Leftist politics and the power of visual images

Leftists know that people respond strongly to visual images and use them to great effect. If Republicans want to win, they need to start doing the same.

A picture is worth a thousand words. — Newspaper/advertising adage.

Some years ago, in a post I wrote about the Second Amendment, I noted the fact that one of the advantages the gun-grabbing crowd has when pushing its message is that it has the intense visuals of dead bodies (something the Left used with special force in the wake of the terrible Sandy Hook massacre). This means that these same anti-gun people are completely resistant to any data that doesn’t create powerful images.

Some years ago, in a post I wrote about the Second Amendment, I noted the fact that one of the advantages the gun-grabbing crowd has when pushing its message is that it has the intense visuals of dead bodies (something the Left used with special force in the wake of the terrible Sandy Hook massacre). This means that these same anti-gun people are completely resistant to any data that doesn’t create powerful images.

When it comes to guns, the gun grabbers suffer from a very bizarre limitation: Their mental horizons allow them to see only those who died because of guns, not to recognize those who did not die thanks to guns. This myopia creates the giant intellectual chasm that separates those who oppose the Second Amendment from those who support it. The former see only the people who died in the past while the latter also see the ones who will live on into the future.

I then introduced Frédéric Bastiat’s magnificent Parable of the Broken Window, which the French economist wrote in 1850, to make the point that destruction doesn’t benefit the economy but instead has money flowing in a fairly meaningless loop. Thus, Bastiat noted how people consoled someone whose window had been broken by pointing out that the repair meant work for the glazier and the contractor and so on. These people, said Bastiat, saw positive economic energy without ever understanding that it was actually lost economic energy because the money could have been used to create, rather than repair. What appealed to me about Bastiat’s essay was the final paragraph (emphasis mine):

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, “Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.”

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

After quoting the Parable, I dragged the issue around to the war that the Left is constantly waging against the Second Amendment:

Just as is the case with the economic illiterate who cannot imagine that money might be spent on something more useful than fixing a broken window, a gun control advocate’s world view “is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.” He counts those who have died, but cannot even begin to imagine those whose lives were saved or never threatened.

Point such an advocate to a story about an off-duty deputy who was able to stop a mall shooter, and he will say only that, “The gun still allowed the shooter to kill one or two people, and there’s no way to tell if the shooter intended to kill more people, so the armed deputy is not relevant.”

To the gun-control proponent, a story without dead bodies is no story at all and it certainly has no statistical validity in the debate over the Second Amendment. To one who believes in the Second Amendment, however, stories about people using concealed-carry guns to stop mass shooters matter because we, unlike the gun grabber, are able to take account of those people who survived what would otherwise have been a mass shooting.

Dead bodies resonate in our imagination. The absence of dead bodies, even when reported at excellent sites such as Ammo.com, which tracks stories about defensive gun use, is an empty space in the imagination. This is especially true because the media, even before it became fanatically determined to destroy the Second Amendment, always operated on the principle that “if it bleeds, it leads.” If it doesn’t bleed, it will at most be a feel good story in the last 30 seconds of the news or a squiblet on the last page of Section C in the local newspaper.

With no blood and no bodies, those who support the Second Amendment find themselves limited to statistics. The statistics, frankly, are spectacular, with an Obama-era study showing that people across the U.S. routinely and successfully use guns to defend themselves between 500,000 to 3 million times per year. Statistics, however, are not visual. Instead, they’re dead numbers on a page, exciting only to wonks and people who work well with abstract ideas.

The abortion debate has also been intensely visual. Before modern science allowed us to peer into the womb, the visuals of abortion were about the women: Pregnant women dying in back alleys from coat-hanger abortions, pregnant women whose cruel families cast them out on the street in the dead of winter, pregnant women chained to wife-beating husbands even as 13 other children were clinging to their aprons, brilliant pregnant women forced to drop out of school to become brood mares, and so on. No wonder that Obama announced to the world that he didn’t want his daughters “punished with a baby.”

The rise of more pro-Life Americans coincides with the rise of windows into the womb. (And yes, I know correlation and causation are not the same thing, but I’m pretty sure I’ve seen articles pointing to studies that show that 3D ultrasounds make people less supportive of abortion.) Suddenly, it’s not just a bump in a woman’s belly until the moment it’s born; instead, we see inside — in 3D yet! We see the fingers and toes, we see it sucking it’s thumb, we see that it is a baby. It’s visual.

The pro-Life movement also went visual when it started showing graphic photographs of aborted babies. The pro-Abortion movement hates those images. While dead bodies work in their favor in the Second Amendment debate, they do not help in the pro-Abortion debate. No more hypothetical women are dying in back alleys; instead, lots of actual, quite obvious babies are dying in Planned Parenthood clinics.

Apropos the abortion debate, Scott Adams, without touching on the merits of the new abortion limitations passed in Alabama, simply said that the fact that it was primarily men who voted on the law is a very bad visual, never mind the fact that a woman proposed the law and that a woman governor signed the law. Because pro-Abortion people have framed the issue as “control over a woman’s body,” it looks bad when men make policy. The fact that nine men created a right to abortion out of whole cloth back in 1973 is irrelevant. In the here and now, the Left points to Alabama’s legislature and says of the men, “they’re gonna put y’all woman back to being barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen.”

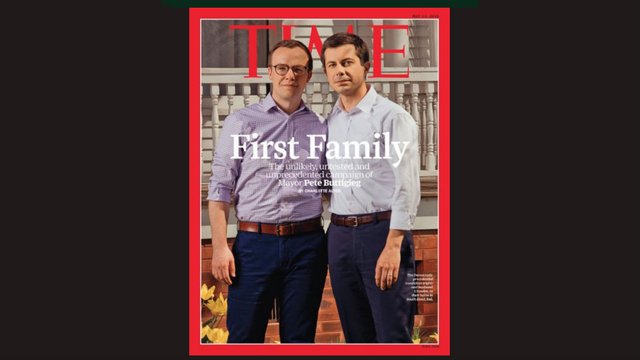

I was reminded of the power of visuals when I read an article in Los Angeles Review of Books’ blog, entitled Heterosexuality Without Women. The premise for the article is an image. This image:

The essay’s author — Greta LaFleur — urges us to take in every aspect of that image, not just because of the white house behind them (the “White House” metaphor . . . get it?), but also because it shows a sweet domesticity of husband and wife except without an actual female wife. After all, who needs real women to promote heterosexuality when you have this perfect gay heterosexual couple? If you’re saying “huh?”, you have to read the article. I’m quoting the pertinent parts (for my purposes) here:

There’s a lot to look at in this image. At first glance, one sees the anonymity of Norman Rockwell’s mid-century America: the house-unparticular porch, the timelessness of the couple form. Take another look and the pillars supporting the unseen roof of the porch start to resemble the Ionic columns of the White House, the background becoming a gesture or a promise of possibility. You begin to see the image in the aggregate, and the couple, girded by a backdrop literally overwhelmed by the household, becomes the timelessness of the entire image. This photo also tells a profound story about whiteness, above and beyond the fact that almost everything in this photo is, itself, white. It’s such an all-consuming aesthetic, here, that it practically resists interpretation; like the generically familiar (to me, a white person) porch, the cover photo claims that there’s nothing to see, because we already know what it is. We have seen this image, we know this couple, “we” should be comfortable. My “we” is particular to me, but then again, I am more or less exactly who this photo is aimed at. As a queer person, I also notice the quasi-uniform-like aesthetic of Pete and Chasten — I wondered, for a second, if they were actually wearing the same pair of pants — marveling for a moment at the sartorial doppel-banging that at first seems to claim center stage in this photo, before realizing that, instead, there’s actually no sex at center stage, here. And that is part of the point.

LaFleur goes on to point to new age scholarship that says, if I understand all the jargon correctly, that “whiteness” is now some sort of conceptual thing without the necessity of anybody being white. And why not? If gender, which is hardwired in every mammal at a DNA level, is now a mere concept, why can’t whiteness be a concept too? (Of course, blackness cannot be a concept, because that’s claiming unearned victim status not to mention racial and cultural appropriation. It’s always a one way street with these things. Likewise, homosexuality, which is a behavior, not a DNA thing, is also hard wired. Again, go figure. The new rules don’t have to make sense.)

Using this “conceptual whiteness” thing as a springboard, LaFleur makes the obvious leap: If “whiteness” is merely conceptual, than so is heterosexuality. Get enough heterosexual images piled into a single photograph and who cares if there’s not an actual heterosexual within a hundred miles?

This is a record with deep grooves. If you need more to convince you of this than the huge, literally white “FAMILY” emblazoned across Chasten and Pete’s well-muscled, Ralph Lauren-clad chests, then perhaps google “queer” and “focus on the family” and read a number of important and importantly-aging articles on the strategic deployment of homophobia (not to mention a host of other forms of animus) under the auspices of protecting “family values”; for conservatives of all stripes, the family was the antidote to the homosexual. The flip side of that effect is, of course, the distinct but twinned use of “family” in queer communities, first to name ties to other queer people that exceed socially-approbated forms of kinship, and, second, the reproduction of the hothouse family by queer people used to shore up the recognizability and respectability of queer love, connection, parenting, and marriage. (We really don’t need anything more than Cathy Cohen’s 1997 “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens” to teach us about how this works.) Queer theorists and queer communities have coined terms like homonormativity to describe this effect, but this recent Time cover left me wondering: is this homonormativity? Or just heterosexuality? If straight people can be queer — as so many of them seem so impatient to explain to me — can’t gay people also be straight?

To be clear, I have no intention of relegating “family” to the realm of the heterosexual or the straight, for a number of reasons that reflect things like the fact that most queer people have strong ties to family, given and/or chosen. What I am saying is that the unmistakable heraldry of “FIRST FAMILY,” alongside the rest of the photograph — the tulips; the Chinos; the notably charming but insistently generic porch; the awkwardly minimal touching that invokes the most uncomfortable, unfamiliar, culturally-heterosexual embrace any of us have ever received — offers a vision of heterosexuality without straight people.

Frankly, I think most of the above is gobbledy-gook, but I actually respect the way LaFleur is trying to reframe people’s visuals. Democrats know that this is how you win arguments.

While conservatives spout statistics about the number of illegal immigrants crossing into America, the burden they place on our welfare system, and the American workers they displace, Leftists create images: “Dead children.” “Children in cages.”

Statistics don’t touch the power of those images. After all, it was a photo of a single dead child in the sand that caused Europe to open its doors to every Muslim across in the Middle East and North Africa, something that threatens to destroy the last tendrils of Enlightenment, Christian Europe. If that poor little boy hadn’t died, the European open borders crowd would have had to kill someone to create that type of powerful persuader.

The same image problem exists when it comes to vaccinations. Once upon a time, Americans had powerful images associated with epidemic diseases. Small pox ravaged America in the 17th and 18th centuries, so much so that people embraced variolation (a dangerous vaccination process with a live virus) because, while it carried risks, the risks were infinitesimal compared to the devastation of epidemic small pox. One of the geniuses of George Washington was to order the mass vaccination of his American troops — a tradition that continues to this day, as every human pin cushion who’s ever served in the American military will attest.

You don’t have to go back as far as Washington to find epidemic diseases. My uncle had the Spanish Influenza, which killed 50-100 million people worldwide. My mother had diphtheria, a childhood scourge for hundreds of years before vaccinations became available. My father had scarlet fever, which was, as one site explains: a very bad disease in a pre-antibiotic era:

Simply hearing the name of this disease, and knowing that it was present in the community, was enough to strike fear into the hearts of those living in Victorian-era United States and Europe. This disease, even when not deadly, caused large amounts of suffering to those infected. In the worst cases, all of a family’s children were killed in a matter of a week or two.

There’s no vaccination for this strep infection, but we nail it today with antibiotics. (And are rightly concerned that antibiotic abuse might give the infection an unbeatable edge in the near future.)

We also had a family friend who lived out his days walking on two canes, in great pain, because he was one of the last children to get polio before Salk developed his vaccine. Before that vaccine, polio swept through the U.S. several times, killing children and adults, and leaving many survivors with paralysis or even locked forever in iron lungs.

My point is that, within the lifetime of people I knew very well, infectious diseases were incredibly visible. People died from them. People were left permanently invalided by them. People were left crippled because of them. In that world, the risks inherent in any vaccination, while real, was easily disregarded compared to the much greater risk of epidemic, pandemic, or endemic infectious diseases.

Nowadays, of course, none of these diseases are visible. Ebola is probably the main exception, for it still has the power to frighten. We’ve very quickly become accustomed, though, to Ebola’s politely staying in little corners of Africa, with saintly aide workers putting their lives on the line to confine the deaths to hundreds, rather than millions. Even AIDS, a scary contagious disease in the 1980s, has been shoved away, thanks to antiviral treatments and condoms.

The invisibility of epidemic diseases is why fewer and fewer young parents are willing to expose their children to the risk of vaccinations. We don’t see the diseases, but we do read the random articles about that inevitable unlucky person — that 1 in 1,000 or 1 in 10,000 person — who died following a vaccination. That in-your-face story, that “there but for the grace of God” visual is way more scary than some hypothetical epidemic — or at least, it’s more scary right up until people teaming with infectious diseases pour unchecked across our border and are dispersed throughout the United States. That’s when, as they say, “shit gets real.”

I just got myself a measles booster because I’m at the perfect age to have had an ineffective booster when I was a child. A lot of others are doing the same thing because they can now envision a measles epidemic, something they could not before.

I could go on and on making the point that, because people are visual, the best persuasion creates images, whether in the form of actual pictures or in the form of vivid phrases (e.g., “children in cages”). If Republicans want to take back the culture generally, and take back Washington D.C. specifically, they would do well to keep the statistics in the background and push the punchy, catchy, visceral, memorable images and word pictures to the foreground. (Of course, as matters now stand, when innovative conservatives do try to make powerful visuals, social media tech overlords instantly shut them down. Indeed, in California, they prosecute people for powerful images.)