This year’s race for president is an eerie repeat of the early days of the 1920 election season

A corrupt politician, a communist, a “government by expert” guy, and a pro-American iconoclast are running for president. This is 1920 all over again.

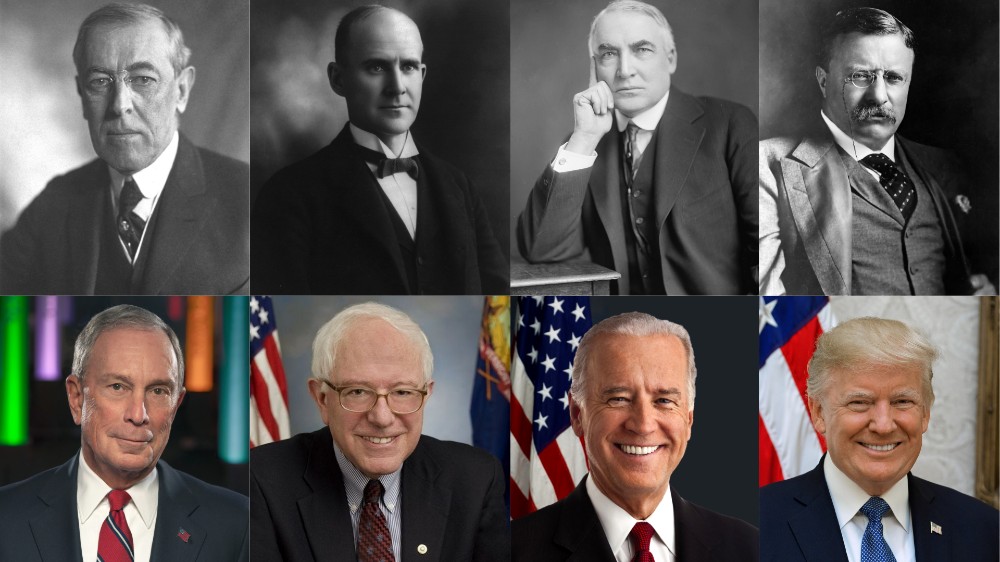

The presidential election in 1920 was a very interesting one. At the end of the day, the race boiled down to a contest between the Republican Warren G. Harding and the Democrat James M. Cox. However, in the lead-up to the election, a more interesting field was in play. Here were four of the candidates:

Woodrow Wilson, the current president, wanted to run again despite the fact that he had been felled by a stroke. For obvious reasons, the Democrat party didn’t want an ailing man who was, by then, quite unpopular.

Eugene V. Debs, a hardcore socialist, made his fourth run for president, something he did from inside a prison cell.

Warren G. Harding, a former U.S. Senator, was the quintessential “smoke-filled room” candidate.

Teddy Roosevelt, a colorful character who had been president from 1901 through 1909, also wanted to run again.

That’s the short version about those men. Here’s the longer version, along with a little bit about their modern political cognates in the presidential race.

Woodrow Wilson was America’s first progressive president. He represented the culmination of an upper-middle-class movement that believed in better living through expertise. Not just any expertise, though, but government expertise. An academic who was certain that he knew best, he believed that the Constitution was a limiting document that prevented him from micromanaging the American people for their own benefit.

Randolph J. May sums up nicely Wilson’s approach to government:

Wilson was convinced, in no small measure by his admiration for prominent late 19th century German social scientists, that “modern government” should be guided by administrative agency “experts” with specialized knowledge beyond the ken of ordinary Americans — and that these experts shouldn’t be unduly constrained by ordinary notions of democratic rule or constitutional constraints.

So, in his seminal 1887 article, “The Study of Administration,” published in the same year that the first modern regulatory commission, the Interstate Commerce Commission, was created, Wilson explained that he wanted to counter “the error of trying to do too much by vote.” Hence, he admonished that “self-government does not consist in having a hand in everything,” while pleading for “administrative elasticity and discretion” free from checks and balances.

[snip]

Wilson well understood that his notion of Progressive governance by “fourth branch” administrative experts was constitutionally problematic. In 1891, he wrote that “the functions of government are in a very real sense independent of legislation, and even constitutions.” Regarding this view that the Constitution was an obstacle to be overcome, not a legitimate charter establishing a system of checks on government power, Wilson never wavered. He complained in 1913 as president: “The Constitution was founded on the law of gravitation. The government was to exist and move by virtue of the efficacy of ‘checks and balances.’ The trouble with the theory is that government is not a machine, but a living thing. No living thing can have its organs offset against each other, as checks, and live.”

Once Wilson decided that America needed to be the world’s policeman (because, again, Wilson knew best), he created the Wilson doctrine that has dominated American politics right up until the Trump presidency (even, in a screwy way, the Obama presidency. I’ve written about it here and won’t repeat myself. It’s enough to say that Wilson used the excuse of war to expand government power beyond anything seen before in America, reaching a point almost equal to martial law.

Wilson’s heir in the 2020 election is Mike Bloomberg. Like Wilson, Bloomberg believes in better living through government micromanagement. He trusts his own judgment about all things is better than the judgment of the American people. He believes that his expertise will make Americans so happy that they won’t notice the loss of their freedoms (especially the Second Amendment). Unlike Wilson, Bloomberg comes out of the business world, not academia, but his approach is the same. Incidentally, despite Bernie’s win in Nevada, creating momentum, don’t count Bloomberg out. Bloomberg believes (probably correctly) that Bernie can’t win. Moreover, he loathes Trump so much that he’ll throw any amount of money at defeating Bernie either before or at the Democrat convention.

As an aside, Adolf Hitler greatly admired Wilson’s approach to governance, including his racial and eugenic policies. After all, once you’ve set yourself up as a bureaucratic, administrative god, you start to see yourself as unconstrained by mere conventional morality.

Eugene V. Debs was a deeply committed socialist and, indeed, was one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World, an international labor union you may remember from your high school history class known as the “Wobblies.” It pretty much tells you everything you need to know about Debs that Howard Zinn greatly admired him: “Debs was what every socialist or anarchist or radical should be: fierce in his convictions, kind and compassionate in his personal relations.”

Bernie Sanders is Debs’ heir in this election. Indeed, Sanders has always been a Debs’ acolyte. In 1979, he made a documentary dedicated to Debs. (The Stanley Kurtz article from which I’m quoting, by the way, is from 2015.)

It’s true that this is a documentary about Debs’s socialism, not Sanders’s. Yet in his 1997 memoir, Outsider in the House, Sanders proudly invokes his Debs documentary and declares that Debs “remains a hero of mine.” Sanders himself plays the voice of Debs in the film. Sanders’ documentary lacks any hint that Debs might have either made mistakes or taken positions that may seem troubling in retrospect. Debs is Bernie’s hero and Bernie clearly wants Debs to be your hero too.

Nowadays, Sanders points to Scandinavian welfare states as the embodiment of his democratic socialism. I don’t doubt that Sanders would like to see America move in that direction, and that is troubling enough. Yet the Debs documentary suggests that Sanders’s ultimate goal lies beyond even European social democracy. The man who made this documentary was pretty clearly a classic socialist: committed to relentless class struggle, complete overthrow of the capitalist system — preferably by the vote, but by violence if necessary — and full worker control of the means of production via the government.

There’s plenty of continuity with Sanders’s current rhetoric here, like his controversial remarks decrying the number of deodorants consumers get to choose from in capitalist society. These days, Sanders calls for a “political revolution,” and the Debs documentary clearly admires labor unions and politicians who seek to bring about revolution by peaceful democratic means. Yet just as clearly, Sanders admires Debs for saying that, in the last resort, violent revolution remains an option.

Sanders’ treatment of Debs’ support for Russia’s communist revolution of 1917 is particularly striking. Here, at least, you might expect a bit of distancing or criticism from a truly “democratic” socialist. Yet Sanders obviously admires Debs’ decision to give “unqualified support to the Russian Revolution which had just taken place under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky.” When Sanders turns to explaining the decline of Debs’ Socialist Party after 1917, he attributes it to the party’s opposition to World War I and to fear of persecution. Nowhere does Sanders suggest that the Russian Revolution and its aftermath may have raised legitimate concerns about socialism. Sanders’s honeymoon in the Soviet Union and his trips to Cuba and Nicaragua make a lot of sense in light of his documentary on Debs.

I recommend reading Kurtz’s entire article. It explains a lot about what Sanders is hiding in this election cycle, especially with his pretense that Denmark, a capitalist state with a strong welfare sector, is what socialism looks like.

Incidentally, I believe that both Buttigieg, the son of an open Marxist college professor, and Amy Klobuchar, a true daughter of leftist Minnesota, hope ultimately to achieve Debs’ goals from 1920. They’re Fabians, though, believing that slo-mo socialism is more palatable than a rush into total socialism.

Warren G. Harding was the establishment favorite. An amiable, corrupt dunce, the Republican party put him in place because they knew they could control him and because his fuzzy politics and his willingness to say whatever it took to win aligned generally with Republican party goals in 1920. Eventually, his corruption caught up with him, ending in the famous (or infamous) Teapot Dome Scandal.

One hundred years later, and the amiable, corrupt dunce is Joe Biden, who entered the primary season as the Democrat establishment’s favorite. Nobody expects much from Joe Biden, other than to just do whatever leftist initiative the backroom boys and girls tell him to do. In the unlikely event he becomes president, his inevitable corruption scandal will easily eclipse anything attached to Harding. Moreover, while Harding may have been a pawn, the Hunter Biden story says that Joe Biden is an actor, not a pawn.

And finally, there’s Teddy Roosevelt. From the first day he hit the American political scene, Teddy Roosevelt was a happy warrior — a truly larger-than-life character. He had a ferocious love for America, was brash and blustery, came up with innovative ideas, and was a fierce warrior against corruption and monopolies. He also had a big, colorful, successful brood, including (by his beautiful first wife) his brilliant, charismatic daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth. He was an American original in every way.

We currently have such an American original in the White House in the person of Donald Trump. He too is a happy warrior — a brash, blustery, larger-than-life character who loves America ferociously and has a big, colorful, successful brood, including (by his beautiful first wife) his brilliant, charismatic daughter, Ivanka Kushner. And Trump, of course, is nothing if not an American original.

Like Trump, who is the most pro-Israel president since 1948, Teddy Roosevelt was deeply philo-Semitic and pro-Zionist:

[T]he president was a profound supporter of Jews and their needs and interests, both at home and overseas, and he was much beloved by the Jewish people. Roosevelt had visited Eretz Yisrael, then under Ottoman rule, in 1873 as a teenager and written about the trip in his diary, including a description of Jews at prayer at the Kotel.

As regimental commander of the famed Rough Riders leading the charge up San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War, he developed great admiration for the bravery of the 17 Jews under his command. Praising them, he said, “One of the best colonels among the regulars who fought beside me was a Jew. One of the commanders of the ship which blockaded the coast so well was a Jew. In my own regiment, I promoted five men from the ranks for valor… and these included one Jew.” The first of the Rough Riders to be killed in action was a Jew, 16-year-old Jacob Wilbusky of Texas (and the first to fall in the American attack on Manila was also a Jew, Sergeant Maurice Joost of California).

As police commissioner, Roosevelt developed a special relationship with Jews, praising them for their dedicated service to New York City. In one celebrated incident, the bravery of a Jewish policeman racing fearlessly into a burning house convinced Roosevelt that Jews could make outstanding contributions to America and that discrimination against them could not be tolerated.

In his autobiography, he tells the amusing tale of a Pastor Hermann Ahlwardt, a German preacher who had embarked on an anti-Semitic crusade against the Jews of New York; Roosevelt specifically assigned 40 Jewish police officers to protect him, writing that the “proper thing to do was to make [Ahlwardt] ridiculous.”

(Do read the whole article from which I quoted because it’s a fascinating look at the last president before Trump who supported Jews and the State of Israel — although Israel was only an idea, not a state, at the time.)

Roosevelt famously believed in speaking softly and carrying a big stick. Trump has changed that a bit. In dealing with America’s enemies, he speaks jovially, even in a very friendly fashion, but he makes clear that he has a big stick. Remember how, while dining with Chinese President Xi, Trump excused himself to order a missile strike on Syria. Trump has also rebuilt the American military, decimated by eight years of Obama policies. Trump makes it clear that he prefers peace but is ready for war.

Naturally, there are differences between Roosevelt and Trump. The most substantive is that Teddy’s crusade against corruption was against corruption in the private sector. Trump, of course, is waging an equally fierce war against corruption within the government itself.

But back to the 1920 campaign season. In 1919, Roosevelt died right as the campaign season began and Wilson was rejected by his own party. In 1920 itself, Debs got less than 4% of the vote, and Harding won.

This time around, things are different: Trump, the Roosevelt cognate, is thankfully not dead but is thriving in the White House. Bloomberg, the Wilson cognate, is falling in the polls. Biden, the Harding cognate, almost certainly won’t win the election because he’s cratering in polls and primaries. And Sanders — the Eugene V. Debs of 2020 — is soaring to wild success in the Democrat primary.

In 1920, American voters did not choose wisely. Harding went on to become one of the least successful, most denigrated presidents in American history. Had he not died in office, leading to Coolidge’s hands-off, constitutional presidency, there’s no telling how far off the rails America might have gone.

Now, in 2020, Americans have another chance to choose wisely. As matters are shaping up, they can hand the presidency to our 21st century Teddy Roosevelt or they can give it to the 21st century Eugene V. Debs. We are being reminded that, while history may line up the same playing pieces, voters do not have to make the same moves.