How should cities cope with the homeless?

Tom Ammiano, San Francisco’s reliably far-Left supervisor, was in the local news today because he’s come out with a new proposal that can be called “the homeless bill of rights“:

Among other things, the proposed law would require legal representation for anyone cited under such laws as San Francisco’s sit/lie law or anti-panhandling ordinance.

It would give “every person in the state, regardless of actual or perceived housing status,” the rights to “use and move freely in public spaces,” to “rest in public spaces,” and to “occupy vehicles, either to rest or use for the purposes of shelter, for 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

However, one provision of the bill can be interpreted to allow restrictions of those activities as long as they are applied equally to all people, and not just homeless people. That leaves wiggle room for evaluation of local ordinances that would probably not spell their immediate dismissal.

(You can see that Ammiano envisions himself as a modern-day Anatole France (“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.”).)

Ammiano’s proposal makes the news in the same week as two other stories about society’s lost souls. The first was the story of Larry DePrimo, the policeman who, frustrated by his inability to aid a barefoot homeless man, went into a shoe store and bought the man a brand new pair of all-weather boots. The second was the story of a crazed man who pushed a father-of-two to his death on the New York subway tracks.

All three stories revolve around a single issue: what should a civilized, affluent society do about those who are too dysfunctional to live a stable life, but are just functional enough to survive on the streets without starving to death?

Any discussion about the homeless has to begin by recognizing that there are two different types of homeless in America. The first type, the one that makes for heart-rending headlines telling us that we must socialize our economy, is the down-on-its-luck family. These families are the economic tragedies, the ones who fell victim to a bad economy and lost first their livelihoods and then their homes. The adults are functional, but have fallen through the cracks, created by bad luck and hard times.

These “working class” homeless are, in theory, quite simple to help. Give them shelter and childcare, and then give mom and dad a job. I understand that the procedure isn’t as easy as the theory. I’m just pointing out that the remedy is a straightforward one, no matter how challenging it may be to implement it.

The second category of homeless people is the more vexing one. These are the ones who are homeless because they have mental diseases or addictions that render them incapable of functioning in normal society under any circumstances. Jeffrey Hillman, who was the beneficiary of Officer DePrimo’s charity, is a prime example (emphasis mine):

It turns out the homeless, barefoot man who captured the hearts of thousands isn’t actually homeless. Jeffrey Hillman, the recipient of a pair of boots given by a good samaritan New York City police officer, has an apartment in the Bronx, officials told the New York Daily News.

According to the Daily News, the 54-year-old Hillman lived in transitional housing sites called “Safe Havens,” from 2009 until 2011. He then secured his current apartment through a Department of Veterans Affairs program that helps homeless vets. Barbara Brancaccio, a spokeswoman for the city agency, told the Daily News that outreach services continue to try and help Hillman, but he “has a history of turning down services.”

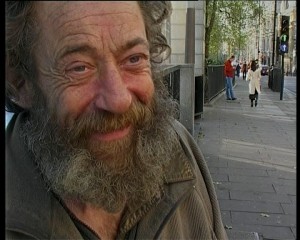

I know Hillman’s type of homeless. You couldn’t miss this type growing up and working in San Francisco. Because San Francisco has a temperate climate, its downtown streets are dotted with filthy men (plus a few women) who sit on the sidewalks all day begging for handouts.

It is immediately apparent looking at these beggars that they are not simply slackers who prefer begging to work. All of them show the signs of serious illness and advanced substance abuse. Many of them are obviously seriously mental ill, with the scariest ones have long, angry conversations with invisible companions.

The paranoid ones, like Hillman, resist help. They would rather live outdoors, even if outdoors means the mean, freezing streets of New York, Chicago, or Boston, than put themselves in one of the shelters that their delusional minds classify as dangerous. To them, having your own primitive tent, cardboard room, or doorway, complete with tinfoil hat and nearby dumpster for food, is a much safer way to live than anything offered by the “enemies” who surround them.

It is these homeless people to whom Ammiano wishes to extend the virtually unlimited right to live on San Francisco’s streets and in her parks. (Incidentally, in San Francisco they live that way already, simply because the City only intermittently enforces its vagrancy laws.) By advancing this right, though, Ammiano manages to forget about the other people in San Francisco, the ones who are not homeless, who work, pay taxes, go to school, play, and otherwise try to live normal lives within the City.

You see, the problem of homelessness isn’t just a problem for the homeless. It’s a problem for everyone. The parks that used to see children playing while their mothers sat nearby in cheerful, chatting clusters quickly turn into needle, condom, feces, vomit, and bottle strewn bogs, complete with smelly, often violent men and women camped out on benches and under bushes. The streets with the charming, inviting stores are now a dirty, smelly mess, repulsing casual shoppers. Tourists, tired of being importuned by by a Calcutta-like stream of beggars, stay away. And because the homeless carry with them lice and tuberculosis, they create public health risks.

More than that, as I’ve frequently argued, it is psychologically damaging to ordinary people in a community to be told that they must allow a person who is manifestly mentally ill, whether because of disease or drugs, to lie around on the streets. I hew libertarian in most respects, but my support for absolute individual freedom begins to fray when an individual is incapable of caring for himself. Just as I wouldn’t say that a five-year old is free to make her own lifestyle choices, I’m loath to allow free rein to a person so mentally ill that he cannot perform basic human functions, such as seeking shelter or feeding himself. To me, he is as incapacitated as a five year old.

The problem is obvious; the solution less so. In the old days, vagrants were thrown into prison, which had the virtue of giving them shelter and food, but also exposed them to criminals who preyed upon them and left them back on the streets when their sentences ended. Another tactic was for the police to tell vagrants to “move along,” getting them off of one cop’s beat and putting them on another’s.

The 20th century saw a growth industry in “modern” psychiatric institutions, which treated the mentally ill as patients rather than as zoo animals, as was the case in old fashioned “insane asylums.” Sadly, though, too many of inmates suffered terrible abuse in these institutions. Because they’re unpleasant work environments, too many employees were lazy and/or sadistic, and too many of the doctors were mini-Mengeles, viewing the mentally ill as human chimps for experimentation.

The 1960s and 1970s, therefore, saw a coming together of the Left and the Right, both of which groups, for different reasons, believed the asylums were dangerous places for society and for the inmates, and passed legislation to close them down. The law of unintended consequences hit hard when these institutions closed: The mentally ill had no place to go but to their families, who either made them crazy in the first place or who couldn’t cope with their craziness, or to the streets.

I don’t have an answer to the question I posed in this post’s title: How should cities cope with the homeless? I know that I disagree strongly with Ammiano’s push to give the homeless a special set of rights that turns San Francisco’s streets into a vast homeless shelter with no recourse for the regular folks who live in and pay for the City. That’s the wrong approach and, to my mind, a cruel one. As humane people, I believe we have a moral obligation to care for those incapable of caring for themselves. The old psychiatric institution model is a good one, because we know that mandatory treatment can work, but I’m at a loss as to how to prevent the abuse that once-upon-a-time made closing these institutions a reasonable decision.

Do you have any ideas?

UPDATE: Welcome, Ace of Spades readers. If you enjoy this post, I invite you to check out the whole site. And if you like what you see, think about subscribing to the Bookworm Room newsletter.