Trump’s judicial choices, regulations, and cleaning up dog poop

What better way to explain how regulations are barriers to access than to talk about disposing of dog poop? And thank goodness for Trump’s judicial picks.

Let me begin by clarifying what I will not say in this post: I will not say that Trump’s judicial choices are the equivalent of dog poop. I have liked his judicial choices and consider them the equivalent of cleaning up dog poop. It’s regulations — and the bureaucracy that enforces them — that are like cleaning up dog poop.

Let me begin by clarifying what I will not say in this post: I will not say that Trump’s judicial choices are the equivalent of dog poop. I have liked his judicial choices and consider them the equivalent of cleaning up dog poop. It’s regulations — and the bureaucracy that enforces them — that are like cleaning up dog poop.

I’m not explaining this well. Let me begin with the dog poop.

I have dogs and a back yard (for my English readers, a “back garden”). Although I take my dogs for exercise walks around the neighborhood, the backyard is the repository for their business. I actually take them back there myself, because we’ve never been able to make the yard sufficiently dog proof to keep them from roaming. Add in the fact that people have found coyotes in their yards in my neighborhood and that raptors bigger than my dogs routinely circle overhead, and you can see why I’m with them every step of the way.

Although my yard is spacious, and my dogs small, the poop accumulates surprisingly fast. When you’re with your dogs every step of the way, having poop landmines scattered about is stressful and, if I’m not paying attention, quite unpleasant. For years, whenever the poopmines overwhelmed me, I’ve laboriously worked my way through the grass and weeds searching for doggie gifts, which I’ve deposited in a big bag, ready to go into the garbage.

It would have made a lot more sense over the years if I’d behaved in my yard the same way I behave on my neighborhood walks: Have a poop bag on hand, clean up the poops immediately, and then immediately dispose of them in a garbage can. (And our suburban neighborhood very nicely has poop bags and garbage cans available at regular intervals in popular dog-walking areas.) It’s that last part, though, the putting the collected poop in a garbage can, that has stopped me.

Here’s the thing: The way my lot is configured, to get from yard to garbage, I have to open a six-foot-tall, quite warped wooden fence, with the latch at the very top (for code reasons). Since I’m only five-feet-tall, this would be challenging under the best of circumstances. Add in a damaged shoulder, and you’ll understand why I really dislike grappling with that fence. It’s always been easier for me to let the poop accumulate so that I deal with that fence only infrequently.

Some of you may already have figured out the solution to this problem but I’m a bit slow and, after almost two decades, I finally figured it out last week: I bought a small, covered bin for the yard that’s just for poop. I now have clean-up bags that I take with me every time I walk with the dogs in the yard. I clean up after them at the source (defusing instantly those poop-mines), and then toss the bags into the covered bin. Only when that bin is full will I have to grapple with that darn fence. My yard is a lovelier place now and I am happy.

What I did, of course, was remove a barrier to access.

Barriers to access are amazing things. If we truly want to do something (or just want something), we successfully ignore them. Putting a child safety latch on the freezer door has never deterred me from getting ice cream. Likewise, in public areas, landscape architects who have crafted beautiful curving paths through a lush green lawn have watched in horror as people hurrying from point A to point B invariably ignore the path and cut a straight line across the grass. Here’s a nice photograph demonstrating a “desire path,” as it’s called:

On the other hand, if there’s a barrier to something that’s not a matter of pressing urgency or desire — a fence between me and routinely cleaning up dog poop — that barrier might as well be an impenetrable brick wall.

And now, having droned on about dog poop and access barriers, I am finally ready to talk about Trump’s judicial choices. According to the New York Times, Trump has one overriding goal when selecting lower court judges. He wants men and women who want to restore a constitutional judiciary by clawing back judicial power from un-elected administrative law judges:

The Trump administration has a new litmus test: reining in what conservatives call “the administrative state.”

With surprising frankness, the White House has laid out a plan to fill the courts with judges devoted to a legal doctrine that challenges the broad power federal agencies have to interpret laws and enforce regulations, often without being subject to judicial oversight. Those not on board with this agenda, the White House has said, are unlikely to be nominated by President Trump.

The criteria were first used last year in his Supreme Court selection of Neil M. Gorsuch, an appeals court judge who became something of a hero on the right for chastising his fellow jurists for being too deferential to government functionaries. And antipathy to regulations has been a factor in the selection of the dozens of judicial nominations since then.

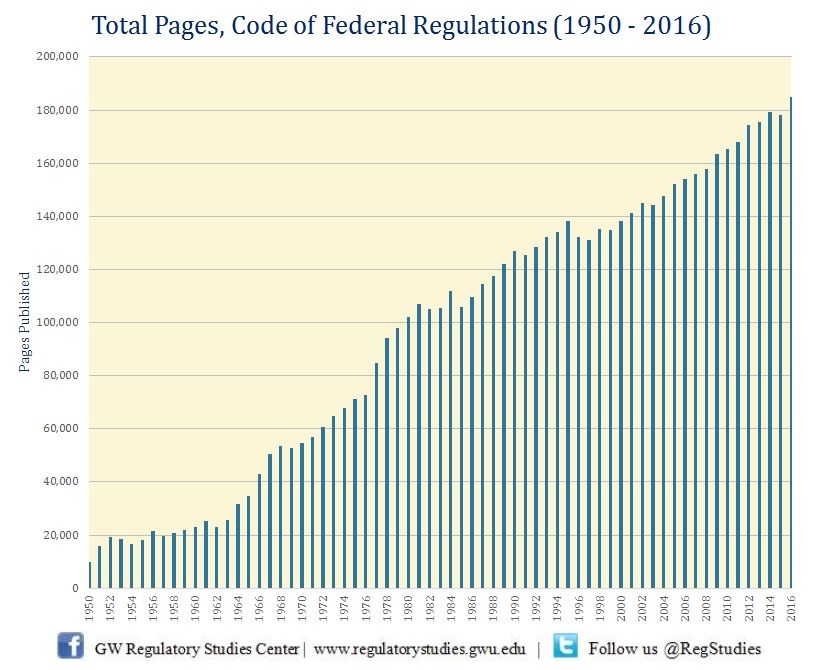

What administrative law judges do, of course, is enforce regulations. Thousands of thousands of regulations. This chart shows how, between 1950 and the last year of the Obama administration, the Code of Federal Regulations expanded from around 10,000 pages (which is still too many) to over 180,000 pages. (And please note the sudden spike in Obama’s last year in office.)

Every one of those regulations is a barrier imposed against someone or something: against a manufacturer, an employer, an employee, a citizen, and even the government itself.

Please understand that I’m not entirely anti-regulation. I would never demand that we do away with all of them. I’m glad that factories are safer than they were at the end of the 19th century. I like it that there are minimal regulations preventing pharmacies from feeding children antifreeze to sweeten medicines or ensuring that our milk isn’t polluted with melamine (great for unbreakable plates; bad for consumption).

Living as I do in earthquake country, I don’t think local building codes requiring structural integrity are inappropriate. Without those codes, you end up with earthquake destruction that looks like Mexico City in 1985:

On the other hand, when we were thinking of building a mother-in-law cottage behind our house, I balked when I was told that the interior had to be ADA complaint, even thought it was being built on our private property and no one (yet) needed an ADA compliant living or working space. The requirements would have added significantly to the cost of building and, because I wasn’t enthused about the project anyway, I said “no.” I saved money, but a potential contractor and all of his employees lost a business opportunity. The perfect proved to be an expensive enemy of the good.

For someone with a brilliant idea but little money, or a person with an intriguing idea but caught in a rut, onerous regulations will be an effective barrier to their innovation and entrepreneurship. Again, these examples are of local regulations, not federal, but just think about how states demand that people have licenses to braid hair or arrange flowers.

At the state level, regulations are often intended to protect an entrenched monopoly. At the federal level, though, these regulatory barriers serve multiple purposes: pushing policies (EPA), protecting people (OSHA), deliberately destroying industries (coal?), or simply keeping a bureaucracy’s wheels humming and its bureaucrats employed. Some regulations are useful, but so many are not. And as I mentioned above, there’s always the “perfect is the enemy of the good” problem. Take a persnickety regulation and hand it to a dogmatic or grumpy inspector, and a whole factory can grind to a halt because a walkway is a quarter-inch too narrow, something that does not affect functionality or safety, or an employee hung a picture five inches too low in a hallway.

Trump understands that our regulatory state is completely out of control. It has become the equivalent of a huge wall between the dog poop and the garbage can. It stifles the economy. It destroys initiative. And it places unparalleled power in the hands of people who have managed to bypass completely our democratic process. We, the People, are supposed to have a say in the representatives who pass the laws that affect us. That say does not exist in a bureaucratic state.

Anything that Trump does to remove unnecessary barriers is a wonderful thing — and appointing judges who understand this is a way to ensure the reining in of the decidedly undemocratic regulatory state.