing husband to his second wife; and father of their little boy. The second wife’s parents are very nice gun-shooting Bible-thumpers. Mason Sr. ridicules them. Mason Sr. loves his kids as only a narcissist can. Hawke’s portrayal is as hyperkinetic as Arquettes is low key to the point of terminal depression.

The children try to cope with all of the moves and men that come their way. They fight with each other a lot (something I don’t need to see in a movie, because I get it at home). Samantha is a snarky teen who drinks too much by the time she’s in college. When she’s not fighting, Linklater’s affect too is as flat and depressed as Arquette’s.

Mason Jr., the ostensible focus of the movie, has both Linklater and Arquette beat when it comes to flat affect, tempered with the occasional nasal whine. There were times during the movie when I wanted to call a halt to it so as to check his pulse and make sure it was still there. By the end of the movie, he’s heroin-chic thin, drinks too much, has high school-aged sex, smokes pot, and happily accepts hallucinogenic mushrooms from a college roommate he’s met moments before, before going off on the stereotypical “howl at the sky while in a Southwestern landscape” hallucinogenic trek. My daughter, thank God, thought he was disgusting.

Indeed, everyone in this movie was distasteful. The Mom was always angry and hopped from bad man to bad man before deciding, at 41, that her life is over. The dad was loser who ostensibly became an accountant, but never reminded me of anything more than a generic Hollywood hustler character. Even in a suit with a new baby in his arms, you expected that he would try to sell you shoes that had just fallen off the back of a truck. The girl, as I said, was a boring, stereotypical teen who matured into depressed drinker. And the boy, as I said, was what my teens described as “Emo” — meaning all angsty, drinky, and druggy. My son, who watched for about ten minutes, said he was “gross.” My daughter, who watched the second half, summed his character up by saying “Even the dumbest kids at my school are smarter and more interesting than this guy.”

And with that comment about being interesting, my daughter hit upon another problem with the movie: the dialogue, some of which was apparently ad libbed, is incredibly boring. I like interesting people and, thankfully, find that most of the people in my world are interesting. Apparently none of them were around when Boyhood was being written or filmed. The people in the movie, one and all, are staggeringly dull. Their conversational boundaries are fighting with each other, making stale everyday observations, and coming out with trite banalities — with all but Hawke’s manic, yet surprisingly dull, rants delivered in flat, affectless tones. Even the guy who doesn’t like Obama — an old white guy with a Confederate flag who threatens to shoot the children for knocking on his door asking if they can put up an Obama sign — sounds as interested in what he’s saying as that bored clerk you just talked to at the Post Office.

But that’s not what the critics saw. The Washington Post review expresses gratitude that Mason Jr. has been appropriately feminized:

By the time Mason, now a deep-voiced teenager, affects an earring, blue nail polish and an artistic interest in photography, viewers get the feeling that he’s dodged at least most of the misogynist conditioning of a boy’s life.

NPR is proud of the adult Mason — the drinking, drugging, draggy, and pathetic emo Mason:

The picture is so unassuming and understated as it wends its way through a dozen years in the life of this family — in all our lives, really — that you’re likely to be surprised at how invested you feel — how proud and conflicted — when Mason finally stands on the brink of adulthood.

The Boston Globe sees Mason Jr., the drug-using, whiny Emo dude, as the flinty descendant of the all-American characters Gary Cooper used to play:

An observer by nature, Mason grows into a mellow kind of rebel who nevertheless shows flinty resolve. He’s a true American type — the morally grounded individualist — and at times toward the end you could swear you were watching Gary Cooper with gauges.

At the San Francisco Comical, the review raves about Coltrane’s acting chops and moral clarity as he tells his over-21 mother. who had a glass of wine, that he, an underaged 15-year-old, is stoned:

As for the boy, Ellar Coltrane … well, Linklater got lucky. The kid can act. He also has a rare poise, which you can see start to emerge when he’s 12. When he’s a teenager, there’s a memorable moment in which he comes home and his mother asks if he’s been drinking. He says yes. She asks if he’s been smoking pot. He says yes. She looks at him with amused appreciation – a kid who’s not afraid to tell the truth.

Yeah, acting chops: A flat-affected teen admitting to being stoned. And yeah, moral courage insofar as he tell his adult mother that his underage, illegal drug use is precisely the same as her having a glass of wine.

Of all the reviews I read, only Peter Rainer, at the Christian Science Monitor, seemed to have a glimmer of insight into the fact that this movie is all gimmick, with little substance. After raving about the fact that the actors really age, rather than just getting made-up to look older or, in the case of the kids, having different actors substitute in, he admits that large stretches of this 2 hour 45 minute reel are just boring:

Linklater’s risks in this film are as much aesthetic as practical, and occasionally they don’t pay off. Sometimes banal is just banal. There are boring stretches during which I would have welcomed a little Hollywood hoo-ha.

I’m betting that this movie will take best picture. It’s got everything Hollywood likes: a well-done gimmick and a story line that presents the “successful” American family as one plagued by divorce, violence, and instability; ordinary teen-aged girls as the ones who drink and sleep around (but who don’t get pregnant); and successful boys as the ones who are effete, drug-using, artistic depressives.

If it were me, I would give this movie an A+ for gimmick, and a C- for content and acting. It was a three hour waste of my life, given value only by the fact that it became fodder for this post.