Whatever happened to the idea that dignity is a virtue?

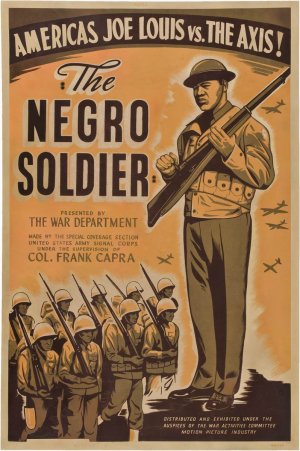

I’m too young to remember a time when dignity was considered a virtue, not only in individuals, but in entire groups. The other night, I was reminded of what I missed when I watched a 1944 U.S. Army Propaganda film, The Negro Soldier, which Frank Capra directed. The Army commissioned the movie because it was trying to reach out to blacks who were unwilling to enlist in the fight.

I’m too young to remember a time when dignity was considered a virtue, not only in individuals, but in entire groups. The other night, I was reminded of what I missed when I watched a 1944 U.S. Army Propaganda film, The Negro Soldier, which Frank Capra directed. The Army commissioned the movie because it was trying to reach out to blacks who were unwilling to enlist in the fight.

The movie qua movie was a resounding success, undoubtedly paving the way for Americans accepting Truman’s executive order integrating the military and, perhaps, moving the American conscience forward towards the Civil Rights movement:

The film began shooting in 1943. The movie crew traveled the United States, visiting over 19 different army posts. The final movie totaled 43 minutes long and received official support in 1944. At first, The Negro Soldier was intended for only African American troops; however, the creators of the film decided that they wanted to distribute the film to a wider military and civil audience. Nobody was certain what the impact of the film would have on viewers, and many people feared that African Americans would have a negative response to the film. However, when the first African American troops saw the film, they insisted that all African American troops should see it. Furthermore, after both African Americans and whites were surveyed about their response to the film, the filmmakers were shocked when over 80% of the white population thought the film should be shown to both black and white troops, as well as white civilians.

Although the Wikipedia article from which I quoted, above, does not say it, TCM stated that blacks did in fact respond to the movie’s message by enlisting in significant numbers. I think you’ll see why if you take the time to watch the movie yourself. Because of it’s importance in American history, the U.S. National Archives restored it and you can see the entire movie here:

The Negro Soldier succeeds in significant part because Carlton Moss, the black man responsible for the script, successfully integrated American blacks into America’s ongoing struggles for freedom and neatly elided the Civil War and its aftermath in the pre-Civil Rights South. The film also showed basic training as a great equalizer, affecting both black and white Americans in the same way.

What struck me so strongly watching the movie 73 years after its release is the way dignity imbues it. The film’s structure is built around a Sunday in a black church. The pastor preaches a sermon explaining how tightly entwined blacks are in America’s historic (and often rough and spotty) for freedom, how Hitler was violently opposed to blacks (with the unspoken message that America might be bad, but a Nazi victory would be worse), and how part of further integrating into the upper echelons of American society requires that blacks step up and engage in America’s war. The members of the congregation to which the pastor preaches are elegantly and classily dressed in their Sunday finest: jackets and ties for men, stoles and hats for women and, of course, service members, both male and female, in their uniforms.

Everyone in the film who speaks, regardless of their accent (northern or southern), speaks a polished, educated English. When a woman reads aloud a letter from her son about boot camp and officer training, her son is manifestly educated and feels that he is a part of “this man’s (and woman’s) army.” While whites might not treat him as an equal — heck, even the Army didn’t treat him as an equal — he knew himself to be an equal, and comported himself appropriately.

The blacks in this movie are dignified, striving people, yearning for education and success. Yes, I know it’s propaganda. But the fact that’s it propaganda actually makes my point. Propaganda’s goal is to reach out to people in the most effective way possible to affect their thinking. In 1944, those who made The Negro Soldier looked at black culture and concluded that the best way to reach out to blacks was to present them, not as hip or cool, not as victims, not as rage-filled revolutionaries, but as people of intellectual and moral substance. Moreover, as I noted above, that approach worked for both blacks and whites who saw the movie.

I find it hard to imagine a filmmaker today using dignity as a means to convey propaganda to American blacks. Madison Avenue, Hollywood, and those blacks who create their own images (Beyonce springs to mind), rely upon entirely different approaches to using media — movies, television, music, newsfotainment — in order to affect their black audiences. Whether these propaganda purveyors are selling products, themselves, or some ideology, the modern approach to blacks runs the gamut all the way from selling sex to foul language to perpetual victimhood to raw anger and race hatred. Here are just a few examples:

The following video comes with a serious content warning:

The following video isn’t as raw and obscene as N.W.A.’s, but if you’re opposed to seeing a woman strut around like the only thing she’s got left to sell is her anger (despite being richer than 99% of the people in America) and her sexuality, you might want to watch only a little of this video too:

Please note that I’m not challenging the messages, whatever the heck they are, in the above videos. I’m challenging the presentation. These fabulously successful black people have concluded that the way to sell their message downstream is not through dignity, decency, moral suasion, facts, or anything else appealing to the higher mind. Instead, they channel their products and messages through a lowest common denominator vulgarity.

For a stunning contrast with a depressing view that sees the commercial world, including the world’s most commercially successful blacks, assume that the only messages that can reach the black community are those steeped in sex, vulgarity, and obscenity, I recommend something I saw on (gasp!) PBS. Accidental Courtesy is a documentary that follows a black musician, Daryl Davis, as he sits down to talk with KKK members, white nationalists, and neo-Nazis, using empathy, politeness, excellent listening skills, humor, and an innate dignity, to reach out to them, man to man (or woman). Davis claims to have led several dozen such people away from their belief system — and has a lot of their clan garments, given to him as spoils of war by their former owners, to prove it. The document is not well-produced and the documentary maker’s inevitable Leftist biases periodically appear, but the show is worth watching to see Davis — to hear his highly humanist, deeply moral, philosophy and to see him in action. (You can watch the documentary at the above link through February 28.)

Showing once again how out of time I am — that is, how poorly I mesh with our current culture — I think it’s a great loss to America generally and to American blacks specifically that dignity is a forgotten virtue. Dignity lifts people up. It means that, when people treat you badly, this bad conduct reflects solely on them. You are not humiliated because your own dignity raises you above their bad behavior. As Martin Luther King, Jr., showed, dignity is both a sword and a shield.

Having said that, let me end on a slightly silly note. There’s a scene from Singing In The Rain, that always pops into my head when I hear the word “dignity.” In it, the first scene in the movie, the great silent movie star Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) gives a highly sanitized version of his rise to fame along with his friend Cosmo Brown (Donald O’Connor). He opens by boasting that the motto by which they live is “Dignity, always Dignity.” As with so many Hollywood stories, this good-natured movie shows that this narrative is a lie: