Another splendid evening commemorating the Battle of Midway

For most Americans of a historic or patriotic bent, yesterday — June 6 — was a day to honor the incredible bravery of the American troops who stormed Normandy’s shores on June 6, 1944. Too many people have forgotten that, before D-Day, the Allies had no boots on the ground in the fight against the Germans. It was the incredible organizational abilities of the American military, combined with the staggering bravery of American men, that marked the beginning of the end of Nazi dominance in Western Europe.

For most Americans of a historic or patriotic bent, yesterday — June 6 — was a day to honor the incredible bravery of the American troops who stormed Normandy’s shores on June 6, 1944. Too many people have forgotten that, before D-Day, the Allies had no boots on the ground in the fight against the Germans. It was the incredible organizational abilities of the American military, combined with the staggering bravery of American men, that marked the beginning of the end of Nazi dominance in Western Europe.

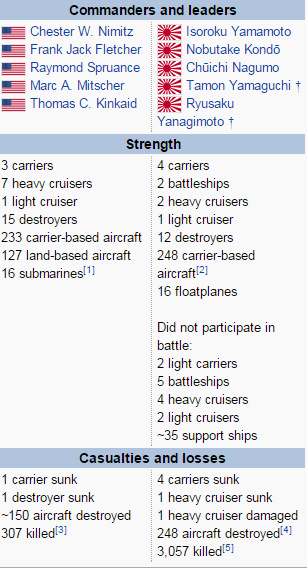

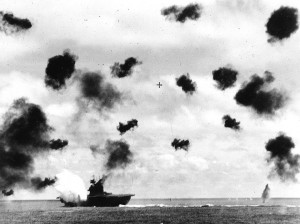

Almost two years to the day before D-Day, however, the American Navy won a staggering victory at seas — perhaps the greatest naval victory in American history — that marked the beginning of the end of Japan’s control over the Pacific. The Pacific war raged on for three more bloody, painful, and deadly years, but it was the Battle of Midway, which raged from June 4 to June 7, 1942, that dealt the Japanese a blow from which they never recovered. The numbers, which I’ve taken from Wikipedia, tell something of the story of the enormous odds against the Americans as they went into battle, something that makes their victory that much more inspiring:

As you can see, the Americans were grossly outnumbered, not to mention that USS Yorktown had been pieced together over the course of three frantic days in Pearl Harbor after the terrible damage she suffered at the Battle of the Coral Sea, yet Americans triumphed. A significant part of America’s victory was the extraordinary courage that members of the Navy and Marines — many of whom were quite new to the military — showed during the battle. The program I received at last night’s commemorative dinner, included a lovely contemporary quotation from Ensign William R. Evans, USN: a pilot of Torpedo Squadron 8, KIA at Midway, written on June 4, 1942. I’d like to quote it here:

Many of my friends are now dead. To a man, each died with a nonchalance that each would have denied as courage. They simply called it lack of fear. If anything great or good is born of this war, it should not be valued in the colonies we may win nor in the pages historians will attempt to write, but rather in the youth of our country, who never trained for war; rather almost never believed in war, but who have, from some hidden source, brought forth a gallantry which is homespun, it is so real.

When you hear others saying harsh things about American youth, do all in your power to help others keep faith with those few who gave so much. Tell them that out here, between a spaceless sea and sky, American youth has found itself and given itself so that, at home, the spark may catch. There is much I cannot say, which should be said before it is too late. It is my fear that national inertia will cancel the gains won at such a price. My luck can’t last much longer, but the flame goes on and on.

There was another kind of bravery on display at the Battle of Midway, and it was one that last night’s speaker, Admiral Scott “Notso” Swift, Commander of the Pacific Fleet, touched upon in his very thoughtful and thought-provoking speech to commemorate the 73rd anniversary of the Battle of Midway: The bravery of the admirals called upon to make the decisions in advance of the Battle, something they did without massive oversight, not to mention second-guessing, from people at desks thousands of miles away. (I did not take notes last night so I can only summarize what I understand him to say. Anything that sounds wrong is my fault, not his.)

Admiral Swift reminded the audience that the Americans had not cracked the Japanese code, although they did believe that they had a general idea of what the Japanese were communicating to each other. It was certain that the Japanese were planning a major, and imminent attack to cement their control over the Pacific, but nobody knew precisely when or, more importantly, where they were going to attack. The probable targets were eventually narrowed to two: Either the West Coast (Washington or California) or the small, but centrally located Midway Island. Admiral Nimitz was convinced that the battle would take place at Midway, but the desk jockeys in Washington were convinced the mainland coast would be the target.

Nimitz’s team used a false message about a water problem at Midway, which the Japanese promptly relayed, to prove pretty conclusively that a specific numerical sequence in the Japanese code did indeed refer to Midway. Having somewhat allayed the fears in D.C., Nimitz gave the order to prepare for battle. And so it was that the American Navy’s small and tattered fleet steamed out into the Pacific, looking everywhere in those vast, empty waters for the much larger Imperial Fleet.

I will embarrass myself by exposing my ignorance if I describe how American fliers, at enormous risk to themselves, found the Japanese fleet, or how bravely the men in planes and on board ships fought to bring about that almost miraculous victory. What I can relay, though, is something that Admiral Swift said, which really struck me. Admiral Nimitz, although he tracked the battle minute by minute, did not interfere with command decisions at the scene of the battle. He trusted the team he had assembled — and who were on the water, dealing with matters in real-time — to make the right decisions. His trust was rewarded, because his admirals, not to mention the men in their command, acted with courage, flexibility, and innovation to destroy the Japanese fleet. It took a lot of time and human capital before this blow was fully effective, but Midway was the turning point. From that point onward, the question wasn’t whether the Japanese would lose, it was when they would lose.

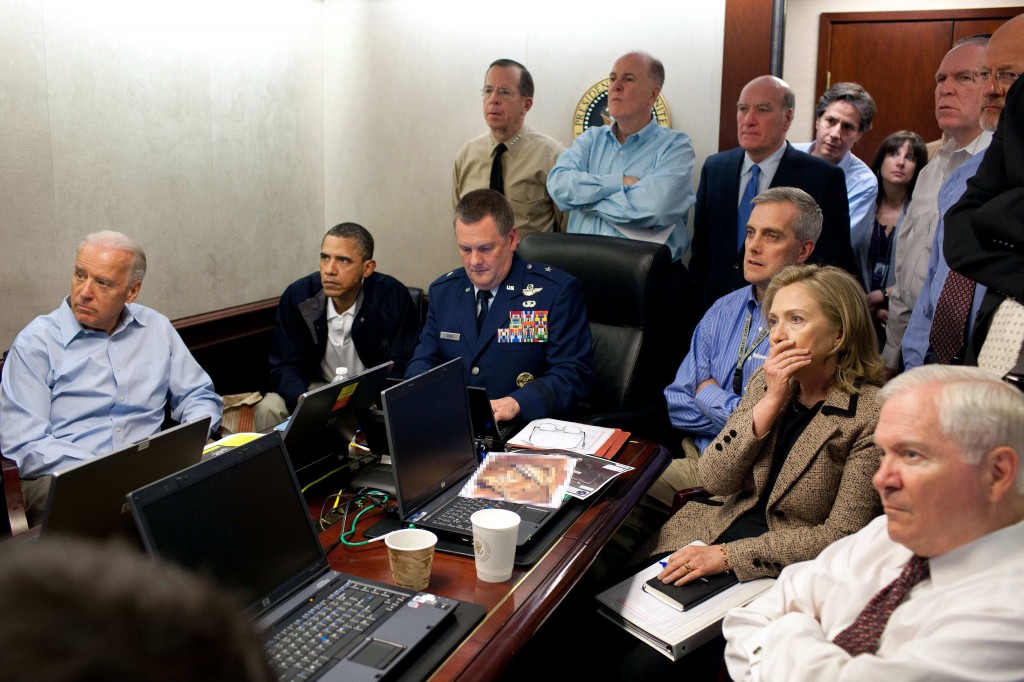

After having made this point about Nimitz’s willingness to trust his team, from the admirals on down, Admiral Swift said that our modern military today has a zero-tolerance attitude when it comes to mistakes. This attitude, while virtuous in its way (nobody wants the risk of a sloppily run, careless military), leads to micromanagement. Indeed, as a friend commented to me later, today’s communication advances mean that the people at the desks, from high-ranking military commanders to way too many lawyers, can oversee a battle in real-time, and provide running critique and commentary. Kind of like this:

My take on this is that, not only do too many cooks spoil the broth, there’s a problem when these cooks are focused on concerns other than winning a specific battle. Moreover, it can mean that important decisions get delayed while a message is being relayed down the line. For example, the same friend told me that D-Day might have turned out quite differently if Hitler hadn’t put himself in command. Although the commander of a Panzer division some 25 miles away from Normandy’s beaches could easily have moved in and destroyed the Americans, the Germans in Berlin who received the message about the D-Day landing were afraid to wake Hitler up. For that reason, there was a 12 hour delay before the Panzer commander was told to head for the beaches. By this time, though, the Americans were reinforced with men, vehicles, and weapons, and the German commander realized that he had lost his window of opportunity, and elected to regroup further inland.

Back to Admiral Swift’s speech, the Admiral said that, with excessive caution, micromanagement, and overly strong command-and-control (my words, not his), we run the risk of stifling the initiative, instinct, and moral courage that made possible victories such as Midway, victories that relied on experience, instinct, and a deep and abiding trust in ones team, starting with the admirals and captains, and running all the way down to the enlisted sailors. (Again, those are my words, not Admiral Swift’s, but I think that’s what he said.)

If I understand correctly what Admiral Swift was saying, this was a very important statement coming from the Commander of the Pacific Fleet, because it appears that he’ll use his position to give the people in his command more autonomy. Again, if I got this right, I highly approve of the idea. (If I got this wrong, someone correct me, please!!!)

I’ve focused on Admiral Swift’s talk, because I thought it was so interesting, but that wasn’t the only interesting part of the evening, of course. I’ve gone to enough Midway Commemorations to know a lot of people there and it’s a great pleasure every year to see them again, exchange hugs, and catch up a little. And as always, I delighted in the gorgeous setting at the Marines Memorial Club, enjoyed the delicious roast beef, and took a great deal of pleasure in seeing everyone dressed up in evening clothes and formal uniforms (complete with rows of ribbons, golden stripes marking years of service, and the insignia of their rank).

The one sad part of the evening was that only one Midway veteran was able to attend the dinner last night. I believe that the first time I went, perhaps six or seven years ago, there were fourteen. The one man who did attend was Navy Lieutenant Junior Grade Oral L. Moore, otherwise known as “Slim.” At the Battle of Midway, Slim was an Aviation Radioman, 3/c, flying in a Bombing Squadron 8 SBD dive bomber off of the hornet.

Although Slim’s plane wasn’t involved in the attack on the Japanese carriers at Midway, during a Search on June 6th, the plane’s pilot, Ensign W.D. Carter, spotted the Japanese cruisers Mikuma and Mogami. Because the Mogami had been damaged in a collision with the Mikuma, resulting in a shortened bow, Carter thought he was seeing a two different types of ships — one a standard heavy cruiser (the Mogami) and the other alarger battle cruiser (the Mikuma). Carter’s instructions to Slim led to a moment of historic confusion that was only cleared up sometime later. Here is what the book with veteran autobiographies has to say:

Believing he was seeing a standard heavy cruiser (MOGAMI) along with a larger battle cruiser (MIKUMA) with no bow damage), Carter told Moore over the dive bomber’s intercom to send “SIGHTED ONE CA, ONE CB” to the American task force. Moore had never heard of a “CB” (battle cruiser), and thought the pilot had said “ONE CA, ONE CV” (one cruiser, one carrier), which is what he sent via Morse code. It was correctly copied that way by radiomen aboard the USS Enterprise, where Admiral Spruance was astounded that another Japanese carrier was in the area. He ordered scouts in the air to find and verify the report. (Most written histories of the battle state that Moore’s message was garbled in transmission, resulting in the “CV” mistake, but that was not the case.)

A short while later VB-8 pilot Roy Gee [who also attended Midway commemorations] overflew Enterprise and dropped a handwritten message reporting “two cruisers” but at a position slightly different than the one reported by Carter and Moore. This led Spruance to believe he was dealing with two groups of enemy ships, and he ordered a full strike from the Hornet. The confusion wasn’t cleared up for another hour when Carter landed and corrected his original sighting report.

Slim was also in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, in October 1942, where he sustained injuries to his feed and leg. When he finally made it to sick bay on the Enterprise, he discovered himself next to one of his high school classmates!

Slim is quite frail now, and needed help getting around at the event. I’m not exaggerating when I say that the sailor who escorted him was bursting with pride to be able to take care of such a valiant man — valiant in 1942 and valiant in 2015.

Of course, there was no shortage of valiant men last night. Seated next to Slim at the dinner was a man from the Philippine Army who had survived the Bataan Death March. And presiding as President of the Mess was Rear Admiral Thomas F. Brown (Ret.), one of the Navy’s most distinguished pilots during Vietnam. Here are Admiral Brown’s statistics and awards from his time in the air over Vietnam. I can also tell you that he is an incredibly nice man — and must have been one hell of a math teacher, which is what he did after retiring from the Navy.

Overall, my evening at the 73rd Battle of Midway Commemoration dinner was as I expected it to be: interesting, fun, and very moving. I am always honored that the Navy opens its doors to people without a Navy background when it comes to this event.