The dangerous Progressive illusion that government makes us safer

One of my favorite expressions is “moral hazard.” I know you’re thinking that this term describes the risk of exposing innocent children to pot-smoking prostitutes, but it actually refers to a very different topic.

One of my favorite expressions is “moral hazard.” I know you’re thinking that this term describes the risk of exposing innocent children to pot-smoking prostitutes, but it actually refers to a very different topic.

I first came across the term “moral hazard” in a Commentary Magazine article by James K. Glassman, who was then arguing against the promises in the as-yet-unpassed Obamacare. (Depending on the number of Commentary Magazine articles you’ve read lately, this might be behind a pay-wall.) Here’s Glassman’s quick-and-dirty definition:

When someone insures you against the consequences of a nasty event, oddly enough, he raises the incentives for you to behave in a way that will cause the event. So if your diamond ring is insured for $50,000, you are more likely to leave it out of the safe. Economists call this phenomenon “moral hazard,” and if you look around, you will see it everywhere. “With automobile collision insurance, for example, one is more likely to venture forth on an icy night,” writes Harvard economist Richard Zeckhauser. “Federal deposit insurance made S&Ls more willing to take on risky loans. Federally subsidized flood insurance encourages citizens to build homes on flood plains.”

We all intuitively recognize the truth behind moral hazard. When we’re driving in a car so safe it’s the passenger equivalent of an armored car, we take more risks in terms of speed and lane changes than we would in a tinny old Ford. Even as we crow about being less vulnerable to injury, we’re suddenly more likely to cause a crash. And here’s the problem: while a sturdy Volvo may well protect us against a fender bender, the fact remains that, once you’re in a crash, all bets are off regarding the likelihood of injury or death. Crashing at 90 miles per hour in your safe car is as likely to kill you cause, or even more likely to do so, than a 40 mile crash in your Mom’s 1984 Toyota.

Despite this reality — despite the fact that we take incredibly dangerous risks if we think we’re somehow “off the hook” for consequences — DemProgs persist in believing that it’s possible to legislate the world into perfect, government-approved safety. I’ve had a taste of this in my own home although, thankfully, without any consequences more negative than irritation and some possible hearing loss.

When we bought our house, it came complete with a swimming pool that was already old and decrepit when we moved in. We nevertheless managed to keep it going for more than a decade until, finally, the pool gave up the ghost. It was time for a re-do.

As part of the re-do, we were required to obtain a permit from our local town and, of course, to comply with code-mandated safety requirements. The requirements aren’t just against hazards that the ordinary user cannot protect against, such as electrocution from improperly grounded wires, but are also intended to protect children from drowning. As every pro-gun rights activist knows, drowning is among the top accidental child-killers in the U.S.:

Every day, about ten people die from unintentional drowning. Of these, two are children aged 14 or younger. Drowning ranks fifth among the leading causes of unintentional injury death in the United States.

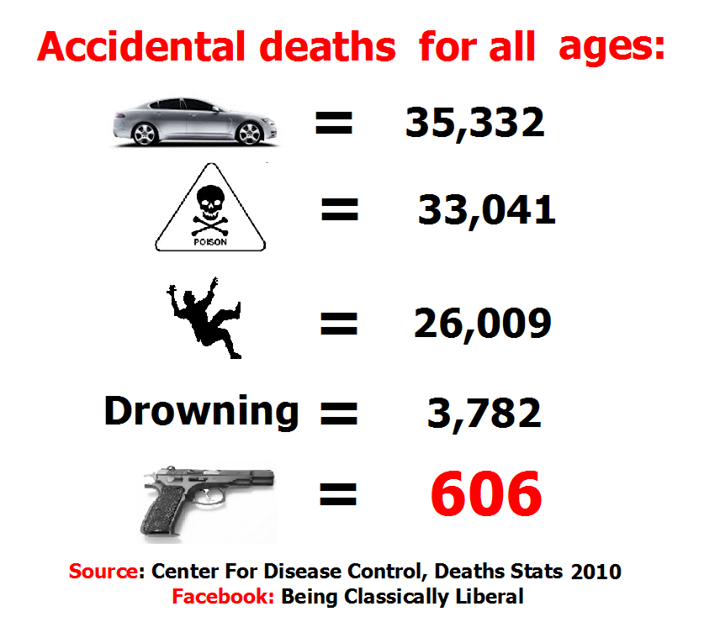

By contrast, guns are responsible for a minute fraction of accidental childhood deaths. Here’s a nice graphic representation of the difference:

With those risks, all of us want to protect against children drowning accidentally, especially in home pools that are meant to be there for family fun. There are two ways in my town to comply with the code requirements intended to protect children from drowning. First, you can install a fence immediately around the pool. There are some attractive — and extremely expensive — ways to make that happen:

Alternatively, you can fence off your entire yard with a six-foot high fence. We chose the latter option, because most of our yard is already fenced off to keep out deer and coyotes. All that we had to do was to replace a gate that was too short. Otherwise, it was a pretty minimal effort to comply with code.

Oh, and we had to do one other thing. For the two doors that we have that lead out to the yard, we had to install pool alarms. These are alarms that produce an ear-splitting racket if the door is opened, or left open, without punching a button or two. You can go the expensive route, and have all your doors set to a central system, like an ADT burglar alarm, or you can buy an affordable little DYI package. With this, you put one sensor on the sliding door or window and one sensor on the frame. When the sensors part ways, the alarm goes off.

The alarm is piercing. I was having some problems installing one of them today and, when I was standing right next to it, it made my ears really hurt, as in now, seven hours later, my left ear is hurting and I’m reasonably certain I sustained a small amount of permanent hearing loss.

Having gone through that set-up process, if I actually had small children, I’d go away content that my children are never going to slip out of the house without me knowing. But no! That assumption would be dumb! Dumb! Dumb! Dumb!

Because what I discovered today is that these sliding door guards in no way compensate for watching your children every second of the day to keep them safe. Although I don’t have a very large house, I have a wandering house. It’s not compact, with one story above another, nor is it a single level house. Instead, it’s an unevenly stacked split-level house that staggers drunkenly down a hill. What I discovered when I was struggling to get the damn alarm thing set right is that, while it deafened me (truly) when I was standing right next to it, I couldn’t hear it when I was at the far end of the house.

If I was cooking in the kitchen and my toddler tried to open the door to the pool, I would have known what was going on because I would be on the same level as, and one room away from, the alarm. However, if I was doing the laundry, at the far end of the house . . . no way would I have known that the alarm went off.

Further, to the extent these things rely on batteries, if your batteries fail, you are s**t out of luck. And while I’m sure that some people meticulously replace batteries every three to four months, whether they need it or not, most don’t. That’s why smoke detectors have that incredibly irritating beep-beep-beep signal, which always goes off in the middle of the night, to tell people when the batteries have died. Without that beep-beep-beep, most people would set it and forget it.

So imagine, there I am, a nice young mother with toddler twins. I’ve just put in the new swimming pool and, without any trouble, installed those sliding door alarms. And then I feel safe. I’ve put locks on the cabinets, protectors on the electrical outlets, gates across the stairs and, now, a sliding door alarm between the pool and the house. I’ve protected my darlings against all the known knowns and some of the known unknowns.

What I haven’t factored into all this moral hazard behavior, however, is all the unknown unknowns that are inevitable toddlers and young children: The fences one never thought they could climb, the busy fingers that make mincemeat of electrical outlet covers, and the alerts one doesn’t hear.

There is only one way to protect small children — those little unguided missiles who are all impulse and no control — from harm, and that’s to watch them like a hawk. Everything else is an imperfect crutch at best. If I ever have grandchildren roaming this house, I’m going to watch them closely or truly lock them off, rather than rely on a $40 government-mandated pool alarm to keep them safe.

Today, my very strong feeling is that this code requirement, rather than making children more safe, makes them less safe, because it encourages parental sloth in reliance upon the dubious protection of a cheap piece of electronics. That’s the problem with so many of the promises the government makes about our safety. Yes, some things really do matter, like a well-designed freeway or a reinforced housing frame in earthquake country. A lot of the promises the government makes, though, are illusory. They tempt us either into risky behavior or into unwarranted carelessness, thereby increasing the dangers we face.

At a fundamental level, when things are within our control, it’s our responsibility to keep our family safe, not the government’s. I can’t design my own car, so I appreciate having the marketplace offer safety features, but I can make decisions aimed at protecting my child in his own home, whether that means keeping any guns I might own locked up in a safe far from children or keeping an eagle-eye on my children in a home with a swimming pool.