The problem with introducing freedom into industrial societies — or the tyranny of fossil fuels

Two things happened on November 26, two entirely unrelated things, that nevertheless ended up merging into a single thought in my mind: In the modern world, fossil fuels equal liberty. If you cannot assure the people the former, forget about trying to foist upon them the latter. Let me walk you through my thought processes.

The first thing that impinged onto my awareness was a conversation I had with a most delightful 85-year-old Jewish man who, except for WWII and the Israeli War of Independence, has always lived and worked in South Africa. During a wide-ranging conversation, I asked him what the situation was like today in post-apartheid South Africa. “Horrible,” he said, “just horrible.” According to him, the moment Nelson Mandela left office, the new ANC government began to be as racist as the old apartheid government, only with the benefits flowing to the blacks, this time, not the whites. It’s not Zimbabwe, yet, but he sees it coming.

What was most fascinating to me was this man’s claim that the black people are deeply unhappy with the status quo. Yes, ostensibly they have civil rights that were denied them under the old regime. The problem, though, is that the country is so horribly mismanaged under the current government that, while they have civil rights, they lack electricity, clean water, food and transportation. The blacks he speaks to therefore look back longingly on apartheid. While their lives then were demeaning and economically marginal, the old government was stable and efficient. Excepting those who lived in the most abysmal poverty, apartheid-era blacks could rely on what we in the modern era consider to be the basics for sustaining life: not just the bare minimum of food and water, but also electricity, reliable long-distance transportation, and plumbing — all of which are dependent upon a modern fossil fuel economy.

The second thing that happened on November 26 was that Danny Lemieux put up a post commenting on Bruce Bawer’s Thanksgiving article examining the possibly naive American notion that all people crave freedom. Danny had this to say:

I believe that I can understand the pull of serfdom for many people. Just think of all of the difficult life decisions that are taken away from the individual serf: as wards of the state, they don’t have to worry about where they will get their food (of course, they can forget about shopping at Whole Foods as well), whether they will meet their financial needs (albeit at a subsistence level), understanding politics, moral values, education, finding a job…etc. It is, in other words, regression to the mind of a child. They can simply exist for the moment of the day: no responsibilities but, also, no hope. Like vegetables, if you think about it.

I agree with Danny (and Bruce Bawer), but I I’d like to add to what both say, by dragging in fossil fuels.

What may have made the extraordinary American experiment in individual liberty possible was that it happened right at the start of the industrial era, before people’s expectations were raised by the industrial and post-industrial era. At the end of the 18th century, people’s material expectations were limited by the technology of the time (electricity was a lightening bolt; clean water was the creek behind your house; transportation could be found in the bones and muscles reaching from your hips down to your feet). Fortunately for America’s future, she was rich, not only in space, but in the natural resources that would become so necessary in the next two centuries, including fossil fuel and the drive to put that fossil fuel to work. Put another way, at the moment our nation was born, our material expectations were low, but the possibilities proved to be almost endless. The exquisite historic timing that brought together our new freedoms and the nascent industrial revolution made the American miracle possible.

Nowadays, the source of all physical comfort is fossil fuel. Except for those people who still live a virtually stone age existence (whether in Indian, Africa, Latin America or Asia), every single person in the world benefits from fossil fuels. They give us light, water treatment plants for clean water, food in the fields and in the marketplace, transportation, clothing, housing, every bit of our technology, everything. Nothing in our modern world would be possible without them. Fossil fuels drove Hitler’s maniacal push to the Soviet Union and ended the Japanese ability to fight a war. (If you’re interested in more on oil’s central role in WWII, check out The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power.) No wonder the global warmists, with their anti-Western mindset, are so determined to destroy fossil fuel.

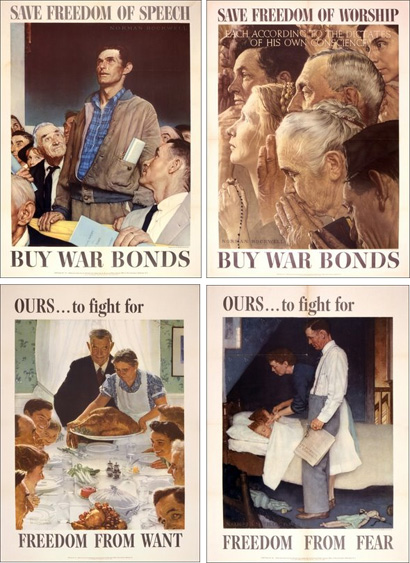

In a modern world, one that premised upon expectations of fossil fuel’s blessings (an abundance of food, clean water, ready transportation, technical, etc.), giving people freedom without meeting those expectations — which are, by now, the minimal expectations for creature comfort — is doomed to failure. It is no longer enough to couple free speech with a horse, a plow, and some seeds. Nor will people be excited about freedom of worship if they have only a small flame to light the night-time darkness. Today, America’s famous four freedoms will satisfy people only if they are coupled with the riches flowing from modern energy.

What all this means in practical terms is that, if you invade Iraq and destroy a tyrant, but simultaneously knock out the power supply, you will not have a happy population. Post-industrial people would rather have tyranny and electricity (and the food, water, transportation and other things flowing from that electricity), than freedom in a world limited to stone age energy sources. Proverbs 15:17 therefore got it wrong. As you recall, that proverb says “Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith.” Our modern experience with trying to bring people to the American model shows that most would say, “Better a stalled ox and a well-lighted barn where tyranny is, than starvation and the darkness of night where freedom lives.”