Tom Hanks shows stunning ignorance when he claims Americans were engaged in racial genocide against the Japanese during WWII

“Back in World War II, we viewed the Japanese as ‘yellow, slant-eyed dogs’ that believed in different gods,” he told the magazine. “They were out to kill us because our way of living was different. We, in turn, wanted to annihilate them because they were different. Does that sound familiar, by any chance, to what’s going on today?” — Tom Hanks.

“‘The Pacific’ is coming out now, where it represents a war that was of racism and terror. And where it seemed as though the only way to complete one of these battles on one of these small specks of rock in the middle of nowhere was to – I’m sorry – kill them all. And, um, does that sound familiar to what we might be going through today? So it’s– is there anything new under the sun? It seems as if history keeps repeating itself.” — Tom Hanks.

We’ve long since grown accustomed to the fact that Hollywood’s actors periodically feel compelled to comment upon the world political scene, despite their manifest and abysmal ignorance. One could say that Tom Hanks is simply following an honored tradition when he makes appalling ignorant remarks about Japanese-American history in 1930s and 1940s. Or perhaps he’s more cynical, and he’s simply trying to drum up publicity (a la “there’s no such thing as bad publicity”).

I shouldn’t take Hanks’ remarks personally, but I do. You see, my mother was interned in a Japanese concentration camp in Indonesia from the time she was 17 until she was 21. I grew up with her stories, and I can tell you that the Japanese were indeed “different” — and that America, England, the British Commonwealth, and Holland were engaged in war with Japan, not because they were racist Western nations anxious to destroy “yellow, slant-eyed dogs,” but because they were faced with an unusually brutal and rapacious enemy. It was kill or be killed.

I am indebted to Victor Davis Hanson for his brief rundown of the historical ignorance that characterizes Hank’s (and other liberals’) beliefs about America’s relationship with Japan before Pearl Harbor:

In earlier times, we had good relations with Japan (an ally during World War I, that played an important naval role in defeating imperial Germany at sea) and had stayed neutral in its disputes with Russia (Teddy Roosevelt won a 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for his intermediary role). The crisis that led to Pearl Harbor was not innately with the Japanese people per se (tens of thousands of whom had emigrated to the United States on word of mouth reports of opportunity for Japanese immigrants), but with Japanese militarism and its creed of Bushido that had hijacked, violently so in many cases, the government and put an entire society on a fascistic footing. We no more wished to annihilate Japanese because of racial hatred than we wished to ally with their Chinese enemies because of racial affinity. In terms of geo-strategy, race was not the real catalyst for war other than its role among Japanese militarists in energizing expansive Japanese militarism.

In other words, while there’s no doubt that individual Americans may have expressed racial opinions about Japanese (something commonly done by all races about all other races in that pre-politically correct time), America did not have an inherently racist enmity towards the Japanese nation. Japan was simply a nation among nations: one with which America traded, made and broke convenient alliances, and observed from afar with a certain naive wonderment.

Japan, however, was not a nation like any other nations. As Hanson points out, the Bushido creed that Japan slavishly followed at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries had created a nation characterized by exceptional arrogance, and a disdain for “others” so profound that those “others” were reduced to the status of vermin who not only needed to be destroyed, but deserved to be destroyed. Nothing more clearly exemplifies this Bushido creed in action than the Rape of Nanking, a six week long bloodbath that occurred in 1937, when the Japanese invaded the Chinese city of Nanking. Steel yourself for the following description of Japanese atrocities (hyperlinks and footnotes omitted):

Rape

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East estimated that 20,000 women were raped, including infants and the elderly. A large portion of these rapes were systematized in a process where soldiers would search door-to-door for young girls, with many women taken captive and gang raped. The women were often killed immediately after the rape, often through explicit mutilation or by stabbing a bayonet, long stick of bamboo, or other objects into the vagina.

On 19 December 1937, Reverend James M. McCallum wrote in his diary :

I know not where to end. Never I have heard or read such brutality. Rape! Rape! Rape! We estimate at least 1,000 cases a night, and many by day. In case of resistance or anything that seems like disapproval, there is a bayonet stab or a bullet … People are hysterical … Women are being carried off every morning, afternoon and evening. The whole Japanese army seems to be free to go and come as it pleases, and to do whatever it pleases.

On March 7, 1938, Robert O. Wilson, a surgeon at the American-administered University Hospital in the Safety Zone, wrote in a letter to his family, “a conservative estimate of people slaughtered in cold blood is somewhere about 100,000, including of course thousands of soldiers that had thrown down their arms”.

Here are two excerpts from his letters of 15 and 18 December 1937 to his family :

The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Two bayoneted corpses are the only survivors of seven street cleaners who were sitting in their headquarters when Japanese soldiers came in without warning or reason and killed five of their number and wounded the two that found their way to the hospital.

Let me recount some instances occurring in the last two days. Last night the house of one of the Chinese staff members of the university was broken into and two of the women, his relatives, were raped. Two girls, about 16, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. In the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people the Japs came in ten times last night, over the wall, stole food, clothing, and raped until they were satisfied. They bayoneted one little boy of eight who have [sic] five bayonet wounds including one that penetrated his stomach, a portion of omentum was outside the abdomen. I think he will live.

In his diary kept during the aggression to the city and its occupation by the Imperial Japanese Army, the leader of the Safety Zone, John Rabe, wrote many comments about Japanese atrocities. For the 17th December:

Two Japanese soldiers have climbed over the garden wall and are about to break into our house. When I appear they give the excuse that they saw two Chinese soldiers climb over the wall. When I show them my party badge, they return the same way. In one of the houses in the narrow street behind my garden wall, a woman was raped, and then wounded in the neck with a bayonet. I managed to get an ambulance so we can take her to Kulou Hospital … Last night up to 1,000 women and girls are said to have been raped, about 100 girls at Ginling College Girls alone. You hear nothing but rape. If husbands or brothers intervene, they’re shot. What you hear and see on all sides is the brutality and bestiality of the Japanese soldiers.

There are also accounts of Japanese troops forcing families to commit acts of incest. Sons were forced to rape their mothers, fathers were forced to rape daughters. One pregnant woman who was gang-raped by Japanese soldiers gave birth only a few hours later; although the baby appeared to be physically unharmed (Robert B. Edgerton, Warriors of the Rising Sun). Monks who had declared a life of celibacy were also forced to rape women.

Murder of civilians

On 13 December 1937, John Rabe wrote in his diary :

It is not until we tour the city that we learn the extent of destruction. We come across corpses every 100 to 200 yards. The bodies of civilians that I examined had bullet holes in their backs. These people had presumably been fleeing and were shot from behind. The Japanese march through the city in groups of ten to twenty soldiers and loot the shops (…) I watched with my own eyes as they looted the café of our German baker Herr Kiessling. Hempel’s hotel was broken into as well, as almost every shop on Chung Shang and Taiping Road.

On 10 February 1938, Legation Secretary of the German Embassy, Rosen, wrote to his Foreign Ministry about a film made in December by Reverend John Magee to recommend its purchase. Here is an excerpt from his letter and a description of some of its shots, kept in the Political Archives of the Foreign Ministry in Berlin.

During the Japanese reign of terror in Nanking – which, by the way, continues to this day to a considerable degree – the Reverend John Magee, a member of the American Episcopal Church Mission who has been here for almost a quarter of a centuty, took motion pictures that eloquently bear witness to the atrocities committed by the Japanese …. One will have to wait and see whether the highest officers in the Japanese army succeed, as they have indicated, in stopping the activities of their troops, which continue even today.

On December 13, about 30 soldiers came to a Chinese house at #5 Hsing Lu Koo in the southeastern part of Nanking, and demanded entrance. The door was open by the landlord, a Mohammedan named Ha. They killed him immediately with a revolver and also Mrs. Ha, who knelt before them after Ha’s death, begging them not to kill anyone else. Mrs. Ha asked them why they killed her husband and they shot her dead. Mrs. Hsia was dragged out from under a table in the guest hall where she had tried to hide with her 1 year old baby. After being stripped and raped by one or more men, she was bayoneted in the chest, and then had a bottle thrust into her vagina. The baby was killed with a bayonet. Some soldiers then went to the next room, where Mrs. Hsia’s parents, aged 76 and 74, and her two daughters aged 16 and 14. They were about to rape the girls when the grandmother tried to protect them. The soldiers killed her with a revolver. The grandfather grasped the body of his wife and was killed. The two girls were then stripped, the elder being raped by 2–3 men, and the younger by 3. The older girl was stabbed afterwards and a cane was rammed in her vagina. The younger girl was bayoneted also but was spared the horrible treatment that had been meted out to her sister and mother. The soldiers then bayoneted another sister of between 7–8, who was also in the room. The last murders in the house were of Ha’s two children, aged 4 and 2 respectively. The older was bayoneted and the younger split down through the head with a sword.

Pregnant women were a target of murder, as they would often be bayoneted in the stomach, sometimes after rape. Tang Junshan, survivor and witness to one of the Japanese army’s systematic mass killings, testified:

The seventh and last person in the first row was a pregnant woman. The soldier thought he might as well rape her before killing her, so he pulled her out of the group to a spot about ten meters away. As he was trying to rape her, the woman resisted fiercely … The soldier abruptly stabbed her in the belly with a bayonet. She gave a final scream as her intestines spilled out. Then the soldier stabbed the fetus, with its umbilical cord clearly visible, and tossed it aside.

Thousands were led away and mass-executed in an excavation known as the “Ten-Thousand-Corpse Ditch”, a trench measuring about 300m long and 5m wide. Since records were not kept, estimates regarding the number of victims buried in the ditch range from 4,000 to 20,000. However, most scholars and historians consider the number to be more than 12,000 victims.

The Japanese officers turned the act of murder into sport. They would set out to kill a certain number of Chinese before the other. Young men would also be used for bayonet training. Their limbs would be restrained or they would be tied to a post while the Japanese soldiers took turns plunging their bayonets into the victims’ bodies.[citation needed]

Although revisionists are trying to rewrite this bit of history, I incline to the traditional history, both because contemporary eyewitness accounts and photographs tend to be a giveaway, and because the Japanese exhibited similar behavior (although with less rape) half a decade later during World War II.

The Bataan death march serves as a perfect example of the Japanese capacity for almost unparalleled brutality — brutality made worse in this instance by the fact that, under the Bushido doctrine, surrendering soldiers were objects of special contempt (again, footnotes and hyperlinks omitted):

At dawn on 9 April, and against the orders of Generals Douglas MacArthur and Jonathan Wainwright[citation needed], Major General Edward P. King, Jr., commanding Luzon Force, Bataan, Philippine Islands, surrendered more than 75,000 (67,000 Filipinos, 1,000 Chinese Filipinos, and 11,796 Americans) starving and disease-ridden men. He inquired of Colonel Motoo Nakayama, the Japanese colonel to whom he tendered his pistol in lieu of his lost sword, whether the Americans and Filipinos would be well treated. The Japanese aide-de-camp replied: “We are not barbarians.” The majority of the prisoners of war were immediately robbed of their keepsakes and belongings and subsequently forced to endure a 61-mile (98 km) march in deep dust, over vehicle-broken macadam roads, and crammed into rail cars to captivity at Camp O’Donnell. Thousands died en route from disease, starvation, dehydration, heat prostration, untreated wounds, and wanton execution.

Those few who were lucky enough to travel to San Fernando on trucks still had to endure more than 25 miles of marching. Prisoners were beaten randomly, and were often denied food and water. Those who fell behind were usually executed or left to die. Witnesses say those who broke rank for a drink of water were executed, some even decapitated. Subsequently, the sides of the roads became littered with dead bodies and those begging for help.

On the Bataan Death March, approximately 54,000 of the 75,000 prisoners reached their destination. The death toll of the march is difficult to assess as thousands of captives were able to escape from their guards. All told, approximately 5,000–10,000 Filipino and 600–650 American prisoners of war died before they could reach Camp O’Donnell.

I don’t need to look to history books and websites, though, to understand that the Japanese were indeed different from the Americans. I just have to turn inwards and resurrect the stories my mom told me as I was growing up.

In 1941, my mother was a 17 year old Dutch girl living in Java. Life was good than. Although the war was raging in Europe, and Holland had long been under Nazi occupation, the colonies were still outside the theater of war. The colonial Dutch therefore were able to enjoy the traditional perks of the Empire, with lovely homes, tended by cheap Indonesian labor. All that changed with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Most Americans think of Pearl Harbor as a uniquely American event, not realizing that it was simply the opening salvo the Japanese fired in their generalized war to gain total ascendancy in the Pacific. While Pearl Harbor devastated the American navy, the Japanese did not conquer American soil. Residents in the Philippines (American territory), Indonesia (Dutch territory), Malaya (British territory), and Singapore (also British) were not so lucky. Each of those islands fell completely to the Japanese, and the civilians on those islands found themselves prisoners of war.

In the beginning, things didn’t look so bad. The Japanese immediately set about concentrating the civilian population by moving people into group housing, but that was tolerable. The next step, however, was to remove all the men, and any boys who weren’t actually small children. (Wait, I misspoke. The next step was the slaughter of household pets — dogs and cats — which was accomplished by picking them up by their hind legs and smashing their heads against walls and trees.)

Once separated, the men and women remained completely segregated for the remainder of the war. The men were subjected to brutal slave labor, and had an attrition rate much higher than the women did. Also, with the typical Bushido disrespect for men who didn’t have the decency to kill themselves, rather than to surrender, the men were tortured at a rather consistent rate.

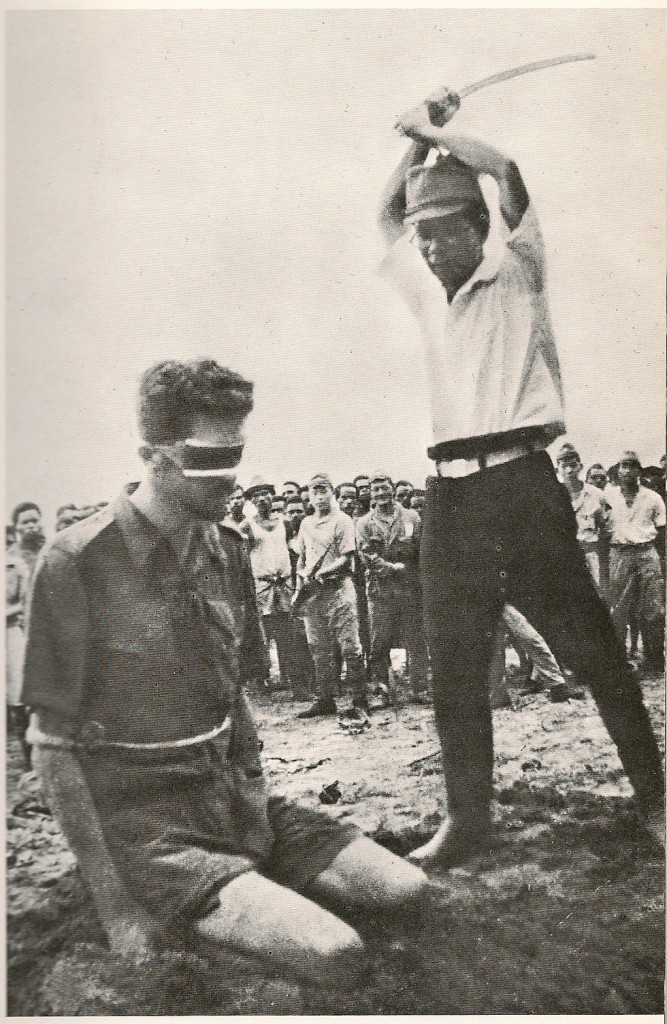

One of my mother’s friends discovered, at war’s end, that her husband had been decapitated. This is what it looked like when the Japanese decapitated a prisoner (the prisoner in this case being an Australian airman):

The women were not decapitated, but they were subjected to terrible tortures. After the men were taken away, the women and children were loaded in trucks and taken to various camps. The truck rides were torturous. The women and children were packed into the trucks, with no food, no water, no toilet, facilities, and no shade, and traveled for hours in the steamy equatorial heat.

Once in camp, the women were given small shelves to sleep on (about 24 inches across), row after row, like sardines. They were periodically subjected to group punishments. The one that lives in my mother’s memory more than sixty years after the fact was the requirement that they stand in the camp compound, in the sun, for 24 hours. No food, no water, no shade, no sitting down, no restroom breaks (and many of the women were liquid with dysentery and other intestinal diseases and parasitical problems). For 24 hours, they’d just stand there, in the humid, 90+ degree temperature, under the blazing tropical sun. The older women, the children and the sick died where they stood.

There were other indignities. One of the camp commandants believed himself to have “moon madness.” Whenever there was a full moon, he gave himself license to seek out the prisoners and torture those who took his fancy. He liked to use knives. He was the only Japanese camp commandant in Java who was executed after the war for war crimes.

Of course, the main problem with camp was the deprivation and disease. Rations that started out slender were practically nonexistent by war’s end. Eventually, the women in the camp were competing with the pigs for food. If the women couldn’t supplement their rations with pig slop, all they got was a thin fish broth with a single bite sized piece of meat and some rice floating in it. The women were also given the equivalent of a spoonful of sugar per week. My mother always tried to ration hers but couldn’t do it. Instead, she’d gobble it instantly, and live with the guilt of her lack of self-control.

By war’s end, my mother, who was then 5’2″, weighed 65 pounds. What frightened her at the beginning of August 1945 wasn’t the hunger, but the fact that she no longer felt hungry. She knew that when a women stopped wanting to eat, she had started to die. Had the atomic bomb not dropped when it did, my mother would have starved to death.

Starvation wasn’t the only problem. Due to malnourishment and lack of proper protection, my mother had beriberi, two different types of malaria (so as one fever ebbed, the other flowed), tuberculosis, and dysentery. At the beginning of the internment, the Japanese were providing some primitive medical care for some of these ailments. By war’s end, of course, there was no medicine for any of these maladies. She survived because she was young and strong. Others didn’t.

So yes, the Japanese were different. They approached war — and especially civilian populations — with a brutality equaled only by the Germans. War is brutal, and individual soldiers can do terrible things, but the fact remains that American troops and the American government, even when they made mistakes (and the Japanese internment in American was one of those mistakes) never engaged in the kind of systematic torture and murder that characterized Bushido Japanese interactions with those they deemed their enemies. It is a tribute to America’s humane post-WWII influence and the Japanese willingness to abandon its past that the Bushido culture is dead and gone, and that the Japanese no longer feel compelled by culture to create enemies and then to engage in the systematic torture and murder of those enemies.

For Tom Hanks to try to create parallelism between the Japanese and Americans at any time between 1941 and 1945 is simply an obscene perversion of history that should be challenged at every level. It wouldn’t matter so much, of course, if Tom Hanks was just a garden-variety ignoramus. The problem is that he’s got a platform, a big platform, and he’s going to use it for all he’s worth to pervert the past in order to control the present and alter the future.